|

Word Gems

exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

How To Sit Quietly

In A Room Alone

Thoreau’s Walden Pond as

“Quiet Room” of Transformation

return to the "contents" page

To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust.

|

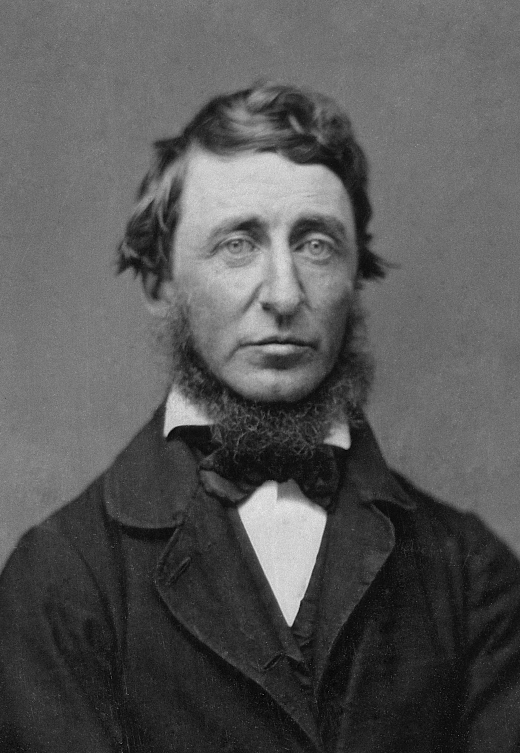

Henry David Thoreau

1817-1862

Every human being, without exception, making one’s way through the initial stages of enlightenment, will begin to sense a certain antipathy with the ways of this materialistic world.

The distance will become palpable. The old allurements are now perceived as vulgarities, a dehumanizing sleep-walking. And there will be a rising up, from an uncharted center, of desire for authentic living.

This process of inner awakening, the soul coming of age, is presented to us in Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. His two year, two month seclusion in a modest cabin with pond became, for the Concord sage, a veritable small-and-quiet room of transformation.

|

Editor’s note: I’ve provided excerpts from Walden which, in my opinion, feature Thoreau’s growing perspicacity and sensitivity toward life and living.

CHAPTER 1

the misfortune of having inherited a farm; soon it will own you

I see young men, my townsmen, whose misfortune it is to have

inherited farms, houses, barns, cattle, and farming tools; for these

are more easily acquired than got rid of. Better if they had been

born in the open pasture and suckled by a wolf, that they might have

seen with clearer eyes what field they were called to labor in. Who

made them serfs of the soil? Why should they eat their sixty acres,

when man is condemned to eat only his peck of dirt? Why should they

begin digging their graves as soon as they are born? They have got

to live a man's life, pushing all these things before them, and get

on as well as they can. How many a poor immortal soul have I met

well-nigh crushed and smothered under its load, creeping down the

road of life, pushing before it a barn seventy-five feet by forty,

its Augean stables never cleansed, and one hundred acres of land,

tillage, mowing, pasture, and woodlot! The portionless, who

struggle with no such unnecessary inherited encumbrances, find it

labor enough to subdue and cultivate a few cubic feet of flesh.

But men labor under a mistake. The better part of the man is

soon plowed into the soil for compost. By a seeming fate, commonly

called necessity, they are employed, as it says in an old book,

laying up treasures which moth and rust will corrupt and thieves

break through and steal. It is a fool's life, as they will find

when they get to the end of it, if not before.

what a man thinks of himself indicates his fate

How godlike, how immortal, is he? See how he cowers

and sneaks, how vaguely all the day he fears, not being immortal nor

divine, but the slave and prisoner of his own opinion of himself, a

fame won by his own deeds. Public opinion is a weak tyrant compared

with our own private opinion. What a man thinks of himself, that it

is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate.

Self-emancipation even in the West Indian provinces of the fancy and

imagination -- what Wilberforce is there to bring that about?

Think, also, of the ladies of the land weaving toilet cushions

against the last day, not to betray too green an interest in their

fates! As if you could kill time without injuring eternity.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called

resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you

go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the

bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious

despair is concealed even under what are called the games and

amusements of mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes

after work. But it is a characteristic of wisdom not to do

desperate things…

they think they have no choice

Yet they honestly think there is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that the sun rose clear. It is never too late to give up

our prejudices. No way of thinking or doing, however ancient, can

be trusted without proof.

what my neighbors call good, I believe to be bad

The greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my

soul to be bad, and if I repent of anything, it is very likely to be

my good behavior. What demon possessed me that I behaved so well?

You may say the wisest thing you can, old man -- you who have lived

seventy years, not without honor of a kind -- I hear an irresistible

voice which invites me away from all that. One generation abandons

the enterprises of another like stranded vessels.

All change is a miracle to contemplate; but it is a miracle which is taking place every instant. Confucius said, "To know that we know what we know, and that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge."

