|

Word Gems

exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Editor's 1-Minute Essay:

What, Why, How:

Writing That's Worth Reading

return to "Writing" main-page

Henry David Thoreau: "Books are the treasured wealth of the world …Their authors are a natural and irresistible aristocracy in every society, and, more than kings or emperors, exert an influence on mankind."

it's about having something worthwhile to say

Most writers try to impress with attempts at being clever, or outrageous, or iconoclastic. They say more than they know, and take a long time saying it. Others, equally vacuous, "high-fiving" each other all around, will then praise this banality as "great writing." Kinda gets ya right here.

But F. Scott Fitzgerald and Matthew Arnold, I think, hit it dead on -- a writer must have something to say. If you have something to say, something important to say - a rare commodity, it's true - then it hardly matters how you say it, as the world, eventually, will demand to hear it.

And I can hear you ask, how shall I have something important and worthwhile to say? Ahh, now we're talking.

cures what ails you

The royal road to wisdom cannot be so easily quantified and set to formula as elixir. We can't put it in a bottle and sell it for $29.95. However, there is one method that will help us on our way.

the hundred-book program

I taught my children this principle when they were very young. Choose a topic that speaks to your passion. If you read 100 books on this subject - 300 would be better - along with ensuing meditation and digestion over many years, a day will come when you will know more about this subject than 99% of all others in the world.

Meditation and reflection will be your daily workshop. Allow the treasure-trove of inductive process, the gathered research, to percolate and simmer in your head. You will find, in a "cross-fertilization of ideas," that gold-nuggets of knowledge, acquired by reading and experience, will begin to mix-and-match in all manner of creative, insightful union.

Editor’s note: Dr. Amit Goswami asserts that creativity is a “quantum” process. It’s a “discontinuous jump” -- the famous "quantum leap" -- from the known all the way, as "The Wedding Song" has it, to “something never seen before.” How shall the gap be spanned? By a combination of “doing” and “being,” he says. The “doing” part is your inductive fact-gathering, and the “being” part is that of allowing the “quantum possibilities” to simply manifest and drop into your head. The great insights won't come by "trying very hard to think" but, rather, by shutting down the incessant chattering of the "monkey mind." You can write without muting "the voice in the head," but it won't be great, it won't be remembered, it won't move people where they live. It's destined for the circular-file.

And, after many years of this meditative work, in these inspired combinations, blessed by the creative muse, you will begin to walk farther, see things more clearly, know things more deeply, in your chosen subject, than few in the world, or in history, have ever seen or known. And then you must joyously tell the world of your findings.

It's called good writing. But it's much more than that.

We should not strive to become "good writers" so much as "good thinkers" and "good persons," because only the virtuous will ever gaze upon the higher levels of truth.

Writing is the easy part. Good writing, of the enduring sort -- not of Bartholomew’s wry "[we can] hardly get to the wastebasket in time” -- will become an extension of one's very life-force, one's "soul energies." Yes, good writing is the easy part, the mere communication, a reporting to the world of one's unique and valuable discoveries, sometimes requiring many years of intellectual and spiritual labor.

In this vein, Einstein famously stated, "It's not that I'm so smart, but that I stay with problems longer."

Do you love your field of enquiry so much as to unceremoniously work alone, undeified, investing solitary years and even decades, pursuing it, all the way to wondrous clarity?

Writing, properly framed, should be seen as part of the truth-seeking process. To say that someone is a “good writer,” without having something worthwhile to write, is like saying a carpenter is a “good nail-pounder” when the new house is uninspiring or defective. We don’t care if the nail-pounding or the writing is “good” if the content, the end-product, sucks.

Listen to Einstein on the issue of long-suffering regarding a project:

“The final results [of his work on the theory of relativity] appear almost simple; any intelligent undergraduate can understand them without much trouble. But the years of searching in the dark for a truth that one feels, but cannot express; the intense effort and the alternations of confidence and misgiving, until one breaks through to clarity and understanding, are only known to him who has himself experienced them.”

how few in the history of the world have ever experienced the thrill of clarity

There are extremely few joys in life comparable to that of "breaking through to clarity," having sedulously sought for it over much time. At the end of this process, one not only apprehends a beginning answer -- because all answers are tentative pending further light -- but mentally witnesses a thousand factoids dancing in formation, the detritus of investigation, all marching toward that final clarity. Simply reading about it in a text-book, noting the work of others, as Einstein referenced the "undergraduate," could never compare.

When your topic is worthy, and when you know it as intimately as this, you will become a "good writer," in a natural way, almost as an afterthought. Then, just let it flow; as Rilke said, having waited "for the birth," let it flow, a self-manifestation, now issuing with the joyful exuberance of a child.

Why will you be joyful? Because in that moment of long yearned-for clarity, you will have briefly glimpsed an aspect of reality, possibly, never seen before; a previously undiscovered particle of the mind of God. In all the world, this joy is second only to "what we stay alive for."

