|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Thomas Paine the Preeminent U.S. Founding Father, Defender Par

Thomas Paine (1737 - 1809)

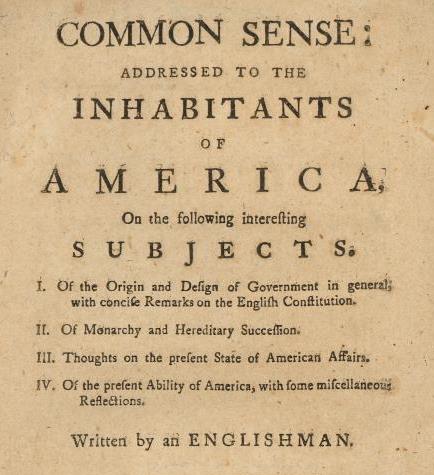

Thomas Paine’s most devastating quality was his constancy. We humans are not generally famous for our fidelity, even to ourselves, are we? Thomas Paine was faithfulness personified. He stayed with his towering democratic ideals to his bitter, bitter end. And, in pursuing those uncompromising democratic ideals, he earned a vast volume of hatred and rejection from continents of human beings. He is a candidate, a candidate for being the most valuable Englishman – ever! And if that is true, why do so few British people even remember his name? Thomas Paine was born here, in this little town of Thetford in the county of Norfolk in England on January the 29th, 1737. He was an only child, and he was brought up in the Quaker faith. But Tom could not follow the dictates of any creed except his own evolving humanitarian belief. At the age of thirteen years in 1750, Thomas Paine was taken away from this grammar school, and he began learning the trade of stay-making, to be the maker of ladies’ corsets; perhaps, a not irrelevant beginning for a man who, later in life, was to fight for the decent rights of women. Tom Paine wandered uneasily around southern England, stay-making. He married, and his young wife died. Then, in the year 1761 he broke under the disturbing strain of corseting women, and he joined the Excise Service. He became a customs officer. And by the year 1768 he was stationed here at Lewes, in the county of Sussex. This is the very house that he lodged in. However, it was at this White Hart Inn that his far-flung genius began to humbly bud. In this building, during Tom’s residence in the town, there was a debating society, and he joined it. And he began to speak. Now, England at that time and, of course, its vassal nations of Wales, Scotland, and ever-fighting Ireland, was bent into cruel social shapes by a class structure of awesome proportion. And it took a brave man to object, and it could mean transportation out of greater Britain – or even death. And to underline the agony, on the throne of England during that period were the unattractive, reactionary German kings, ranging from George I to George IV. Thomas Paine was now 31 years old, and for most of those 31 years he had been watching and listening and thinking. And he had begun to arrive at a general conclusion regarding the proper rights of human kind. And it was here that he began to utter those opinions to the local people. One of the members of this debating society, a Mister Lee, inscribed a verse about Tom’s ability at this time: Thy logic vanquished error, and thy mind, no bounds but those but right and truth can find. A humble poem meant for a few local townspeople; but, as I will demonstrate, astoundingly prophetic! And then in 1772, Thomas Paine moved into the lethal field of practical, national politics. Excise officers, customs men, were paid barely a living wage, and Tom composed his first political pamphlet, quote: Poverty, in defiance of principle, begets a degree of meanness that will stoop to almost anything. A thousand refinements of argument may be brought to prove that the practice of honesty will be still the same, in the most trying and necessitous circumstances. He who never was an hungered may argue finely on the subjection of his appetite; and he who never was distressed, may harangue as beautifully on the power of principle. But poverty, like grief, has an incurable deafness, which never hears; the oration loses all its edge; and "To be, or not to be" becomes the only question. Tom was asking a simple cogent question: How can you expect Excise officers, or anyone else, to be honest, if you keep them very poor? Thomas Paine took those words to the British Parliament. He begged and cajoled many members, but the Excise men’s lot was not improved, and Tom Paine, a very early trade unionist, was sacked from the Excise Service. Tom was now beginning to learn the rough reality of our human society, but – thank God! – as he was rejected by the men at the center of government, he was embraced by their betters, outside of it. Oliver Goldsmith embraced him. And, most importantly and significantly, the great American Benjamin Franklin recognized the quality of Tom Paine and, thereby, did the incipient United States of America an incalculable