|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Dante's Divine Comedy

return to the main-page article on "Hell"

“Through me you pass into the city of woe:

Through me you pass into eternal pain: Through me among the people lost for aye. Justice the founder of my fabric moved: To rear me was the task of power divine, Supremest wisdom, and primeval love. Before me things create were none, save things Eternal, and eternal I shall endure. All hope abandon, ye who enter here.” The Comedy"

Editor's note: The "Divine Comedy" helped to popularize the error that suicides are more evil than most. See the above "7th circle of Hell."

a 2007 facial reconstruction of Dante

Why is it called a “comedy”? “Comedy” once meant “it has a happy ending,” as opposed to a “tragedy”; we could use some of that today, the "comedy" part.

Dante’s “Comedy” might be the most complex poem ever written. As literary art, on many levels, it is unparalleled; a masterpiece of allegorical latticework. Every educated person should want to know something about Dante’s epic poem. Its influence upon Western civilization has been massive. There is so much embedded in this writing that Dante scholars might spend their entire careers exploring the nuances of its thousands of metaphorical allusions. I’d like to recommend the 12-hour lecture series by Professors William R. Cook and Ronald B. Herzman. Along with erudite survey, they spice discourse with humor and graciousness. It’s a pleasure to listen to them. My comments herein derive from their years of careful investigation, but also my own observations.

Professors William R. Cook and Ronald B. Herzman

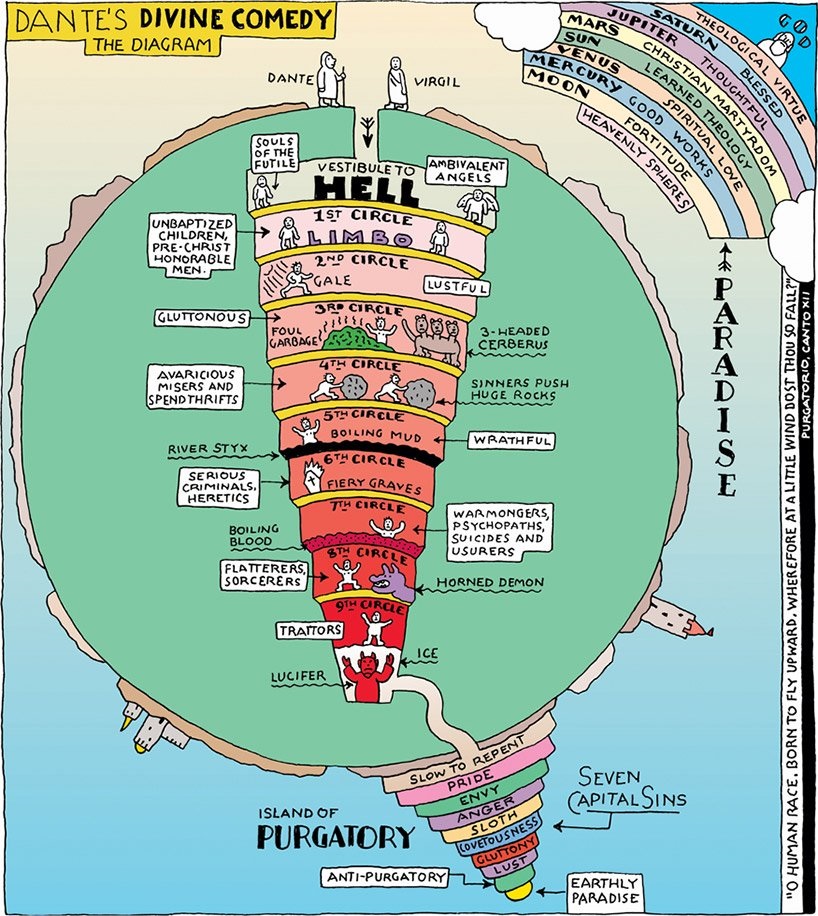

an overview of the structure of “The Comedy” Most people, if they know anything about this poem, are familiar with Dante’s descent into Hell. However, the itinerary included additional rest-stops. "The Comedy” has three main parts: Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory), and Paradiso (Paradise). There are 14,233 lines in the poem. This literary mass is subdivided into 100 cantos (songs), which might be thought of as chapters. After an introductory canto, each of the three major ports-of-call – Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise – claims 33 cantos. Each canto issues with approximately 140 lines. These are structured in tercets, groupings of three lines. The rhyming scheme follows an order of aba, bcb, cdc, ded, ....