With respect to luxuries and comforts, the wisest have ever lived a more simple and meagre life than the poor. The ancient philosophers, Chinese, Hindoo, Persian, and Greek, were a class than which none has been poorer in outward riches, none so rich in inward. We know not much about them. It is remarkable that we know so much of them as we do. The same is true of the more modern reformers and benefactors of their race. None can be an impartial or wise observer of human life but from the vantage ground of what we should call voluntary poverty.

there are professors of philosophy but almost none are philosophers, "lovers of wisdom"; they know about but do not know

There are nowadays professors of philosophy, but not

philosophers. Yet it is admirable to profess because it was once

admirable to live. To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle

thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to

live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence,

magnanimity, and trust. It is to solve some of the problems of

life, not only theoretically, but practically. The success of great

scholars and thinkers is commonly a courtier-like success, not

kingly, not manly. They make shift to live merely by conformity,

practically as their fathers did, and are in no sense the progenitors of a noble race of men.

No man ever stood the lower in my estimation for having a

patch in his clothes; yet I am sure that there is greater anxiety,

commonly, to have fashionable, or at least clean and unpatched

clothes, than to have a sound conscience.

I would rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself than be crowded on a velvet cushion. I would rather ride on earth in an ox cart, with a free circulation, than go to heaven in the fancy car of an excursion train and breathe a malaria all the way.

Who bolsters you? Are you one of the ninety-seven

who fail, or the three who succeed? Answer me these questions, and

then perhaps I may look at your bawbles and find them ornamental.

The cart before the horse is neither beautiful nor useful. Before

we can adorn our houses with beautiful objects the walls must be

stripped, and our lives must be stripped, and beautiful housekeeping

and beautiful living be laid for a foundation: now, a taste for the

beautiful is most cultivated out of doors, where there is no house

and no housekeeper.

Near the end of March, 1845, I borrowed an axe and went down to

the woods by Walden Pond, nearest to where I intended to build my

house, and began to cut down some tall, arrowy white pines, still in

their youth, for timber. It is difficult to begin without borrowing, but perhaps it is the most generous course thus to permit your fellow-men to have an interest in your enterprise. The owner of the axe, as he released his hold on it, said that it was the apple of his eye; but I returned it sharper than I received it.

I began to occupy my house on the 4th of July, as soon as it was boarded and roofed, for the boards were carefully feather-edged and lapped, so that it was perfectly impervious to rain, but before boarding I laid the foundation of a chimney at one end, bringing two cartloads of stones up the hill from the pond in my arms. I built the chimney after my hoeing in the fall, before a fire became necessary for warmth, doing my

cooking in the meanwhile out of doors on the ground, early in the

morning: which mode I still think is in some respects more

convenient and agreeable than the usual one. When it stormed before

my bread was baked, I fixed a few boards over the fire, and sat

under them to watch my loaf, and passed some pleasant hours in that

way. In those days, when my hands were much employed, I read but

little, but the least scraps of paper which lay on the ground, my

holder, or tablecloth, afforded me as much entertainment, in fact

answered the same purpose as the Iliad.

The most interesting dwellings in this country, as the

painter knows, are the most unpretending, humble log huts and

cottages of the poor commonly; it is the life of the inhabitants

whose shells they are, and not any peculiarity in their surfaces

merely, which makes them picturesque; and equally interesting will

be the citizen's suburban box, when his life shall be as simple and

as agreeable to the imagination, and there is as little straining

after effect in the style of his dwelling.

The religion and civilization which are barbaric and heathenish build splendid temples... Most of the stone a nation hammers goes toward its tomb only. It buries itself alive. As for the Pyramids, there is nothing to wonder at in them so much as the fact that so many men could be found degraded enough to spend their lives constructing a tomb for some ambitious booby, whom it would have been wiser and manlier to have drowned in the Nile, and then given his body to the dogs. I might possibly invent some excuse for them and him, but I have no time for it. As for the religion and love of art of the builders, it is much the same all

the world over, whether the building be an Egyptian temple or the

United States Bank. It costs more than it comes to. The mainspring

is vanity…

each should pursue his own way, and not his father's or his mother's

One young man of my acquaintance, who has inherited some acres,

told me that he thought he should live as I did, if he had the

means. I would not have any one adopt my mode of living on any

account; for, beside that before he has fairly learned it I may have

found out another for myself, I desire that there may be as many

different persons in the world as possible; but I would have each

one be very careful to find out and pursue his own way, and not his

father's or his mother's or his neighbor's instead.

goodness tainted

There is no odor so bad as that which arises from goodness

tainted. It is human, it is divine, carrion. If I knew for a

certainty that a man was coming to my house with the conscious

design of doing me good, I should run for my life…

Editor's note: Concerning this "goodness tainted," the cloaked designs of avarice, see excerpts of Adrian Smith's essay "The Mask of Piety" on the "Authority" page.

