|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

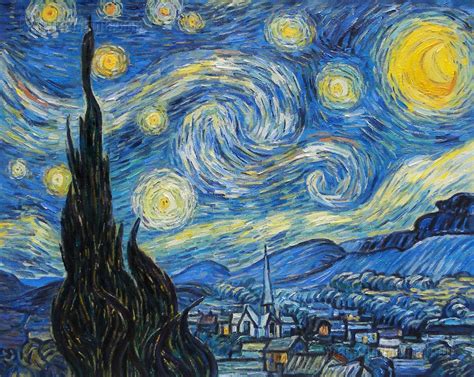

How To Sit Quietly Vincent van Gogh:

To answer Vincent’s question, I would offer: Not quite the only one, but nearly so.

Recently I was listening to a university professor’s taped lecture on an aspect of ancient history. He was knowledgeable, articulate, and presented his material well. However, I suddenly found myself dismayed as this man of letters lapsed into a casual insult, a fashionable bigotry, as if one were addressing an unthinking beast; that of, ridiculing rural America as a preserve of the unsophisticated, a dearth of anything worth the time of a cultured person. And I thought of Vincent van Gogh’s statement regarding seeing “eternity” built into the prairie’s endless horizon. What the learned professor failed to understand is that a flat landscape is what it is – a tabula rasa, a blank canvas, if you will – and we, from the storehouse of our own hearts, supply either the sense of “there’s nothing there” or an enchanted view of eternity’s unbounded marvel. Editor’s note: Vincent’s quotation affected me deeply in another way. Actually, I sort of gasped as I read it because, in my own way, I have tried to convey the very same perception of the bucolic mystical. See the Word Gems homepage, the paragraphs under the heading, “I’ve Become The Prairie,” my own glimpse of eternity - “apotheosis: an inexhaustible capacity; no discernible limit to human potential; expansive horizon, as far as the eye can see, and beyond.”

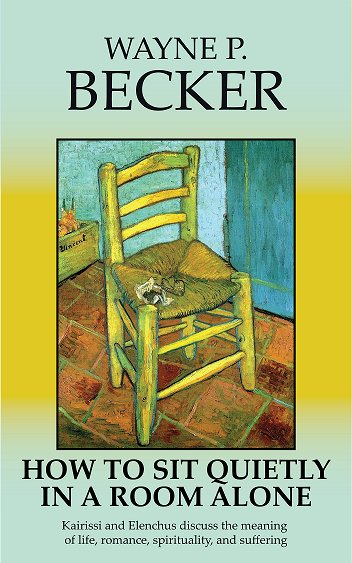

I’d always heard that van Gogh was crazy, cut off his own ear, that sort of thing. But I should have known better than to rely on the local gossip. As I’d chosen Vincent’s famous artwork of the forlorn chair as symbolism of my “quiet room” project...

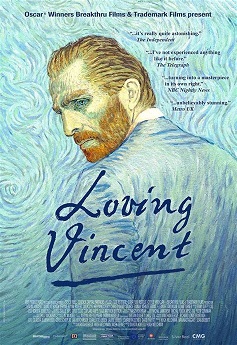

... I thought it best to say a few words about the painter. At my local library, the attendant, responding to my request for information, pressed upon me, “Oh, you need to see this documentary, and this one, and this one.” More than I wanted to know, I thought. But how wrong I was, on many counts, concerning the work and life of this most misunderstood artist, this great soul. I heartily recommend these DVDs. Each is wonderful in its own right.

Willem Dafoe does a great job in a docu-drama of van Gogh's working years. And "Loving Vincent" is truly amazing. It's an animation, but not a cheap cartoon. And get this: over 100 artists worked on this project, producing -- it's hard to describe! -- a flowing, detailed, visual effect created in the style of Van Gogh's own impressionistic artistry! It's both beautiful and uniquely phenomenal. but virtually none of the story was what I was expecting

There’s much that might be discussed here, but it’s best that I focus on my particular purpose; the DVDs are a good source for a full review of van Gogh’s life. This acknowledged, very briefly, I would like to tersely comment on main points of misunderstanding as this confusion relates directly to the thesis of this book.