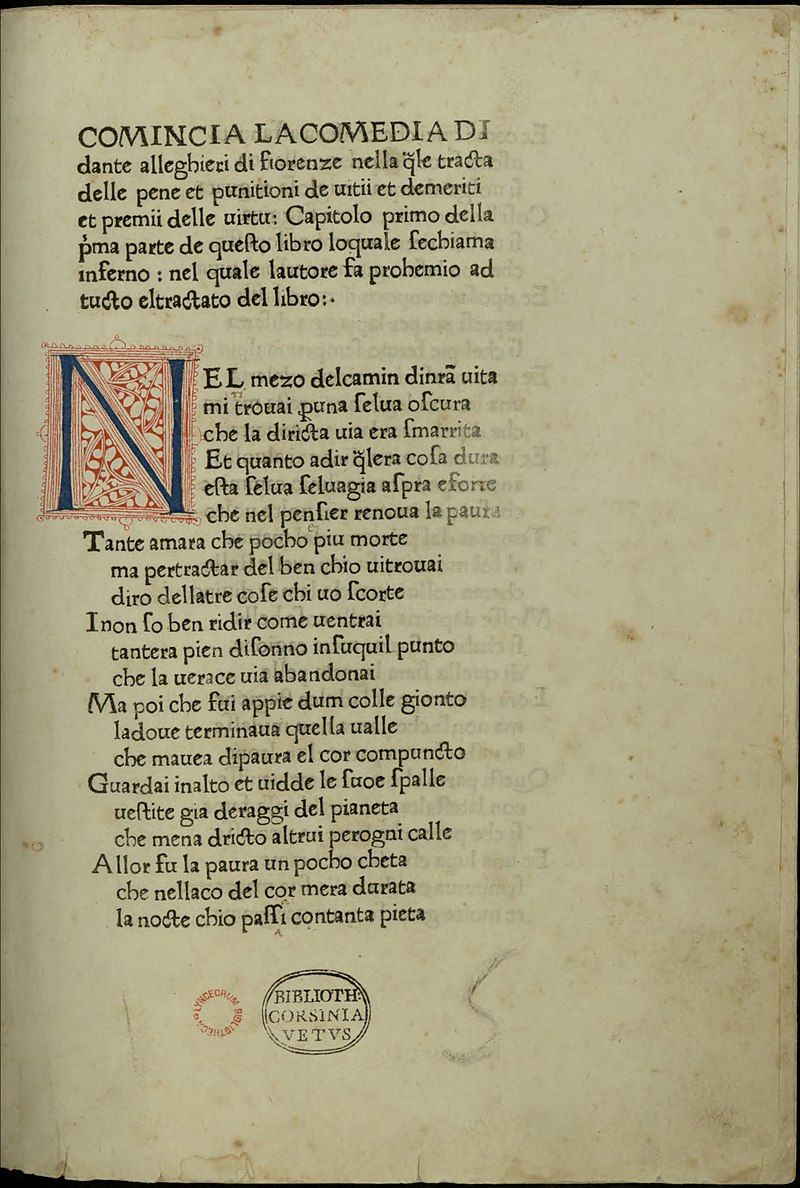

These three other-worldly kingdoms are comprised of a “9 + 1” configuration: Hell has nine circles plus Lucifer at the bottom. Purgatory is a mountain of nine rings with the Garden of Eden at the summit. Paradise is divided into nine celestial realms, capped by the Empyrean, the dwelling place of God. The professors remind us that Dante wrote his work in Italian, which means that the rhyming structure was made to work in that language with no easy cross-over to English. The poem is so massive and complex that hardly any, maybe none, of the available English translations do justice to the artistic edifice created by Dante. The best way forward here, for serious students, assuming Italian is not one’s native language, might be to study a version that offers the original Italian text on one side of the page, with the English rendition – possibly, a prose translation, plus historical notes -- on the opposite.