Be sure that you give the poor the aid they most need, though it

be your example which leaves them far behind. If you give money,

spend yourself with it, and do not merely abandon it to them. We

make curious mistakes sometimes. Often the poor man is not so cold

and hungry as he is dirty and ragged and gross. It is partly his

taste, and not merely his misfortune. If you give him money, he

will perhaps buy more rags with it.

There are a thousand hacking at the branches of

evil to one who is striking at the root, and it may be that he who

bestows the largest amount of time and money on the needy is doing

the most by his mode of life to produce that misery which he strives

in vain to relieve.

CHAPTER 2

a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can

afford to let alone.

The nearest that I came to actual possession was when I bought the Hollowell place, and had begun to sort my seeds, and collected materials with which to make a wheelbarrow to carry it on or off with; but before the owner gave me a deed of it, his wife -- every man has such a wife -- changed her mind and wished to keep it, and he offered me ten dollars to release him. Now, to speak the truth, I had but ten cents in the world, and it surpassed my arithmetic to tell, if I was that man who had ten

cents, or who had a farm, or ten dollars, or all together. However,

I let him keep the ten dollars and the farm too, for I had carried

it far enough; or rather, to be generous, I sold him the farm for

just what I gave for it, and, as he was not a rich man, made him a

present of ten dollars, and still had my ten cents, and seeds, and

materials for a wheelbarrow left.

When first I took up my abode in the woods, that is, began to

spend my nights as well as days there, which, by accident, was on

Independence Day, or the Fourth of July, 1845, my house was not

finished for winter, but was merely a defence against the rain,

without plastering or chimney, the walls being of rough,

weather-stained boards, with wide chinks, which made it cool at

night.

Every morning was a cheerful invitation to make my life of equal

simplicity, and I may say innocence, with Nature herself. I have

been as sincere a worshipper of Aurora as the Greeks. I got up

early and bathed in the pond; that was a religious exercise, and one

of the best things which I did. They say that characters were

engraven on the bathing tub of King Tchingthang to this effect:

"Renew thyself completely each day; do it again, and again, and

forever again." I can understand that. Morning brings back the

heroic ages. I was as much affected by the faint hum of a mosquito

making its invisible and unimaginable tour through my apartment at

earliest dawn, when I was sitting with door and windows open, as I

could be by any trumpet that ever sang of fame.

The morning, which is the most memorable season of the day, is the awakening hour. Then there is least somnolence in us; and for an hour, at least, some part of us awakes which slumbers all the rest of the day and night. Little is to be expected of that day, if it can be called a day, to which we are not awakened by our Genius

The Vedas say, "All intelligences awake with the morning." Poetry and

art, and the fairest and most memorable of the actions of men, date

from such an hour… Morning is when I am awake and there

is a dawn in me.

how few are awake to the divine life

The millions are awake enough for physical labor; but

only one in a million is awake enough for effective intellectual

exertion, only one in a hundred millions to a poetic or divine life.

To be awake is to be alive. I have never yet met a man who was

quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?

We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by

mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which

does not forsake us in our soundest sleep. I know of no more

encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate

his life by a conscious endeavor. It is something to be able to

paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a

few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and

paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which

morally we can do.

I wish to live deliberately

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to

front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn

what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I

had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is

so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite

necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of

life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all

that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive

life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it

proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world

simplicity, simplicity, simplicity

Our life is frittered away by detail. An honest man has hardly need

to count more than his ten fingers, or in extreme cases he may add

his ten toes, and lump the rest. Simplicity, simplicity,

simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a

hundred or a thousand; instead of a million count half a dozen, and

keep your accounts on your thumb-nail. In the midst of this

chopping sea of civilized life, such are the clouds and storms and

quicksands and thousand-and-one items to be allowed for, that a man

has to live, if he would not founder and go to the bottom and not

make his port at all, by dead reckoning, and he must be a great

calculator indeed who succeeds.

simplify, simplify

Simplify, simplify. Instead of three meals a day, if it be necessary eat but one; instead of a hundred dishes, five; and reduce other things in proportion. Our life is like a German Confederacy, made up of petty states, with its boundary forever fluctuating, so that even a German cannot tell you how it is bounded at any moment. The nation itself, with all its so-called internal improvements, which, by the way are all external and superficial, is just such an unwieldy and overgrown

establishment, cluttered with furniture and tripped up by its own

traps, ruined by luxury and heedless expense, by want of calculation

and a worthy aim, as the million households in the land; and the

only cure for it, as for them, is in a rigid economy, a stern and

more than Spartan simplicity of life and elevation of purpose. It

lives too fast. Men think that it is essential that the Nation have

commerce, and export ice, and talk through a telegraph, and ride

thirty miles an hour, without a doubt, whether they do or not; but

whether we should live like baboons or like men, is a little

uncertain.

If we do not get out sleepers, and forge rails, and

devote days and nights to the work, but go to tinkering upon our

lives to improve them, who will build railroads? And if railroads

are not built, how shall we get to heaven in season? But if we stay

at home and mind our business, who will want railroads? We do not

ride on the railroad; it rides upon us.