what about his time in the insane asylum I doubt that he needed to be there. Here’s what happened. Vincent didn’t want to be in a big city like Paris, though his dear brother Theo lived there. He liked to be out in nature as this is where he found his inspiration. And so he moved to a village in the south of France. Every day, the townspeople would see Vincent hike out into the countryside to find something to paint. But they didn’t understand him. They thought he was odd and treated him like the proverbial “village idiot” – even though Vincent was very well educated, spoke four languages, and read Shakespeare for fun. The children in the village started taunting him, and then began to throw rocks at him. They would not have done this without support from mom and dad. At one point, having been pelted with rocks, Vincent ran after the young culprit and grabbed him, confronted him, just outside the boy’s house, where the latter "played the victim." The shouting drew the parents and the neighbors to the scene, and Vincent was accused of abusing the child, whereupon he suffered physical injury from the mob. After this, he voluntarily agreed to spend time in an asylum, a refuge from the hostilities. In a letter to his brother, he confided, though he remained a whole year in the safe-house, he did so because the rent was cheap and living was easier than in the village. He could paint there unmolested. He especially loved painting at night, when eternity came into crisper view.

Did he not cut off his own ear? Regarding the famous severed ear incident, I had always thought this to be a simple case of self-mutilation by a psychotic. But, no, there’s more to it. Some churches, especially in the past, have taken a literal stance toward Jesus’ metaphoric instruction, “If your hand offend you, cut it off,” or “If your eye offend you, gouge it out.” Vincent had been schooled in the Gospels by a stern minister-father. During a time of great sorrow, upon hearing the news that he’d been rejected by a close friend, Vincent decided to remove the offending ear. Was this an action of a balanced mind? Not exactly as I submit to you that people around you, people that you know and consider to be "sane," surrender to and believe similar anti-humanistic religious doctrines which, if put to scrutiny, would fare about as well as "if your ear offend you."

but did not his insanity lead to suicide After reviewing the conflicting reports surrounding his death, I feel that Vincent van Gogh did not commit suicide. Two of the DVDs deal with this issue, "Eternity," but especially, "Loving Vincent." The evidence strongly suggests that he was accidentally shot in the stomach by a couple of fellows who were roughhousing with a loaded pistol. He was quietly painting, as usual, they were interrupting his peace, and were rude to him. In their buffoonery, the gun went off, and Vincent went down.

today, he'd be on anti-depressants and have a normal life More than half of the people in your city draw strength from some form of tranquilizer or anti-depressant. This is not unusual. Vincent did suffer from mood swings and low-spirits. But, it appears that this condition could have been managed with better medical treatment.

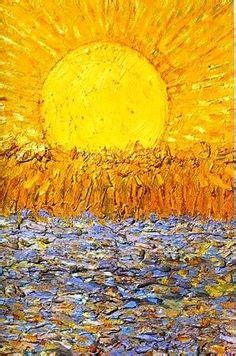

the 900 letters Why do I suggest that, essentially, Vincent was not unusually mentally stressed? I say this because, in fact, we know a lot about Vincent van Gogh. Almost every day he would write to his brother Theo. Nine hundred letters survive, and in these missives Vincent reveals himself. Yes, at times he felt very stressed, even out of control, but then, being treated as a village idiot might put a crimp in anyone’s day. But, far more than references to stress, Vincent speaks as an enlightened person. The documentaries often allude to the letters, and very frequently Vincent is found to be soaring to heights of ecstasy in terms of some aspect of nature’s beauty that he’s discovered. Moreover, as the great soul, often he says things like, “Oh, how I want people to see what I see! Oh, how I want them to know the beauty that I know! How I want the world to feel alive as I feel alive!”

the meaning of the explosively bright colors Vincent van Gogh is called the father of modern art. He put impressionistic artwork firmly on the map. In so doing, he invented a new style, one of vibrant, riotous, swirling, unapologizing colors. This was his way of saying to the whole world, “Oh, how I wish you could feel what I feel when I see the beauty of nature, when I see eternity in everything! These bright colors are my way of saying that I am in love with life and wish so much for you to be as well.”

an open field, a flat landscape, the unbounded horizon, as “quiet, small room” Sometimes, if the whole world is mad and won’t let you be, then you might need to go out into nature to find a “quiet, small room” in which to be alone. This is what Vincent did every day - communing with creation and with his own deeper self, the life within.

|

||||

|

|