good turn. Indeed, when Benjamin Franklin, in this very room, here in London, in the year 1774, held out his hand to Thomas Paine, it could soundly be argued that that event literally signified the true beginning of the great North American republic. Benjamin Franklin looked closely at Thomas Paine - at the militant, democratic qualities that Thomas Paine carried with him, and urged Tom to get the hell out of Britain, and to sail immediately for America. Paine agreed, and departed for this then-colonial city of Philadelphia. He carried with him a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin: The bearer, Mister Thomas Paine, is very well recommended … as an ingenious, worthy young man. By January 1775 Thomas had truly discovered the potential of the American way of life, and he quickly became the editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine. When he took that job on, the printer was selling 600 copies per month; three months later the circulation had risen to 1500 per month. What was Tom writing about that attracted American colonialists? Well, he wrote widely. He wrote an article titled “African Slavery In America.” He asked for the total abolition of slavery. This moral demand shocked and disturbed slave-owning Americans; but, just four weeks later – hallelujah! – the first American anti-slave organization was started, here, in Philadelphia. Tom Paine wrote about the moral rightness of a war of liberation. He wrote about the impossibility of unilateral pacifism; particularly, when a country is occupied by an alien military presence, whatever that might be. He wrote, I am thus far a Quaker, that I would gladly agree with all the world to lay aside the use of arms, and settle matters by negotiation; but unless the whole will, the matter ends, and I take up my musket and thank heaven he has put it in my power. Amen. And Thomas Paine wrote about the rights of women; not about privileges for woman at the price of injustice toward men and children, as much of today’s feminist movement advocates, but something quite different – full humanitarian rights for all women. And Tom Paine even preceded Mary Wollstonecraft – that truly great feminist – in this very proper mission. And then, unexpectedly, from one extremity of the 13 British colonies in America to the other, revolution against England, the whole country, began to erupt. The idealistic complaint that the American colonies leveled against England was carried in the slogan, “No taxation without representation!” The Americans objected to being told how much tax they would have to pay by a British Parliament over in London where they had no members of that Parliament. There were, of course, many other reasons why trouble was warming in America, but “No taxation without representation!” was the overall rallying shout. And on this democratic issue, King George III was stubbornly unbending. And it was he who inspired the dispatch of additional British troops to the American colonies, where, here, at this town of Lexington – indeed, on this very green – some of those British soldiers came into conflict with armed American colonial militia. It has been debated that one of the Americans opened fire, and the British replied, and killed 7 American colonialists. The date was April 15, 1775. But even after this shocking event, leading Americans urged appeasement with England. Benjamin Franklin, still over there in London, said, No American, drunk or sober, has ever favored separation from the mother country. Thomas Jefferson stated, I’m still looking with fondness towards reconciliation with Great Britain. And George Washington was adamant: If you ever hear that my joining in any such measures as separation from England, you have my leave to set me down for everything wicked. But our Tom, the sometime corset-maker from Thetford in England, didn’t see the deaths at Lexington, and the royal politics that lay behind those deaths, at all like Franklin, Jefferson, or Washington. Tom began to compose words which expressed exactly what he deeply felt. He turned first on George III whom he ardently despised: I rejected the hardened, sullen tempered Pharaoh of England for ever; and disdain the wretch, that with the pretended title of FATHER OF HIS PEOPLE, can unfeelingly hear of their slaughter, and composedly sleep with their blood upon his soul. Thomas Paine then began to compose a book of some 25,000 words, which he called “Common Sense.”