Why should we live with such hurry and waste of life? We are

determined to be starved before we are hungry. Men say that a

stitch in time saves nine, and so they take a thousand stitches

today to save nine tomorrow. As for work, we haven't any of any

consequence. We have the Saint Vitus' dance, and cannot possibly

keep our heads still.

For my part, I could easily do without the post-office. I think

that there are very few important communications made through it.

To speak critically, I never received more than one or two letters

in my life -- I wrote this some years ago -- that were worth the

postage. The penny-post is, commonly, an institution through which

you seriously offer a man that penny for his thoughts which is so

often safely offered in jest. And I am sure that I never read any

memorable news in a newspaper. If we read of one man robbed, or

murdered, or killed by accident, or one house burned, or one vessel

wrecked, or one steamboat blown up, or one cow run over on the

Western Railroad, or one mad dog killed, or one lot of grasshoppers

in the winter -- we never need read of another.

I perceive that we inhabitants of New England live this

mean life that we do because our vision does not penetrate the

surface of things. We think that that is which appears to be.

spend one day as deliberately as Nature

Let us spend one day as deliberately as Nature, and not be

thrown off the track by every nutshell and mosquito's wing that

falls on the rails. Let us rise early and fast, or break fast,

gently and without perturbation; let company come and let company

go, let the bells ring and the children cry -- determined to make a

day of it… If the bell rings, why should we run? We will consider what kind of music they are like.

Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward

through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition,

and delusion, and appearance, that alluvion which covers the globe,

through Paris and London, through New York and Boston and Concord,

through Church and State, through poetry and philosophy and

religion, till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we

can call reality…

Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in. I drink at it; but

while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is.

Its thin current slides away, but eternity remains. I would drink

deeper; fish in the sky, whose bottom is pebbly with stars. I

cannot count one. I know not the first letter of the alphabet. I

have always been regretting that I was not as wise as the day I was

born. The intellect is a cleaver; it discerns and rifts its way

into the secret of things. I do not wish to be any more busy with

my hands than is necessary. My head is hands and feet. I feel all

my best faculties concentrated in it.

CHAPTER 3

With a little more deliberation in the choice of their pursuits,

all men would perhaps become essentially students and observers, for

certainly their nature and destiny are interesting to all alike. In

accumulating property for ourselves or our posterity, in founding a

family or a state, or acquiring fame even, we are mortal; but in

dealing with truth we are immortal, and need fear no change nor

accident.

books are the treasured wealth of the world, authors a natural and irresistible aristocracy

Books are the treasured wealth of the world and the fit inheritance of generations and nations. Books, the oldest and the best, stand naturally and rightfully on the shelves of every cottage. They have no cause of their own to plead, but while they enlighten and sustain the reader his common sense will not refuse them. Their authors are a natural and

irresistible aristocracy in every society, and, more than kings or

emperors, exert an influence on mankind.

Those who have not learned to read the ancient classics in the

language in which they were written must have a very imperfect

knowledge of the history of the human race … for later writers, say

what we will of their genius, have rarely, if ever, equalled the

elaborate beauty and finish and the lifelong and heroic literary

labors of the ancients. They only talk of forgetting them who never

knew them. It will be soon enough to forget them when we have the

learning and the genius which will enable us to attend to and

appreciate them. That age will be rich indeed when those relics

which we call Classics, and the still older and more than classic

but even less known Scriptures of the nations, shall have still

further accumulated, when the Vaticans shall be filled with Vedas

and Zendavestas and Bibles, with Homers and Dantes and Shakespeares, and all the centuries to come shall have successively deposited their trophies in the forum of the world. By such a pile we may hope to scale heaven at last.

only a poet can read poetry

The works of the great poets have never yet been read by

mankind, for only great poets can read them. They have only been

read as the multitude read the stars, at most astrologically, not

astronomically. Most men have learned to read to serve a paltry

convenience, as they have learned to cipher in order to keep

accounts and not be cheated in trade; but of reading as a noble

intellectual exercise they know little or nothing; yet this only is

reading, in a high sense, not that which lulls us as a luxury and

suffers the nobler faculties to sleep the while, but what we have to

stand on tip-toe to read and devote our most alert and wakeful hours

to.

I think that having learned our letters we should read the best

that is in literature, and not be forever repeating our a-b-c's, and

words of one syllable, in the fourth or fifth classes, sitting on

the lowest and foremost form all our lives. Most men are satisfied

if they read or hear read, and perchance have been convicted by the

wisdom of one good book, the Bible, and for the rest of their lives

vegetate and dissipate their faculties in what is called easy

reading.