Editor’s note: And don’t confuse “good writing” with monetary success. Don’t let the unenlightened, the “rabble in the marketplace,” define who you are or what “the truth” should be. They will merchandize you for their own egoic purposes, and then cast you aside as a spent cartridge. So many of the most accomplished in history, in all fields, were rejected and despised by the smart-money. You must believe in yourself and the inner whisperings of truth that guide you. Consider, anew, the wise words of Viktor Frankl, now applied to the subject of good writing:

it must ensue

“Don't aim at success. The more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side effect of one's personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself... Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it... listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge. Then you will live to see that in the long-run—in the long-run, I say!—success will follow you precisely because you had forgotten to think about it.”

|

how to begin writing

“To know what you’re going to draw,” instructs Picasso, “you have to begin drawing.”

So it is with writing. When the creative muse taps your shoulder and whispers, “it’s time”; when clarity finally summons; when you sense that, "ah, at last, I have something to say"; then – how to begin? The answer is, simply begin.

Writing will now pour from you in a natural way. As you write, all the world, and you yourself, will discover exactly what it is you have to say.

|

the substitute-teacher

Many years ago, while seeking for a teaching job in my home state of North Dakota – which effort proved unsuccessful as local politics barred my entrance – I found myself as a substitute-teacher for the day, addressing an English class, a group of high school seniors, only weeks from graduation. I had no prepared material or lecture to deliver. They’d never seen me before, and I did not know them, and, I could tell by their expressions, they expected our short time together to be of a “filler” nature.

Surveying my captive audience, I sat on one of the desks at the head of the room, which expression of nonchalance, I’m sure, only augmented the class's perceptions of low expectation: we hate the imposed fire-side chat. However, after brief introduction, I now asked them a pert question:

“Would you like to learn, during the next five minutes, how to become a great writer? It’s simple to explain.”

Well, they were polite and voiced no disbelief, but demeanor and eyes-of-doubt revealed an incredulity; and rightly so. But then, continuing, I added:

“I didn’t say it was simple to do, but only simple to explain.”

I proceeded to offer the information in the above paragraphs. After some minutes, many of these students felt the magic-stardust power of these precepts. My wish for them, and for you, is that you might touch, and live in, the wonder of these things.

|

creative insight is a function of 'no mind' rather than 'more mind'

Over the last twenty years, readers have sometimes praised my writings. I’m seen, by some, as a “deep thinker,” which, they assume, must be so to have constructed Word Gems with its panoply of insights into mysteries.

While I appreciate a good word now and then, I must protest against excessive encomium. It’s not realistic. It's not true. Whatever I see can be seen by anyone who will take the time to access the inner person. No one has a corner on the truth, everyone will be taught directly by Spirit, if we allow it.

Ascribing a status of “deep thinker” misconstrues the process. Creative insight is a function of “no mind” rather than “more mind.” Applying this principle to the craft of writing, let me say that there is no such thing as “writer’s block.” When we sense that the “creative muse” is absent, it’s best to go on to something else and simply wait to be “inspired.” If a writer attempts to write when he or she has nothing to say, I guarantee that it will come out wrong.

I experience this process every day. I may have recently finished some new article or inset-box and every time, when I do, a little voice or feeling in my head gives the same speech:

“Well, that writing is done. I guess it was ok, it could have been better, but maybe I did offer at least a little something that was new and helpful. But, you’re all done, buddy. I think you got lucky. Wherever that last insight came from, it’s over, and you’re a dry well now. You know it wasn’t ‘you’ that produced it, and so don’t think that you can make lightning strike again. You’re not going to have any more insights because it’s just not in you.”

I experience this soliloquy just about every day. And so, when it comes, I almost believe it, because that’s how I really feel. I do feel like a dry well. I don’t feel like a “thinker” at all. I feel like I’m still the same glassy-eyed kid in high school who has no idea what's going on; especially, in a certain area of life.

And so I'm all done. I move on to some other activity. I free my mind. I don’t “try very hard” to be creative. Quite the opposite. I just leave it. I relax. And then, maybe that same day, or the next day, I’m listening to a song, or watching a movie, or driving, or reading something, or I see something in nature – and then an insight, bang!, “coming out of nowhere,” hits me, and I say to myself, with intensity and almost a breathless quality, “I have to write about this and share it with others.” And then we’re off to the races one more time -- the very last time, I’m certain.