But none of this byzantine anatomical structure suggests why "The Comedy” should be studied by moderns. On the level of good data, almost everything Dante says is fairly askew; as we would say, "it's from the Middle Ages": An outdated, errant Ptolemaic view of the cosmos – with the Earth at universe's center, and the Sun orbiting – rules "The Comedy.” Much of the “stage scenery” of Hell has been “cut and pasted” from Virgil’s account in the Aeneid. Is there really a “River Styx” in the infernal regions? Even true-believer Catholics might be taken aback to realize that a traditional RCC doctrine finds its roots in the testimony of the noble pagan, Virgil. Are we to subscribe to a “holy place of torture” at the center of the Earth? What about our planet’s iron-nickel core that we need for the magnetosphere, which wards away cosmic radiation? Even Pope Francis finds Dante’s mythology too much to seriously entertain, and dismissively waves it all away.

We could go on. While these ideas have had a long run, infusing the masses with heavy doses of fear and guilt -- none of it is true.

On the level of hard-core reality, of factual information, of solid evidence, Dante fails us. Even so, I like his work. It's about asking important questions, ones that every human being must ask. All great literature stirs us to grander perspective. “The best of a book is not the thought which it contains, but the thought which it suggests; just as the charm of music dwells not in the tones but in the echoes of our hearts.” John Greenleaf Whittier “Sometimes questions are more important than answers.” Nancy Willard “It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.” Decouvertes “Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.” Voltaire “Asking the right questions takes as much skill as giving the right answers.” Robert Half “To be able to ask a question clearly is two-thirds of the way to getting it answered.” John Ruskin

Dante’s personal life was a huge mess. He had a big question, though, the answer to which he hoped would put things right. He wrote 'The Comedy,' primarily, to sort things out in his own head. As I infer from his writings, Dante was a sincere seeker of truth. Anybody with this kind of personal integrity will eventually find the truth – guaranteed. And it doesn’t matter so much if right now one is burdened with mythologies of “infallible” religious doctrine. On the homepage, I quote Philip Hamilton who speaks of seekers of truth as constituting “a spiritual society.” This bond among those mutually questing for what’s real is something “of which we can never be deprived, for it rests in the heart and soul of the man who has acquired it.” This is a very beautiful concept and reflects a spirit of brotherhood and sisterhood to be experienced in Summerland among all those whose hearts are yearning for greater perceptions of the truth. Editor’s note: It is for this reason I stated that I especially enjoyed the lectures of the two professors. It became clear that they've studied Dante, virtually, as a life's work, as their current best means of accessing answers to the big questions of mortal existence.

Inferno, Canto 1, Line 1 The poem opens with Dante announcing that he is “lost in a dark wood,” an impenetrable forest of opaque shadows, representing life’s malaise, injustice, and joylessness. He was a man desperately searching for a "happy ending" to the meaninglessness and unhappiness engulfing him.

What has happened to produce this existential crisis? What is wrong with Dante’s life? – pretty much everything, as he’d tell the story.

While the structure of 'The Comedy' must be judged as complex, with its multilayered display of special number, rhyming pattern, and groups within groups, there’s a simpler reason why almost everyone will find this work impenetrable. Dante is conducted through the ascending stages of the afterlife by tour guides. But we, also, need a guide to read the account of his journey. Why is this? “The Comedy” could be seen as a long chronicle of numerous conversations. Dante meets a lot of people along the way; some in Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Some of these “locals” were once the luminaries of Earth – Adam and Eve, Alexander the Great, Justinian the Emperor, Thomas Aquinas, and others. No problem so far; we easily recognize these names on the printed leaflet for the play. But, we all begin to stumble clueless when Dante chats with people who once lived in his hometown of Florence -- John Smith and Mary Jones, well known Florentines of the old neighborhood. Dante does not go out of his way to fill us in on background information. Additionally, the poet might refer to points of local interest, culture, or convention. All of this would have been familiar to a reader in Dante’s day, with no need for elaboration, but a modern audience, lacking antecedent moorings, quickly flounders. It would be like archeologists, a thousand years from now, digging up the remains of the American Civilization. They come across a reference – "the fourth of July." It’s assumed there’s nothing important here, just a hum-drum marking of time. However, we all know that the fourth of July means much more than a day of summer, and we don't need it explained to us. And this is our problem with reading “The Comedy.” It’s packed with, to us, obscure references to people, customs, and places which have no meaning to moderns. And this is why, for the serious student of Dante, the text of the poem is buttressed with, up to, several volumes of notes and commentary; far longer and more extensive than the poem itself.