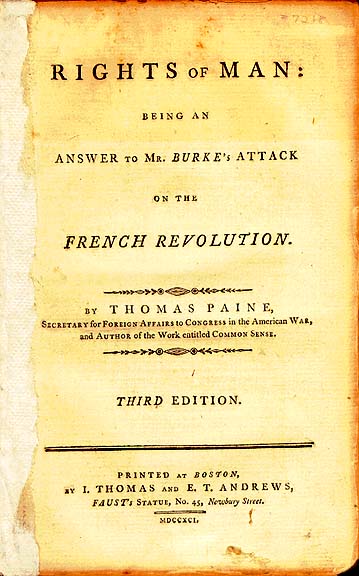

And in this book he asked Franklin, Jefferson, Washington - and indeed all of his now fellow-colonial Americans - to consider a towering concept. He asked them to consider the great ideal that America could become, if they fought against King George III’s England, and achieved their American republican independence. Tom wrote: The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. 'Tis not the affair of a city, a county, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent—of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. 'Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed-time of continental union, faith and honour. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters… O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose, not only the tyranny, but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia, and Africa, have long expelled her—Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind. This short book, from which these extracts are taken, became an immediate and astounding success. It was estimated that at least 300,000 copies were sold. And Tom Paine refused to accept any money in reward. He said: In a great affair, where the good of man is at stake, I love to work for nothing; and so fully am I under the influence of this principle, that I should lose the spirit, the pleasure, and the pride of it, were I conscious that I looked for reward. Yes… you are a better man than I am, Thomas Paine. But what he did receive for his book was the satisfaction of creating, more than any other human being, the unification of the American colonies. Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and a fair proportion of the American people, hearing Tom Paine, stopped vacillating and committed themselves to the awesome struggle of fighting the power and wealth of England. Even conservative George Washington said: The sound doctrine and unanswerable reasoning of Thomas Paine’s pamphlet is working a wonderful change in the minds of American men. An American Continental Congress was called for, and on July 4, 1776 that Congress passed their Declaration Of Independence. The English philosopher and reformer William Cobbett stated: Whoever may have actually written the Declaration Of Independence, Thomas Paine was its real author. Paine worked through his close friend Thomas Jefferson in creating that famous document. But, he suffered one tragic failure, in spite of Jefferson’s support. Tom begged the Americans to include in their Declaration a clause which would abolish slavery. But the majority of the Americans involved refused to support this humane issue. And the new nation, and particularly the black slaves, would have to wait another 85 years for Abraham Lincoln to carry out Tom Paine’s wishes by means of a horrific and cruel Civil War. And Tom Paine seriously risked his burgeoning popularity in America when he challenged his now fellow country people with the question: With what consistency, or decency they complain so loudly [against England] of attempts to enslave them, while they hold so many hundred thousands in slavery; and annually enslave many thousands more, without any pretence of authority, or claim upon them? Oh, boy! Anyway, having rallied the American colonies to unite and fight, our hero Tom unobtrusively picked up a musket and joined General George Washington’s army which was, astonishingly enough, centered here on Manhattan. And this American army was almost entirely made up of half-trained, poorly-armed volunteers. There were barely 8000 of them. And they were facing, over there on Staten Island, General Sir William Howe and his 20,000 well-armed, well-fed, and professional British army. General Howe moved and hit the Americans, and Tom Paine, out of New York. And by December 1776, on the western bank of this Delaware River, it was low ebb for General Washington and his American army. They had been beaten and beaten and were now shivering in the ice and snow, waiting for General Howe to come across this river and to demonstrate the coup de grace. General George Washington stated: Your imagination can scarce extend to a situation more distressing than mine. Our only dependence now is upon the speedy enlistment of a new army. If this fails, I think the game will be pretty well up, as, from disaffection and want of spirit and fortitude, the inhabitants, instead of resistance, are offering submission and taking protection from Gen. Howe in Jersey. But, on the other hand, Tom Paine, at night, after his soldierly duties were finished, turned to his magical pen again, and he wrote a pamphlet which he chose to call “Crisis.” Tom Paine addressed his words primarily to the freezing American soldiers: These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph… Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it. George Washington, standing with his beaten, frozen army of part-time soldiers, and virtually waiting for awful defeat, read these words of Tom Paine. And in his stiff and inhibited manner, murmured: I have a sense of the importance of Thomas Paine. And the revered General gave orders for Tom’s pamphlet to be read to his despairing men. The effect of this on their battered spirits was astounding. Many more Americans from the city and the country joined Washington’s army. And just a few days after its publication, on Christmas Eve 1776, Washington gave orders to be rowed across this Delaware River at the head of his small army, and they immediately made war on the superior British force. The American amateurs drove the British professionals out of Trenton and soundly defeated them under their leader Lord Cornwallis. It is only fair to say that, above all else, Thomas Paine’s spirit was victorious. Admiral Lord Richard Howe [brother of William], officer commanding the British fleet in American waters, began to sense a new invincible quality in the Americans who were challenging King George III’s authority, and therefore his lordship offered an amnesty to the