See the article on "Higher Creativity."

|

|

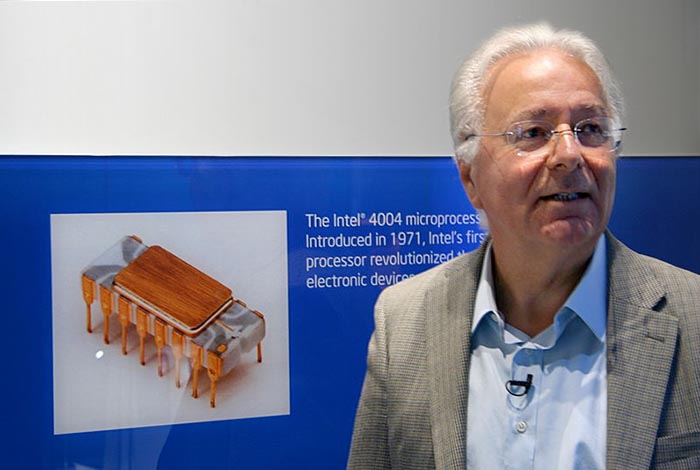

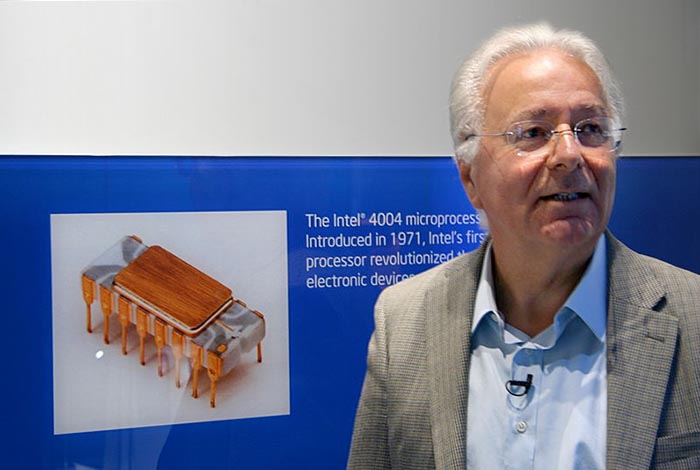

Frederico Faggin, inventor of the first silicon chip in 1971, says that writing for him is a kind of meditation, a discipline, as it allows a “parsing”, a refining , as he says, of thoughts.

"Writing is the combination of rationality and experience... a work of love toward myself and the world."

see the interview at 2:09

|

what will we write about when there are no threats and the world no longer needs saving