The best books are not read even by those who are called good

readers. What does our Concord culture amount to? There is in this

town, with a very few exceptions, no taste for the best or for very

good books even in English literature, whose words all can read and

spell. Even the college-bred and so-called liberally educated men

here and elsewhere have really little or no acquaintance with the

English classics; and as for the recorded wisdom of mankind, the

ancient classics and Bibles, which are accessible to all who will

know of them, there are the feeblest efforts anywhere made to become

acquainted with them.

who, if he has mastered the difficulties of the language, has proportionally mastered the difficulties of the wit and poetry of a Greek poet, and has any sympathy to impart to the alert and heroic reader; and as for the sacred Scriptures, or Bibles of mankind, who in this town

can tell me even their titles? Most men do not know that any nation

but the Hebrews have had a scripture. A man, any man, will go

considerably out of his way to pick up a silver dollar; but here are

golden words, which the wisest men of antiquity have uttered, and

whose worth the wise of every succeeding age have assured us of; --

and yet we learn to read only as far as Easy Reading, the primers

and class-books, and when we leave school, the "Little Reading," and

story-books, which are for boys and beginners; and our reading, our

conversation and thinking, are all on a very low level, worthy only

of pygmies and manikins.

We are underbred and low-lived and illiterate; and in this respect I confess I do not make any very broad distinction between the illiterateness of my townsman who cannot read at all and the illiterateness of him who has learned to read only what is for children and feeble intellects.

marking the days of your life by the discovery of a great book

How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book! The book exists for us, perchance, which will explain our miracles and reveal new ones. The at present unutterable things we may find somewhere uttered. These same questions that disturb and puzzle and confound us have in their turn occurred to all the wise men; not one has been omitted; and each has answered them, according to his ability, by his words and his life.

It is time that villages were universities, and their elder inhabitants

the fellows of universities, with leisure -- if they are, indeed, so

well off -- to pursue liberal studies the rest of their lives.

Shall the world be confined to one Paris or one Oxford forever?

Cannot students be boarded here and get a liberal education under

the skies of Concord? Can we not hire some Abelard to lecture to

us? Alas! what with foddering the cattle and tending the store, we

are kept from school too long, and our education is sadly neglected.

In this country, the village should in some respects take the place

of the nobleman of Europe. It should be the patron of the fine

arts. It is rich enough. It wants only the magnanimity and

refinement. It can spend money enough on such things as farmers and

traders value, but it is thought Utopian to propose spending money

for things which more intelligent men know to be of far more worth.

This town has spent seventeen thousand dollars on a town-house,

thank fortune or politics, but probably it will not spend so much on

living wit, the true meat to put into that shell, in a hundred

years.

New England can hire all the wise men in the world to come and teach her, and board them round the while, and not be provincial at all. That is

the uncommon school we want. Instead of noblemen, let us have noble

villages of men. If it is necessary, omit one bridge over the

river, go round a little there, and throw one arch at least over the

darker gulf of ignorance which surrounds us.

CHAPTER 4

SOUNDS

What is a course of history or philosophy, or poetry,

no matter how well selected, or the best society, or the most

admirable routine of life, compared with the discipline of looking

always at what is to be seen? Will you be a reader, a student

merely, or a seer? Read your fate, see what is before you, and walk

on into futurity.

I did not read books the first summer; I hoed beans. Nay, I

often did better than this.

Editor' note: In this section and the next, Thoreau speaks of his experience of going within, accessing the present moment, a timeless reverie of living in "the true self." In his own words, in his own "room of transformation," he refers to a mystical phenomenon of awakening, which we often discuss here on Word Gems.

There were times when I could not afford to sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hands. I love a broad margin to my life. Sometimes, in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a revery, amidst the pines and hickories and sumachs, in undisturbed solitude and stillness, while the birds sing around or flitted noiseless through the house, until by the sun falling in at my west window, or the noise of some traveller's wagon on the distant highway, I was reminded of the lapse of time.

I grew like corn in the night

I grew in those seasons like corn inthe night, and they were far better than any work of the hands would have been. They were not time subtracted from my life, but so much over and above my usual allowance. I realized what the Orientals mean by contemplation and the forsaking of works. For the most part, I minded not how the hours went. The day advanced as if to light some work of mine; it was morning, and lo, now it is evening, and nothing memorable is accomplished. Instead of singing like the birds, I silently smiled at my incessant good fortune. As the sparrow had its trill, sitting on the hickory before my door, so had

I my chuckle or suppressed warble which he might hear out of my

nest.

What time is it? well, the time is ‘now’ - what other time would it be?

My days were not days of the week, bearing the stamp of any

heathen deity, nor were they minced into hours and fretted by the

ticking of a clock; for I lived like the Puri Indians, of whom it is

said that "for yesterday, today, and tomorrow they have only one

word, and they express the variety of meaning by pointing backward

for yesterday forward for tomorrow, and overhead for the passing

day." This was sheer idleness to my fellow-townsmen, no doubt; but

if the birds and flowers had tried me by their standard, I should

not have been found wanting. A man must find his occasions in

himself, it is true. The natural day is very calm, and will hardly

reprove his indolence.