in this swirling maelstrom of minutia, Dante’s main point could get lost; or not Some commentators say that the way to understand “The Comedy” is to view it as a work of an exile. Dante was on the run when he wrote his poem. All this is true - but we need to go deeper. Dante’s banishment, a status of an outsider, helped him to see clearly what he wanted to say, but the expatriation itself was not uppermost on his mind. He wasn't thrilled about it but finally accepted his sufferings, realizing that he could offer a message as legacy. What was going on in his life that produced a sense of being “lost in a dark wood”?

this poem is written by one who had nothing left to lose Dante was a man who had lost just about everything worth having in life: his city, his homeland, friends and family, career, professional esteem, reputation, income and savings, the girl he loved, and even the security of safe harbor. There were many who wanted to kill him. "The Comedy" is written by someone who had nothing left to lose and, therefore, he spoke frankly; far too unguardedly for the likings of many. He threatened the Establishment. Dante's pen would defend, in a timeless way, as no sword could. Doubtless, in his dark hours, he took solace from the New Testament words of Jesus: don't be afraid to speak the truth, a day will come when everyone will have to admit that you were right all along Don’t be intimidated. Eventually everything is going to be out in the open, and everyone will know how things really are. So don’t hesitate to go public now. Don’t be bluffed into silence by the threats of bullies. [They can only kill your body, but there's] nothing they can do to your soul, your core being. Jesus of Nazareth, The Message translation In his deeper message, Dante was correct regarding aspects of life that matter most.

a brief summary of Dante’s life-situation He had become embroiled in the politics of his day. Then as now, on the municipal, national, and international levels, there were those grasping for more power over people. It's a well-worn and dreary theme. The Holy Roman Emperor, dissatisfied with being somewhat of a figurehead, endeavored to exert more active control over Italy. His main rival to this end was the Pope. Italy in 1300 was not a unified country (this would not occur until the 1800s) but a collection of city-states. Florence, a city-state, operated as an independent country, in competition with neighboring city-states, also sovereign nations. The Italian city-states were forming military alliances, some with the Pope against the Emperor, with others for the Emperor. These two major political factions were called the Guelphs, supporting the Pope and his armies, and the Ghibellines, who backed the Emperor. Dante was a card-carrying Guelph. During the years prior to 1300, Florence was ruled by Guelphs. Dante himself, very briefly, held high office in the city. However, as is often the case, factionalism does not cease when a party comes to power, but will metastasize and divide once again. The Florentine Guelphs split into two power blocks, the “Black Guelphs” and the “White Guelphs,” with Dante a member of the latter. When his faction fell from grace, he became a man with a "price on his head."

But why should he have to flee the city? Think of the deadly street fights in Romeo and Juliet.

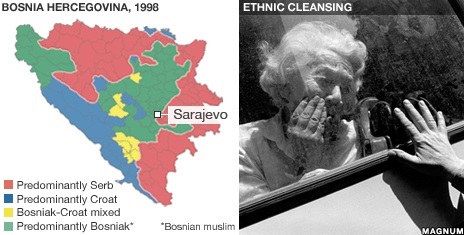

neighbor against neighbor Think of the “ethnic cleansing” afflicting Bosnia-Herzegovina in the 1990s, part of a civil war. Great atrocities – neighbor against neighbor -- occurred in the wake of the disintegration of the former Yugoslavia into individual nation-states, a power vacuum created by the regional fall of communism.

an intricately woven matrix of long-held grievance The professors explain that the hatreds placarded in Dante’s Florence were fueled by much more than partisanship toward Pope or Emperor. That was just the official excuse. People kept track of past insults and injuries. Memories were long with forgiveness in short supply.

Dante traces the roots of the city's poisonous factionalism to a single event nearly 100 years prior. Local history, the stories that people grew up with, led Dante to assert that he could pin-point the actual incident that changed everything in Florence. It was the year 1215. Everybody seemed to know about this. A young groom jilted his bride-to-be when he received a better offer. The opportunistic fellow ended up being murdered by the fiancée’s offended family; in fact, a lot of people died as a lust for vengeance, over the ensuing years, spun out of control with blood in the streets.