|

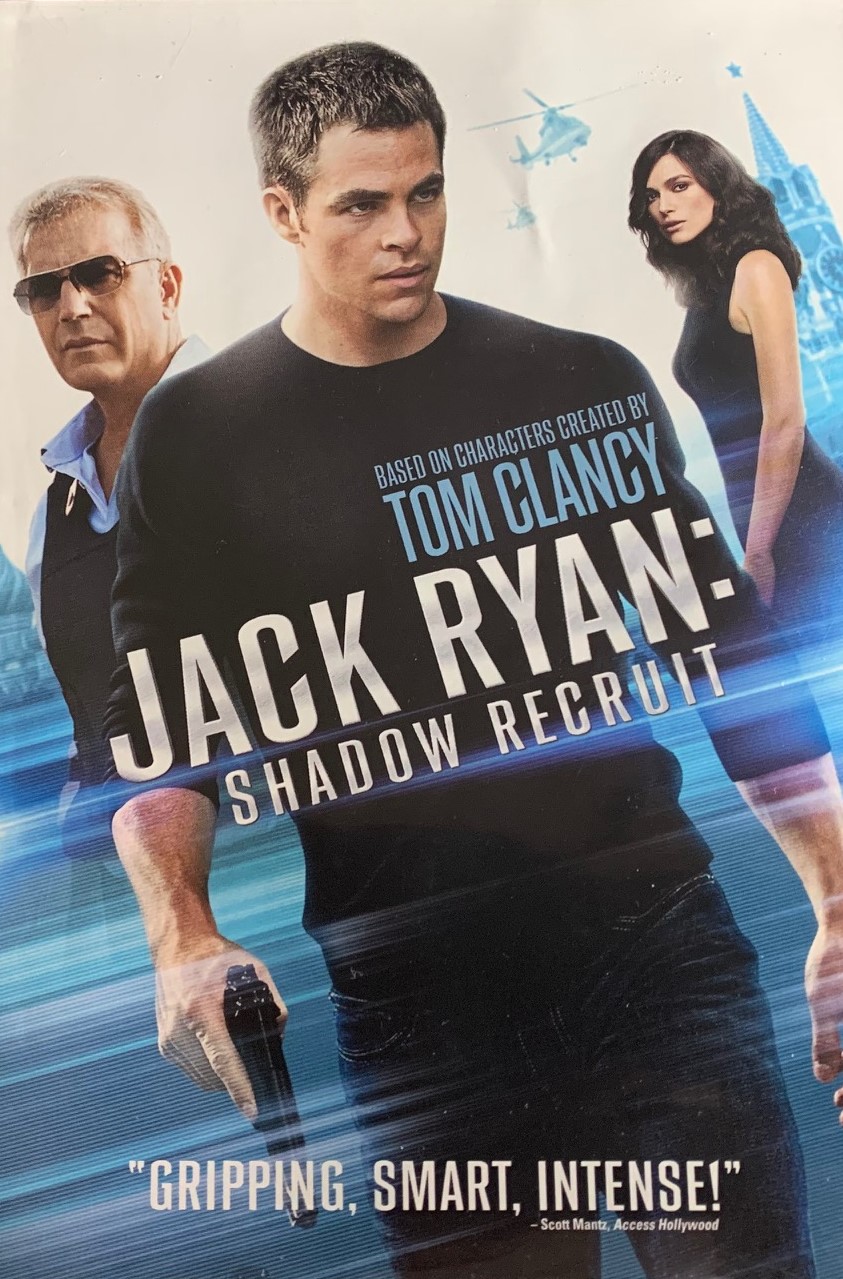

Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit (2014)

Dr. Jack Ryan (Chris Pine) and Dr. Cathy Muller (Keira Knightley)

Editor’s note: The great writers, as we’ve seen, assert that a “story” is defined by some form of problem-cause-solution. Think about it; pretty much every plot or narrative in any movie or novel features some threat by a grasping ego - and this is what we call a "story." If it doesn't have the element of threat to be overcome, then it's not a "story."

But what will happen in Summerland, a perfect society, where there are no threats, no invasions, no wars, nothing to mar and jar? Will there still be such a thing as writing or storytelling? Will the "story" survive the next world?

Kairissi. We spoke of Jack and Cathy in “the 500” writing, but they can help us again to think about the author’s question.

Elenchus. In our world, people wish for heroes to thwart those who would destroy civilization. But will Jack and Cathy be out of business in Summerland?

K. In a sense, yes, as Summerland cannot be invaded or threatened. But this does not mean that people in Summerland do not work for the greater good.

E. Granted, but will this service toward humankind make for a “good story,” as the great writers like to define it?

K. I would have to say, no.

E. It’s interesting. The definition of “story” and “drama” has unfolded over time, especially since the fifth century BC when the Greeks invented “tragedy.” And, some decades later, Aristotle, in his Poetics, attempted to set a standard for a good drama. He said that it needed to have “reversal, recognition, and suffering.”

K. Explain this to us.

E. There needs to be a “reversal” of the story’s action. Things are going one way, everything’s fine, or not fine, but then things change for some unexpected reason.

K. We see this "reversal" all the time in movies and novels.

E. And then there’s “recognition.” The audience thinks it has a certain character all figured out, but then he or she suddenly is revealed as something else.

K. That's unnerving, but it's a common element in literature.

E. “Suffering” is self-explanatory. The characters in a drama are burdened with calamity.

K. I think Aristotle was right. And these three elements are very commonly used in almost all dramas today. But, even so, it leaves me with a rather empty feeling. Yes, all the calamity creates interest – about as interesting as a train wreck.

E. So, does this mean there’ll be no stories in Summerland?

K. I think storytelling and writing will be led to higher ground.

E. Ok, let me play devil’s advocate to bring a good answer to this. In the Jack Ryan movie, we see people performing heroic deeds to stop the bad guys. In that sense, it’s a typical action movie with a lot of slam-crash-boom all around. Many of the people involved, good and bad, are killed and things get broken. But this chaos couldn’t happen in Summerland, and so, would the “story” still be interesting?

K. Here’s the deal. In our world, problem-cause-solution stories, generally speaking, are written by dysfunctional egos for an audience of dysfunctional egos. The ego craves to strengthen its sense of “me against them,” a sense of isolation and “otherness.” The typical action movie, or any other movie featuring traits of the ego, is just red meat to the “needy little me.” It just loves it. It feels stronger with all the dramatic "otherness."

E. Ok, so what you’re really saying is that Summerland is a place inhabited by people who are beginning to live from the “true” rather than the “false self.”

K. When this happens, one’s choice of art and entertainment will change, too.

E. In “the 500” writing we used the phrase “It’s the joy, stupid.” We said that Jack Ryan did what he did for the honor and joy of serving, as opposed to bolstering a “needy little me.”

K. In Summerland, this elevation of spirit will be “writ large” upon society. We’ll no longer be so impressed or fascinated by “slam-crash-boom” or by drama's "three elements."

E. Good point. Why would we want to watch a movie about “threats to the world” when one’s world cannot be threatened by any means whatsoever.

K. In that day, we will seek out artists, philosophers, the wise, the able, the prescient, who can reveal a higher level of joy, a clearer vista of beauty, a more sublime inspiration -- and show us how to attain these. Coming to a theatre near you, buddy.

E. Could we sit alone way in the back of the theatre?

K. (small smile)

while standing in line at the bank...

During a trip to my local bank, as I chatted with the teller while he processed my transaction, our brief conversation turned toward the downloading of free apps concerning virus protection. I suggested that it’s always safest to go to a reputable service-provider’s home site and retrieve the app from that safe territory rather than downloading it from some random ad, which might be fishing for your information, and not to your benefit.