my own life was my joy and amusement

I had this advantage, at least, in my mode of life, over those

who were obliged to look abroad for amusement, to society and the

theatre, that my life itself was become my amusement and never

ceased to be novel. It was a drama of many scenes and without an

end. If we were always, indeed, getting our living, and regulating

our lives according to the last and best mode we had learned, we

should never be troubled with ennui. Follow your genius closely

enough, and it will not fail to show you a fresh prospect every

hour. Housework was a pleasant pastime. When my floor was dirty, I

rose early, and, setting all my furniture out of doors on the grass,

bed and bedstead making but one budget, dashed water on the floor,

and sprinkled white sand from the pond on it, and then with a broom

scrubbed it clean and white; and by the time the villagers had

broken their fast the morning sun had dried my house sufficiently to

allow me to move in again, and my meditations were almost

uninterupted. It was pleasant to see my whole household effects out

on the grass, making a little pile like a gypsy's pack, and my

three-legged table, from which I did not remove the books and pen

and ink, standing amid the pines and hickories. They seemed glad to

get out themselves, and as if unwilling to be brought in. I was

sometimes tempted to stretch an awning over them and take my seat

there. It was worth the while to see the sun shine on these things,

and hear the free wind blow on them; so much more interesting most

familiar objects look out of doors than in the house. A bird sits

on the next bough, life-everlasting grows under the table, and

blackberry vines run round its legs; pine cones, chestnut burs, and

strawberry leaves are strewn about. It looked as if this was the

way these forms came to be transferred to our furniture, to tables,

chairs, and bedsteads -- because they once stood in their midst.

I confess, that practically speaking, when I have learned a man's real

disposition, I have no hopes of changing it for the better or worse

in this state of existence.

Editor's note: Thoreau came to see, as many wise have also understood, that man's dark side is not to be expunged but to be transcended. This is so because lessons learned with "the ego" become our sourse of great wisdom.

CHAPTER 5

SOLITUDE

This is a delicious evening, when the whole body is one sense,

and imbibes delight through every pore. I go and come with a

strange liberty in Nature, a part of herself. As I walk along the

stony shore of the pond in my shirt-sleeves, though it is cool as

well as cloudy and windy, and I see nothing special to attract me,

all the elements are unusually congenial to me. The bullfrogs trump

to usher in the night, and the note of the whip-poor-will is borne

on the rippling wind from over the water.

feeling a oneness and kinship with Nature

Sympathy with the fluttering alder and poplar leaves almost takes away my breath; yet, like the lake, my serenity is rippled but not ruffled. These small waves raised by the evening wind are as remote from storm as the

smooth reflecting surface. Though it is now dark, the wind still

blows and roars in the wood, the waves still dash, and some

creatures lull the rest with their notes. The repose is never

complete. The wildest animals do not repose, but seek their prey

now; the fox, and skunk, and rabbit, now roam the fields and woods

without fear. They are Nature's watchmen -- links which connect the

days of animated life.

Men frequently say to me, "I should think you would feel lonesome down

there, and want to be nearer to folks, rainy and snowy days and

nights especially." I am tempted to reply to such -- This whole

earth which we inhabit is but a point in space. How far apart,

think you, dwell the two most distant inhabitants of yonder star,

the breadth of whose disk cannot be appreciated by our instruments?

Why should I feel lonely? is not our planet in the Milky Way? This

which you put seems to me not to be the most important question.

What sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows

and makes him solitary? I have found that no exertion of the legs

can bring two minds much nearer to one another. What do we want

most to dwell near to? Not to many men surely, the depot, the

post-office, the bar-room, the meeting-house, the school-house, the

grocery, Beacon Hill, or the Five Points, where men most congregate,

but to the perennial source of our life, whence in all our

experience we have found that to issue, as the willow stands near

the water and sends out its roots in that direction. This will vary

with different natures, but this is the place where a wise man will

dig his cellar....

Any prospect of awakening or coming to life to a dead man makes

indifferent all times and places. The place where that may occur is

always the same, and indescribably pleasant to all our senses. For

the most part we allow only outlying and transient circumstances to

make our occasions. They are, in fact, the cause of our

distraction.

We are the subjects of an experiment which is not a little

interesting to me. Can we not do without the society of our gossips

a little while under these circumstances -- have our own thoughts to

cheer us? Confucius says truly, "Virtue does not remain as an

abandoned orphan; it must of necessity have neighbors."

I find it wholesome to be alone the greater part of the time.

To be in company, even with the best, is soon wearisome and

dissipating. I love to be alone. I never found the companion that

was so companionable as solitude. We are for the most part more

lonely when we go abroad among men than when we stay in our

chambers. A man thinking or working is always alone, let him be

where he will. Solitude is not measured by the miles of space that

intervene between a man and his fellows. The really diligent

student in one of the crowded hives of Cambridge College is as

solitary as a dervish in the desert. The farmer can work alone in

the field or the woods all day, hoeing or chopping, and not feel

lonesome, because he is employed; but when he comes home at night he cannot sit down in a room alone, at the mercy of his thoughts, but

must be where he can "see the folks," and recreate, and, as he

thinks, remunerate himself for his day's solitude; and hence he

wonders how the student can sit alone in the house all night and

most of the day without ennui and "the blues"; but he does not

realize that the student, though in the house, is still at work in

his field, and chopping in his woods, as the farmer in his, and in

turn seeks the same recreation and society that the latter does,

though it may be a more condensed form of it.