By 1300, the well-nurtured enmity had hardened into a settled state of mind. A contemporary of Dante opined that the spirit of Florence had devolved to one gigantic grasping thrust for power. Each group hoped to gain the ascendancy, at the expense of all others. The air of Florence was quite toxic to breathe. With top-dog political status, one could put friends and relatives into positions of leadership, thereby solidifying control over the legislative process. Having secured dominion, the cabal could rake in money from bribes, taxes, sweetheart deals, "consulting and lecturing fees," strategic placement on "boards of directors," that sort of thing -- all feathering one’s nest.

pay-back time Dante would have made enemies in his rise to Florentine civic office, and so, when the winds of power shifted in the great city, it was pay-back time by those who saw themselves as victims of his good fortune. A little "ethnic cleansing," Florentine style, seemed the right thing to do. It all came tumbling down for Dante in 1301. He was out of the city when "the revolution" came, and he dared not go back. He died in exile 20 years later. Most of his time "in the wilderness" was spent writing "The Comedy."

a heavy sense of isolation and being out-of-the-loop We begin to perceive a dark cloud of introspection, mandated by ostracization, hovering over Dante. Before we investigate how it influenced the poet, let’s look at the metaphors of exile in “The Comedy.”

What’s up with Virgil as Dante’s guide? Dante identified not only with Virgil but with Virgil's fictional character, Aeneas. The poet Virgil (70 BC – 19 BC) wrote the Aeneid at the behest of Augustus. The Emperor, dismayed at flagging civic spirit, had embarked upon a “make Rome great again” campaign. Virgil was to revive good feelings toward the Empire by reminding a jaded populace of its auspicious past and glorious mission in the world. Augustus’ cheerleading of the troops, in good measure, took the form of Aeneas, the hero of the Aeneid. Born of the royal Trojan family, Aeneas escaped the burning city of Troy (1174 BC), which was decimated by the conquering Greeks, as reported in the Iliad. But Aeneas, having lost everything, and now forced into exile, headed for a "happy ending," and was prophesied to found a great city and nation; that would be Rome, as Augustus' spin-doctoring had it.

It’s not hard to see the parallels with Dante’s life, but there’s another major analogue provided by Aeneas. As Aeneas takes the long road home to what would become Rome, he packs a lunch and makes a day-trip into the underworld, Hades. Therein, he meets all sorts of colorful characters, but the most meaningful encounter is with his departed father, Anchises. Editor's note: Completing the parallel, in Virgilian fashion, Dante in his journeys meets a forebear, a great-grandfather, who also advises him. The patriarch encourages his son, who had suffered great trial in the collapse of Troy, to be strong. Anchises’ words would become a virtual mission-statement in the mouth of Augustus for the Roman Empire. Essentially, the message to Aeneas was this: “The Greeks were great philosophers and artists, and we learn from them; but there is one thing, one great talent, that will come to define your descendants. It will be an honoring of the rule of law, leading to universal justice. Your children will govern the world and bring peace and stability to all nations.” Now we're getting very close to the core message of "The Comedy."

meanwhile, back at the toxic waste dump that is Florentine politics Early in his exile, Dante pondered the possibility of making a comeback in Florence, recapturing what he had lost. After a time, however, he realized this was not going to happen. In this resignation, Dante began to look farther afield for meaning in his life. He thought about the noxious rivalries back home, all of the “hurray for our side” sentiment, the “I and my friends and relatives will win, and all of you must lose” mentality. He started to see that he, and his city, was on the wrong track, and no good could come from the endless strife. Instead of scheming with self-serving objectives, “How can I win the next election?” or “How can I fool’em today, posturing as a statesman but inwardly living as a conniving cheat?” he began to entertain larger questions: How can anyone ever find true happiness in an unjust society? What does it mean to be a responsible citizen, a devout Christian, a good person? How will the evil of this world be dealt with? Is there justice in the universe? How can one live a good and honest life in such a corrupt world? How will God turn all of the chaos on planet Earth into some kind of happy ending?

newcomers to 'The Comedy' might imagine that Dante will offer lavish praise to the RCC, holding it up as humanity’s great hope for a blessed life; well, yes and no, but not really Dante writes as someone really burned out on partisan politics. It makes him sick. And so he’s in no mood to grant any kind of “blank check” subservience to another political machine, an exclusivist Dear Mother Church.

Dante's contention, generally unknown, is that a great many of the leading RCC clergy, a great many of the Popes – are in Hell. Dante has a lot to say about the sin of “simony.” We’re not so familiar with this word today, but it refers to a guy in the New Testament book of Acts, a Simon Magus.