With this last comment, a lady standing behind me in line, overhearing the banter, couldn’t help herself but to interject, “Oh, really? I didn’t know that! That sounds like good advice with all the scams on the internet these days.”

Later, her exclamatory remark came to mind as I prepared this inset-box on “story-telling as problem-cause-solution.” It occurred to me that the lady had found my “story” extremely interesting, so much so that she couldn’t contain herself but to know more. And why? Was her engrossed curiosity fanned by just the right words and clever phrases, just the right delivery, from me? Of course, it was none of that. In a hot moment, she’d found herself gripped by fears of invasion of privacy, of identity theft, and the like.

And I submit to you that, virtually, 100% of the time, that which passes for a “great story” in our world is just the Needy Ego reveling in either its terrors of loss or its cravings for “more.”

How could this checkered dynamic hope to survive in a perfected world of Summerland? While it will take time for us to shed our worst nightmares of neediness when we cross over, eventually, as we mature, as we start to believe that everything is truly alright now, in sated well-being, with no threats of any kind extant, we will find ourselves unimpressed with the typical problem-cause-solution story format of our troubled world. It won't cut it for us anymore.

This coming elevated frame of mind will change the very foundational underpinnings of what is considered to be art. In that new day of loftier perspective, we'll be asking, “Who can show me a clearer example of ‘the joy’? of beauty? of loftier perspective? Who can be my mentor to attain greater happiness? Who can help me access even a particle more of the mind of God? That’s what I care about now.”

|

|

we don’t like stories that have 'no ending,' that leave us 'hanging,' with no resolution of plot and no clear statement of good and evil

In the early 1960s, on cold winter evenings, Dad would watch a television program, “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.”

I was just a young kid and didn’t really care for it too much – too cerebral, not enough action. But, I still recall, more than once, at the end of these programs, Dad virtually cursing the tv with “that made no sense,” or “there was no ending,” or “how are we supposed to know what happened?”

We don’t like stories like that; in fact, according to the great writers, if you create some writing like this, it’s not even to be classified as a “story.”

Stories have endings; stories tell you the good from the bad; stories might not have a pleasant conclusion, but at least they need to wrap things up so we can say “been there, done that, got the video and the t-shirt.” If it doesn’t do that, it’s not even a “story” – we don’t know what it is, but it’s not a “story.”

Well, Hitchcock may have been a little ahead of his time. In his own way, he attempted to portray “art as reflecting nature”; for, if we're older than seven, we may have noticed that Life rarely ties up circumstances with a pretty pink bow and a cherry on top. Most of what happens on planet Earth leaves us hanging, events go unresolved, good and evil often drift into a grey zone, with loose ends and unfinished business everywhere.

|

If one is caught in a hurricane at street level, all seems as chaos, utter confusion, and disorder. However, from outer space, a higher perspective, that same chaos becomes cosmos – a breathtakingly beautiful swirl of order, a purposeful orchestration of symmetry and proportion.

|

the popular concept of “story,” with its structured problem-cause-solution outline, is part of the larger dysfunctional ego’s craving for control and safety, for order and system, and, at a deeper level, reflects its terror of living in this unpredictable and dangerous world

There's nothing wrong with liking a story with a happy ending and justice served; we'd all like that for ourselves. However, if we crave and insist on a certain literary structure to assuage our terrors of living life, then it can become pathological. It's the "canary in the coal mine" that signals trouble for us. What kind of trouble? - a systemic spiritual blindness and love for illusion.

Editor's note: Compare the ego's craving for "order and system" to the definition of cultism.

The ego wants to eliminate uncertainty and clearly label everything as “good” or “bad”; thereby, it believes, gaining a measure of power over the randomness of life. Its problem in this effort, however, is that it has no idea what “good” or “bad” really means.

Eckhart Tolle helps us to understand.

an excerpt from Eckhart Tolle's "New Earth"

CHAOS AND HIGHER ORDER

When you know yourself only through content, you will also think you know what is good or bad for you. You differentiate between events that are “good for me” and those that are “bad.” This is a fragmented perception of the wholeness of life in which everything is interconnected, in which every event has its necessary place and function within the totality. The totality, however, is more than the surface appearance of things, more than the sum total of its parts, more than whatever your life or the world contains.

Behind the sometimes seemingly random or even chaotic succession of events in our lives as well as in the world lies concealed the unfolding of a higher order and purpose. This is beautifully expressed in the Zen saying “The snow falls, each flake in its appropriate place.” We can never understand this higher order through thinking about it because whatever we think about is content; whereas, the higher order emanates from the formless realm of consciousness, from universal intelligence. But we can glimpse it, and more than that, align ourselves with it, which means be conscious participants in the unfolding of that higher purpose.