Society is commonly too cheap. We meet at very short intervals,

not having had time to acquire any new value for each other. We

meet at meals three times a day, and give each other a new taste of

that old musty cheese that we are. We have had to agree on a

certain set of rules, called etiquette and politeness, to make this

frequent meeting tolerable and that we need not come to open war.

We meet at the post-office, and at the sociable, and about the

fireside every night; we live thick and are in each other's way, and

stumble over one another, and I think that we thus lose some respect

for one another. Certainly less frequency would suffice for all

important and hearty communications.

I have a great deal of company in my house; especially in the

morning, when nobody calls. Let me suggest a few comparisons, that

some one may convey an idea of my situation. I am no more lonely

than the loon in the pond that laughs so loud, or than Walden Pond

itself. What company has that lonely lake, I pray? And yet it has

not the blue devils, but the blue angels in it, in the azure tint of

its waters. The sun is alone, except in thick weather, when there

sometimes appear to be two, but one is a mock sun. God is alone --

but the devil, he is far from being alone; he sees a great deal of

company; he is legion. I am no more lonely than a single mullein or

dandelion in a pasture, or a bean leaf, or sorrel, or a horse-fly,

or a bumblebee. I am no more lonely than the Mill Brook, or a

weathercock, or the north star, or the south wind, or an April

shower, or a January thaw, or the first spider in a new house.

Chapter 6

I think that I love society as much as most, and am ready enough

to fasten myself like a bloodsucker for the time to any full-blooded

man that comes in my way. I am naturally no hermit, but might

possibly sit out the sturdiest frequenter of the bar-room, if my

business called me thither.

I had three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for

friendship, three for society. When visitors came in larger and

unexpected numbers there was but the third chair for them all, but

they generally economized the room by standing up. It is surprising

how many great men and women a small house will contain. I have had

twenty-five or thirty souls, with their bodies, at once under my

roof, and yet we often parted without being aware that we had come

very near to one another.

CHAPTER 7

Ancient poetry and mythology suggest, at least, that husbandry

was once a sacred art; but it is pursued with irreverent haste and

heedlessness by us, our object being to have large farms and large

crops merely. We have no festival, nor procession, nor ceremony,

not excepting our cattle-shows and so-called Thanksgivings, by which

the farmer expresses a sense of the sacredness of his calling, or is

reminded of its sacred origin. It is the premium and the feast

which tempt him. He sacrifices not to Ceres and the Terrestrial

Jove, but to the infernal Plutus rather. By avarice and

selfishness, and a grovelling habit, from which none of us is free,

of regarding the soil as property, or the means of acquiring

property chiefly, the landscape is deformed, husbandry is degraded

with us, and the farmer leads the meanest of lives. He knows Nature

but as a robber.

CHAPTER 11

We are conscious of an animal in us, which awakens in proportion

as our higher nature slumbers. It is reptile and sensual, and

perhaps cannot be wholly expelled; like the worms which, even in

life and health, occupy our bodies. Possibly we may withdraw from

it, but never change its nature. I fear that it may enjoy a certain

health of its own; that we may be well, yet not pure.

CHAPTER 17

(final words of the chapter)

Thus was my first year's life in the woods completed; and the

second year was similar to it. I finally left Walden September 6th,

1847.

CHAPTER 18

The universe is wider than our views of it.

I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there. Perhaps

it seemed to me that I had several more lives to live, and could not

spare any more time for that one. It is remarkable how easily and

insensibly we fall into a particular route, and make a beaten track

for ourselves. I had not lived there a week before my feet wore a

path from my door to the pond-side; and though it is five or six

years since I trod it, it is still quite distinct.

I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances

confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live

the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success

unexpected in common hours. He will put some things behind, will

pass an invisible boundary; new, universal, and more liberal laws

will begin to establish themselves around and within him; or the old

laws be expanded, and interpreted in his favor in a more liberal

sense, and he will live with the license of a higher order of

beings. In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the

universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be

solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness. If you have

built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where

they should be.

Why level downward to our dullest perception always, and praise

that as common sense? The commonest sense is the sense of men

asleep…

the different drummer

Why should we be in such desperate haste to succeed and in such

desperate enterprises? If a man does not keep pace with his

companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let

him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.

It is not important that he should mature as soon as an apple tree

or an oak. Shall he turn his spring into summer? If the condition

of things which we were made for is not yet, what were any reality

which we can substitute? We will not be shipwrecked on a vain

reality. Shall we with pains erect a heaven of blue glass over

ourselves, though when it is done we shall be sure to gaze still at

the true ethereal heaven far above, as if the former were not?