"make me a rock-star, too" An enterprising fellow, Simon was impressed by the notoriety enjoyed by Peter and John, and so he approached the apostles with an offer: “How much will it cost me to be religious rock-star, too.” This didn't go over too well with The Fisherman. If you check the translations on this, basically, Peter told him to go to hell. Simony is the crime of making good money by doing God’s work – what Thomas Paine blasted as “pomp and revenue.” It is the sin of simony that riled up Jesus so much when he threw everybody out of the temple. Any “non-aligned” historian-scholar will tell you that, for a very long time, the Papacy was bought and sold in the marketplace, controlled by a few rich families who jostled back-and-forth for this plumb job. Nice work if you can get it. conspiratorial, malicious, institutionalized simony And it takes only cursory literary analysis to understand that Dante, a man on the run from the poisonous spirit of Florentine factionalism, the merchandizing of the common people by “public servants,” now saw, very clearly, the same kind of oppressive “buying and selling,” an orchestrated and institutionalized simony, polluting the greedy ranks of Dear Mother Cult. Editor’s note: As stated elsewhere, the afterlife reports concur with Dante that many of the Popes languish today in a dark rat cellar.

from 'Comedy' to 'Divine Comedy' With the publication of “The Comedy,” it is no surprise to learn that the RCC condemned Dante’s work as heretical. But here’s the rest of the story. Over the next 200 years -- despite the censoring, or maybe because of it -- “The Comedy” became lauded as one of the greatest literary masterpieces of all time. Well, how awkward for Dear Mother. It becomes increasingly difficult to maintain a ban on something that everyone is so thrilled about, it’s just not cachet, and so, as a publicity move, like a cheap politician shifting gears with the latest poll numbers, Dear Mother Cult reclaimed Dante’s poem as one of its own. Moreover, She now began to refer to it as “The Divine Comedy.” Editor’s note: Dear Mother Church has a long history of this kind dark-spirited opportunism. Not uncommonly, some of the brotherhood and sisterhood service-orders were initially condemned by Rome, suspiciously viewed as competition. For example, when Francis of Assisi died (only about 75 years before the writing of "The Comedy"), the Church murdered his followers, the Fraticelli, burning them at the stake as heretics. See the report by historian Kenneth Clark. Later, however, Francis became so beloved by the lay people that the Church had no choice but to claim that She'd been leading the parade all along, and so She had to make Francis a "saint." Or even a simple thing like the popularity of a song will threaten the power-mad hierarchy. As discussed in "The Wedding Song" book, early on, the Church refused to allow it to be played at weddings, calling it "secular." However, so many brides insisted on having this music for their big day that the Church was forced to recant, sing a new song, and then, in a 180, claimed it as their own, insisting that the song's message supports Church authority. It does nothing of the kind, but that's another story. We could offer many more examples of this ecclesiastical Machiavellianism. But we need to keep in mind that any politician, or any person, led by the dysfunctional "false self," is never interested, for its own sake, in any good work, any charitable effort, anything that might help society -- if that beneficence does not accrue to the account of the ego-led politician. The "Needy Little Me" will be against anything that it cannot dominate and does not contribute to its quest for power and control.

as we read 'The Comedy,' and also learn more of Dante’s life, we can almost feel the burgeoning change in his spirit allowing him to see more He’s no longer a petty politician, impressed with his own rise in society. Dante is evolving into a “citizen of the world” as he contemplates universal principles, applicable not just to party-faithful friends and relatives, but to all peoples everywhere and in all eras. But, while his sentiments were altruistic, he wrote too soon. He didn't see nearly far enough. More than he knew at the time, his views were still altogether colored by what Herodotus called, the “nomos” of his day, provincial custom and convention. For example…

Dante believed that universal peace and justice would come by way of a worldwide state-and-church dictatorship, guaranteeing that no one could step out of line. He wanted to make sure that the poisonous politics of Florence could never happen again. We get it. This was a man who had lost everything in the wake of the toxic factionalism in his home town. The way forward, as he saw it, was to reinstitute the steel fist of the “Pax Romana,” the good old days when the trains ran on time because the Caesars wielded a big sword and everyone knew his place in society. This is why, in Dante’s vision of Heaven, we find Roman Emperors as a pantheon of political saints. They knew how to run a tight ship, let me tell you. No “Romeo and Juliet” stabbings in the street on their watch, that's for sure. With this image in mind, Dante believes, it is no accident that God’s Church should find headquarters in Rome. This seemingly fortuitous juxtapositioning of state and church, in one great city, surely, is portentous of God’s will. Yes, the present Church is a gangster, it’s utterly corrupted and worldly, thought Dante, but this doesn’t mean it doesn’t have a prime role to play in bringing peace and justice, the ideal society, to the Earth. However, as we’ve said, Dante wrote too soon.