When we go into a forest that has not been interfered with by man, our thinking mind will see only disorder and chaos all around us. It won't even be able to differentiate between life (good) and death (bad) anymore since everywhere new life grows out of rotting and decaying matter. Only if we are still enough inside and the noise of thinking subsides can we become aware that there is a hidden harmony here, a sacredness, a higher order in which everything has its perfect place and could not be other than what it is and the way it is.

The mind is comfortable in a landscaped park because it has been planned through thought; it has not grown organically. There is an order here that the mind can understand. In the forest, there is an incomprehensible order that to the mind looks like chaos. It is beyond the mental categories of good and bad. You cannot understand it through thought, but you can sense it when you let go of thought, become still and alert, and don't try to understand or explain. Only then can you be aware of the sacredness of the forest.

As soon as you sense that hidden harmony, that sacredness, you realize you are not separate from it, and when you realize that, you become a conscious participant in it. In this way, nature can help you become realigned with the wholeness of life.

GOOD AND BAD

At some point in their lives, most people become aware that there is not only birth, growth, success, good health, pleasure, and winning, but also loss, failure, sickness, old age, decay, pain and death. Conventionally these are labeled “good” and “bad,” order and disorder. The “meaning” of people's lives is usually associated with what they term the “good,” but the good is continually threatened by collapse, breakdown, disorder; threatened by meaninglessness and the “bad,” when explanations fail and life ceases to make sense.

Sooner or later, disorder will erupt into everyone's life no matter how many insurance policies he or she has. It may come in the form of loss or accident, sickness, disability, old age, death. However, the eruption of disorder into a person's life, and the resultant collapse of a mentally defined meaning, can become the opening into a higher order.

“The wisdom of this world is folly with God,” says the Bible. What is the wisdom of this world? The movement of thought, and meaning that is defined exclusively by thought. Thinking isolates a situation or event and calls it good or bad, as if it had a separate existence. Through excessive reliance on thinking, reality becomes fragmented. This fragmentation is an illusion, but it seems very real while you are trapped in it. And yet the universe is an indivisible whole in which all things are interconnected, in which nothing exists in isolation. The deeper interconnectedness of all things and events implies that the mental labels of “good” and bad” are ultimately illusory. They always imply a limited perspective and so are true only relatively and temporarily.

This is illustrated in the story of a wise man who won an expensive car in a lottery. His family and friends were very happy for him and came to celebrate. “Isn't it great!” they said. “You are so lucky.” The man smiled and said “Maybe.” For a few weeks he enjoyed driving the car. Then one day a drunken driver crashed into his new car at an intersection and he ended up in the hospital, with multiple injuries. His family and friends came to see him and said, “That was really unfortunate. “Again the man smiled and said, “Maybe.” While he was still in the hospital, one night there was a landslide and his house fell into the sea. Again his friends came the next day and said, “Weren't you lucky to have been here in hospital.” Again he said, “Maybe.”

The wise man's “maybe” signifies a refusal to judge anything that happens. Instead of judging what is, he accepts it and so enters into conscious alignment with the higher order. He knows that often it is impossible for the mind to understand what place or purpose a seemingly random event has in the tapestry of the whole. But there are no random events, nor are there events or things that exist by and for themselves, in isolation. The atoms that make up your body were once forged inside stars, and the causes of even the smallest event are virtually infinite and connected with the whole in incomprehensible ways. If you wanted to trace back the cause of any event, you would have to go back all the way to the beginning of creation. The cosmos is not chaotic. The very word cosmos means order. But this is not an order the human mind can ever comprehend, although it can sometimes glimpse it.

NOT MINDING WHAT HAPPENS

J. Krishnamurti, the great Indian philosopher and spiritual teacher, spoke and traveled almost continuously all over the world for more than fifty years attempting to convey through words, which are content – that which is beyond words, beyond content.

At one of his talks in the later part of his life, he surprised his audience by asking, “Do you want to know my secret?” Everyone became very alert. Many people in the audience had been coming to listen to him for twenty or thirty years and still failed to grasp the essence of his teaching. Finally, after all these years, the master would give them the key to understanding. “This is my secret,” he said. “I don't mind what happens.”

He did not elaborate, and so I suspect most of his audience were even more perplexed than before. The implications of this simple statement, however, are profound. When I don't mind what happens, what does that imply? It implies that internally I am in alignment with what happens. “What happens,” of course, refers to the "suchness" of this moment, which always already is as it is. It refers to content, the form that this moment – the only moment there ever is – takes. To be in alignment with what is means to be in a relationship of inner nonresistance with what happens. It means not to label it mentally as good or bad, but to let it be.

Does this mean you can no longer take action to bring about change in your life? On the contrary, when the basis for your actions is inner alignment with the present moment, your actions become empowered by the intelligence of Life itself...

|

Kairissi. Ellus, may I offer just a quick word in summary concerning this discussion of "story"?

Elenchus. Please, Dear.

K. It’s so uncanny. All of our lives we’ve known the common word “story” and, subliminally, I guess, have always seen it to be something as solid and stable as the sun in the sky. But now it’s revealed as just one more guise of the ego.