However mean your life is, meet it and live it; do not shun it

and call it hard names. It is not so bad as you are. It looks

poorest when you are richest. The fault-finder will find faults

even in paradise. Love your life, poor as it is. You may perhaps

have some pleasant, thrilling, glorious hours, even in a poorhouse.

The setting sun is reflected from the windows of the almshouse as

brightly as from the rich man's abode; the snow melts before its

door as early in the spring. I do not see but a quiet mind may live

as contentedly there, and have as cheering thoughts, as in a palace.

Cultivate poverty like a garden herb, like sage. Do not trouble

yourself much to get new things, whether clothes or friends. Turn

the old; return to them. Things do not change; we change. Sell

your clothes and keep your thoughts. God will see that you do not

want society. If I were confined to a corner of a garret all my

days, like a spider, the world would be just as large to me while I

had my thoughts about me. The philosopher said: "From an army of

three divisions one can take away its general, and put it in

disorder; from the man the most abject and vulgar one cannot take

away his thought." Do not seek so anxiously to be developed, to

subject yourself to many influences to be played on; it is all

dissipation. Humility like darkness reveals the heavenly lights.

The shadows of poverty and meanness gather around us, "and lo!

creation widens to our view." We are often reminded that if there

were bestowed on us the wealth of Croesus, our aims must still be

the same, and our means essentially the same.

Superfluous wealth can buy superfluities only. Money

is not required to buy one necessary of the soul.

We know not where we are. Beside, we are sound asleep

nearly half our time. Yet we esteem ourselves wise, and have an

established order on the surface. Truly, we are deep thinkers, we

are ambitious spirits! As I stand over the insect crawling amid the

pine needles on the forest floor, and endeavoring to conceal itself

from my sight, and ask myself why it will cherish those humble

thoughts, and bide its head from me who might, perhaps, be its

benefactor, and impart to its race some cheering information, I am

reminded of the greater Benefactor and Intelligence that stands over

me the human insect.

There is an incessant influx of novelty into the world, and yet

we tolerate incredible dulness. I need only suggest what kind of

sermons are still listened to in the most enlightened countries.

The life in us is like the water in the river. It may rise this

year higher than man has ever known it, and flood the parched

uplands; even this may be the eventful year, which will drown out

all our muskrats. It was not always dry land where we dwell. I see

far inland the banks which the stream anciently washed, before

science began to record its freshets. Every one has heard the story

which has gone the rounds of New England, of a strong and beautiful

bug which came out of the dry leaf of an old table of apple-tree

wood, which had stood in a farmer's kitchen for sixty years, first

in Connecticut, and afterward in Massachusetts -- from an egg

deposited in the living tree many years earlier still, as appeared

by counting the annual layers beyond it; which was heard gnawing out

for several weeks, hatched perchance by the heat of an urn. Who

does not feel his faith in a resurrection and immortality

strengthened by hearing of this?

Who knows what beautiful and winged life, whose egg has been buried for ages under many concentric layers of woodenness in the dead dry life of society, deposited at first in the alburnum of the green and living tree, which has been gradually converted into the semblance of its

well-seasoned tomb -- heard perchance gnawing out now for years by

the astonished family of man, as they sat round the festive board --

may unexpectedly come forth from amidst society's most trivial and

handselled furniture, to enjoy its perfect summer life at last!

I do not say that John or Jonathan will realize all this; but

such is the character of that morrow which mere lapse of time can

never make to dawn. The light which puts out our eyes is darkness

to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more

day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.

THE END.

|

Postscript:

Henry David Thoreau has influenced a great many since those days on the pond; myself included.

As a freshman at university, more than 50 years ago, I still recall purchasing a copy of Walden in the campus bookstore. So moved was I by this wise man’s discourse on Nature, solitude, and independence, I seriously considered going back to the old farm; and this, in spite of all the ill-will and antipathy I’d earned for myself at home, given my disagreement with conventional ways. Mercifully, as this would have been a grave error, my father perceived more clearly than I and strongly cautioned against a return to the old life, admonishing that I was “made for something else.” Dispatching me thus, he sent me on my long journey.

|

|

Marvel's The Watcher is like the mind’s silent background witnessing presence

Marvel's The Watcher, introduced in Fantastic Four #13 1963

The silent Watcher merely observes, does not interfere, will render judgment, a sense of propriety or lack thereof, concerning the activities of the thinking mind. It's the part of us that knows we're thinking.

It is consciousness aware of itself, observing itself. Emily Dickinson spoke of the same in her “This Consciousness that is aware.”

And when we enter this self-monitoring, it might be the most powerful aid in terms of unfolding the entire inner person.

like corn growing in the night

There are too many metaphors here within short compass, but -- how does transformative change transpire?

It will come to be, as Thoreau used the phrase in Walden, “like corn growing in the night” – imperceptibly, unobtrusively, unsensationally – and you will be decimated, your world rocked, by realization of what had been around you, all of your life, but utterly unapprehended.

READ MORE

|

|