Dante could not escape his cultural conditioning. He believed that an all-powerful Church was absolutely required to make humans more godly God’s hands are tied, sighed Dante. God holds his nose, God frets and is dismayed, it's true, but is forced to use the agency of the corrupted, worldly Church to save sinners. Yes, it is using evil to fight evil, and that's not good, but how else will the great unwashed of planet Earth be cleansed in the Blood of Christ? As unfortunate and despicable as it all is, we can hear Dante reasoning, the Church, of cosmic necessity, must be a partner to the saving of the world.

Well, there is so much wrong with the foregoing, we hardly know how to respond. Virtually every word of the inferred reasoning of Dante is simply patent error. None of it is true. It could be said that the entire Word Gems battery of writings serves to dismantle these premises of the poet’s argument.

Through a heavy dose of aversion-therapy, Dante had been thoroughly sensitized against 'hurray for our side' party politics. But here’s the real solution to the 'me against all' problem Dante sorrowed about. In my writings, not infrequently, I reference the testimony of Spirit Guide Elizabeth Fry on the other side. I find both her words and tone so inspiring. I’d like to draw particular attention to how she emphasizes “no one here wants to override another, no one wants to even appear to be important or to aggrandize the self.” How different is this sentiment from the poisonous politics of “me-ism” on the streets of Florence. I conclude this article by leaving you with the words of Elizabeth (via Leslie Flint). This is the real solution to world injustice that Dante sought – a ratcheting up of consciousness.

I would say to you, above all things, if you want to discover truth, avoid men of power and position

"There are no actual leaders [here] as such." In the "real world," in the better neighborhoods of Summerland, there is no ruling elite, strutting with ostentation on a cosmic stage before a merchandized citizenry; all such vainglorious display of Small Ego will be gone with this world. People in Summerland are taught - if they're of a mind to want to be taught - that all might rise to the highest heights of development; no one is second-class; there are no holier-than-thou bureaucratic functionaries, lording it over the plebs. Nevertheless, there is de facto leadership; there are august ones, exceedingly wise, highly revered, and everyone knows who they are. These are they who perceive the inner-workings of natural law; have entered the depths of sacred consciousness; are learned, via personal experience, in the hidden ways of God. These servants-of-all are at our disposal, "at the calling of our hearts." If there's a special project, or a special question, and we need to know; if an expert is required who possesses rare knowledge; such advanced person, equal to the task - possibly, thousands of years old - will be summoned, even from higher dimensions normally unavailable to us; and he or she will visit Summerland to personally instruct one requesting knowledge. "There are no actual leaders [here] as such" - because each person in the afterlife must direct his or her own destiny; but when we need specialized advice, and are willing to ask for it, we will call on authentic leadership, ones who have gone before, servant-authorities who understand perfectly what to do. These are the real elites of the astral realms.

postscript: Dante's glimpse of glorious human evolution, the 'trans-humanization' Nearing the conclusion of “The Comedy,” we sense that the poet, himself, his expanding perceptions of human destiny, becomes more complex than his writing. Dante invents the term “trans-humanize.” We need to transcend common notions of the human condition. We need to go beyond better manners and better laws and better rulers, and all externals, helpful as they may be. "Trans-humanize" becomes Dante's first glimmer that human advancement will not be achieved simply by living in the best neighborhoods of Heaven. We need to go deeper, we need to be changed from the inside out. Dante may have died still trapped in the old doctrinal concepts, but there were cracks in the granite. Soon the Florentine bard will be exclaiming with Elizabeth Fry: “God is not found in buildings or places" -- not even the empyreal levels of Heaven, but -- "God is found within one’s soul, within one’s inner consciousness.”

an after-death visitation by Dante to his son Lilian Whiting, reports in “The World Beautiful”: Boccaccio (1313-1375), Dante (1265-1321) Boccaccio, in his Life of Dante, relates that when The poet’s sons, Pietro and Jacobo, were anxiously Then it occurred to Jacobo to ‘That which you seek is here’; and having

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|