E. It is somewhat incredible. We thought we knew what “story” means.

K. I guess what really bothers me is that, like the author’s dad, we don’t like stories that “have no ending.” And that sense of unease should have tipped us off to a hidden disquietude down below. We want stories to be all wrapped up with a bow because the ego doesn’t like all this uncertainty and unpredictability of mortal existence.

E. But it gets worse - then we find out that reality, at its core quantum underpinnings – as explained by Heisenberg – is not built on cut-and-dried cause-and-effect but is probabilistic in nature.

K. That frightenes most of us. We want stories to be like children’s fairy tales where everything is resolved, evil is controlled, the good guys always win, finalized with a proper "The End". And Summerland is something like that. But, at least for our world, Alfred Hitchcock was the better prophet.

K. I was thinking about your comment on Aristotle’s “three elements of tragedy.” And I couldn’t help but think of us in that context.

E. (silence)

K. “Recognition”: that was our problem for a long time. We didn’t know, or we knew but wouldn’t admit, who we are to each other.

E. (silence)

K. “Reversal”: It takes my breath away to realize the delight, brief as it was, that we experienced in those earliest years - that was a happy time for us; but then we traded it for “Suffering.”

E. We learned from William Aber, the trance-medium, that the Guides actually keep Twins apart in the early years, lest they come together too soon, and lose their opportunity to learn by suffering.

K. Ellus, it’s almost as if God and the Guides are cosmic dramatists, employing effective stagecraft technique to create a compelling story.

E. I have to admit, sometimes I’ve wondered, our story is so fraught with the “three elements,” so infused with every facet of human interest, that…

K. (sighing) … that, maybe, someday, our story will become somewhat known on the other side.

E. A textbook case exhibiting all that Twins should not do?

K. I don’t know, Ellus. I think you’re making a little joke with that. I think we did about as well as we could, given our level of immaturity. And I think it just might be possible that what we went through will someday become encouragement to others who must travel the same road.

so, tell me again, just what is good writing

Let's review the comment by Ernest Hemingway:

|

as an artist becomes famous, the sacred creativity process, which brought him to the fore, is often abandoned, resulting in a production of the banal

Ernest Hemingway, acceptance speech, 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature (excerpt):

"Things may not be immediately discernible in what a man writes, and, in this, sometimes he is fortunate; but, eventually, they are quite clear, and by these and the degree of alchemy that he possesses, he will endure or be forgotten.

"Writing, at its best, is a lonely life…[the writer] grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and [then] often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone, and, if he is a good enough writer, he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day."

Gellhorn and Hemingway

Editor’s note: We understand Hemingway’s warning. How often we have seen artists, in various fields of endeavor, rise meteorically in public acclaim due to outstanding work, but then falling victim to the siren song, with a forgetting of how he or she got there. In times past, I would ask, "Why aren't they still producing the great songs, the great books, the great paintings?" Hemingway explains it to us.

the perdition of venality

Once you’re doing well enough to land the Oprah interview, or the mega book-deal advance, or the stadiums jammed with screaming fans, chances are - you’re on the way down. The muse gasps and sputters for its breath of life. You begin to believe the propaganda of the fickle mob gushing what a genius you are. Elitism ossifies the heart. You start to rely on innate ability, mere talent; you're not "listening" anymore, as Isaiah did. The early workshop of haunting introspection, the laboring alone in the dark, the quest to express an image of beauty that is sensed but not articulated, is summarily abandoned; bright lights and applause now distract and dull the mind - and the rules of higher creativity are shunted to the side.

the creeping self-damnation

You might still produce art, but not worthy of the term; and, for a time, the egoic crowd, seeking to identify with a "hero," will scramble for it; but - you, yourself, with great disdain, will understand, too well - it won’t be great art, it won’t be long remembered, it won’t represent "facing eternity,” as per Hemingway.

It is the perdition of venality, the unremitting torment of lost, once-creative, souls.

Paul Johnson, Intellectuals: "...Hemingway's awareness of his inability to recapture his genius, let alone develop it, accelerated the spinning circle of depression and drink. He was a man killed by his art, and his life holds a lesson all intellectuals need to learn: that art is not enough."

|

He says that the good writer works alone. Why does he work alone? He works alone because his source of artistry comes from within; as Emerson said, “Man is his own star,” his own source of light and truth.

If the writer is any good, says Hemingway, every day he or she “must face eternity.” What does this mean “face eternity”? It means that the writer must seek for the grand truth of life, love, and all reality.

And, having glimpsed these ineffables, the writer must now share the vision with the world. This is what good writing is.

Is it any wonder that the life of the authentic writer is a lonely life? Very few will accept this as a calling. If it is accepted, and done so honestly, heroically, selflessly, one will not, however, truly be alone but will live in the near-constant influence of both a Higher Power and Spirit Guides who will be “opening the eyes” to that wider view of reality.

postscript

The following was presented on the "Clear Thinking" page but well addresses the issue of the story without final ending:

|

Editor's last word:

Alexander the Great, personally tutored by Aristotle, sophisticated enough to conquer the world, could not rise above his own version of “local nomos.”

Will Durant comments: Alexander "remained to the last a slave to superstition… before the battle of Arbela he spent the night performing magic ceremonies." Can we transcend our own cultural programming, the little voice in the head, that seeks to mute and scuttle rationality?

The Queen of Hearts, with her studied and practiced belief in impossible things, represents society’s fear of uncertainty. This results in an indoctrination of children concerning "the right answer" which, with a wink, we call education.

But there is no true education in “believing” anything, no true education in planting flags, memorizing and repeating the "right answer," but only that open mind which allows one to follow the evidence, faithfully and honestly, toward more refined, ordered, and closely-approximating perceptions of reality. Welcome to our quantum universe of probabilistic answers.

F. Scott Fitzgerald explains it to us

Helping children to stand on their own, to face unafraid the ambiguities of clear thinking, is a requirement of a life well lived. While we wait for more data to offer crisper definitions of "the truth," we must purposefully endure any cognitive dissonance, courageously accept incomplete, tentative, or seemingly paradoxical answers.

we are cautioned against worshipping the idol of certainty

Those who do engage in such worship, like Peter Pan, remain perpetual children.

This is what Fitzgerald is warning about. People are frightened of living with uncertainty. We want solid and firm answers. We want to “believe” and proclaim that we’re “right.” And it’s this neurotic desire for immediate absolute knowledge that drives us into the cults, in various forms - totalitarian politics, materialistic science, 'infallible' religion, one-answer academia, the greed-led corporate world.

|

more than drinking the koolaid

The long reach of cultism encompasses much more than crackpot churches. The root idea of cult offers the sense of "cut." This core concept of "cut" leads us to images of refinement and refashioning and, by extension, development, control, pattern, order, and system.

Cultism as systemization finds a ready home in religion and philosophy which seek to regulate and redistill the patterning and ordering of ideas. However, in a larger sense, the spirit of cultism extends to every facet of society. We find it scheming and sedulously at work in politics, academia, family, corporations, entertainment, science, artistry – anywhere power might be gained by capturing credulous and fear-based minds.

See the “cultism” page for a full discussion.

|

Instead, we must grow up, put away childish fears, and acknowledge that living with uncertainty, to a degree, will always be with us. It’s unavoidable. Reality itself, quantum-based, is founded upon uncertainty. There’s no escaping it.

nature is not at war with itself, there are no real contradictions, but only our incomplete perceptions

As Fitzgerald puts it, we must be willing to entertain seemingly contradictory information. Of necessity, this sense of the incomplete is inescapable because we will always possess only part of the truth, and, until we come into more complete views, a perception of “opposed ideas” will confront us.

But this dichotomy is only apparent, not real. Nature, in fact, is a coherent, interlaced whole and is not at war with itself; there are no real contradictions, no real paradoxes, once we perceive a larger picture. Niels Bohr was on the right track with his "complementarity principle."

try to offer one example, from all of history, where uncertainty has been totally defeated, where 'happily ever after' continued undisturbed

We can't do it because absolute "certainty" does not exist in the external 3-D world.

To begin to achieve this enhanced "totality," this larger view of "certainty", demands a maturity as product of "going within"; it requires an abandoning of childish fears seeking for fairy-tale conclusions of "certainty", all loose ends wrapped up neatly with a definitive "the end"; moreover, in practical terms, it becomes a refusal to run to the cults and their Dear Leaders who offer “certainty.”

In the history of the world, there has never been an altogether conclusive "the end" to anything - but fearful children ever seek for this comfort.

the mark of a first-rate intelligence

Answers will always be incomplete because (1) there's a universe filled with knowledge out there, to say nothing of the fact that (2) the five senses systemically fall victim to illusion. We must face the reality that we deal not only with incomplete data but imperfect means of accessing. The mind's "content" suffers diminshment on both fronts.

More than "content" we must also address "structure." We are to embrace Bruce Lee's sentiment, the “quietly alive, aware and alert”, ready-for-anything, mental life of a free man or woman - free of the ego, without identifying with "strong father" symbols, offering faux certainty of "infallible laws", absolutist pronouncements, or final-word solutions - none of these exist in Nature, in an evolving, quantum universe.

The primary existential issue is that of "structure," not "content," as avenue to greater sentience; in other words, more information, more content for the mind, per se, will not make us feel safe and secure but only an altering of "structure," an upward shifting of consciousness.

This is what’s most important, this is the foundational mindset of the truth-seeking mature individual - this is the mark of a first-rate intelligence.

|

Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

Earth's crammed with Heaven

And every common bush afire with God

But only he who sees takes off his shoes

|