Americans if they would submit to the British king. Tom Paine replied, on behalf of the American people: By what means, may I ask, do you expect to conquer America? If you could not effect it in the summer, when our army was less than yours, nor in the winter, when we had none, how are you to do it? In point of generalship you have been outwitted, and in point of fortitude outdone. And then the stay-maker, the corset-maker, from Norfolk England, easily lectured the famous English naval lord, and, in doing so, invented the most famous title that, perhaps, any country has ever carried. Tom Paine predicted, quote: The United States Of America! Yes, it was the very first time that those words had been articulated – ever! “The United States Of America” will sound as pompously in the world and in history as “The Kingdom Of Great Britain.” And so, after all of this monumental rallying of America, Thomas Paine on April 17, 1777 received some official American recognition. He was made a Foreign Secretary; though, many Americans opposed the appointment because of his continuing fight for the abolition of slavery, etc., etc., etc., etc. The American War Of Independence dragged on. The problem for the Americans was now largely economic. Where to get money from to buy arms and supplies? Thomas Paine, with the vision of a statesman, suggested to the American revolutionary government that emissaries should be sent to France to ask for a loan of $8 million. The American Congress agreed, and Tom went on that mission – again, receiving no salary – arriving in Paris during March 1781. King Louis XVI met the republican Paine, and they liked each other. By August Tom was back in America with two shiploads of military supplies and the balance made up of hard French cash. And also because of that mission to Paris the French army in North America moved to support Washington’s American soldiers, and these two combined armies marched toward Yorktown in Virginia and defeated the British force there under General Cornwallis. The Americans and their French allies were now clearly winning the War Of Independence. As the British army in the now United States of American capitulated and began to withdraw, Tom Paine issued another pamphlet… The times that try men's souls is now over, and the greatest and completest revolution the world ever knew gloriously and happily accomplished. Let then the world see that America can bear prosperity and that her honest virtue in time of peace is equal to her bravest virtue in time of war. Of course, Thomas Paine had made many influential and rich enemies. He had cut across the ambitions and greed of important Americans. He had fought against slavery, by and large, unsuccessfully, and he also fought successfully for the unification of the thirteen colonies – which had now become the thirteen United States Of America. Thomas said… But that which must more forcibly strike a thoughtful and penetrating mind, and which includes and renders easy all inferior concerns, is the UNION OF THE STATES. On this our great national character depends. It is this which must give us importance abroad and security at home. It is through this that we are, or can be, nationally known in the world. And the State Of New York, to its fortunate credit, recognizing Tom’s searching worth, made him a gift of this simple house. And Tom lived here, at very lengthy intervals, for the rest of his life. Thomas Paine was a man of enlightenment. Apart from the concept of universal democracy, his imagination and energy focused on science and mechanics. Now that the War For Independence was over and won, Tom became an outstanding inventor. He proposed and designed a total rethinking of bridge-building. His revolutionary bridge was made of iron, and it had one single span. His good friend Benjamin Franklin, was of course also a distinguished inventor, and these two men, both so vital and essential to the best ideals of the United States Of America, now spent much time poring over social and scientific problems. One day, here in America, these two great and good men exchanged memorable and significant words. Benjamin Franklin said, Tom, where liberty is, there is my country. Thomas Paine must have looked carefully at his old friend before he replied, truthfully, Where liberty is not, there is mine. Now that sentiment of Tom is always the sentiment of an inspired group of human beings who are everlastingly vital to our good earthly hope. It is the sentiment of Jesus Christ, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, and that sentiment seems inevitably to lead toward martyrdom, and Tom Paine was to be no exception. His spirit drove him inexorably. He packed up the model of his precious bridge and, leaving his beloved America, he sailed on the 26th of April 1787 for France, where their terrible revolution was beginning to simmer. He was now 50 years old. When Thomas Paine arrived in France, he first hastened to his friend of 10 years duration, Thomas Jefferson, who was now the American minister to the Court of King Louis XVI. And Jefferson informed Paine of the state of the impending revolution. Of course, Thomas Paine was partly the fundamental cause of that French Revolution. His book “Common Sense” and, indeed, all of his republican, democratic writings, composed over in America, had been smuggled into France in large quantities. Therefore, Tom Paine, here in Paris, at the outset of their revolution, was already a hero and was warmly accepted. The common people of France, known as the “third estate,” as against the “first” and “second estates,” representing the Church and the nobles, were demanding a democratic share in a united National Assembly of the French nation. And when the aristocracy and the clergy refused this, the French Revolution was simply inevitable. On July 14, 1789, the “third estate,” the ordinary people, raided the infamous prison, often a political prison, known as “The Bastille,” and began to pull it apart. General Lafayette, romantic French officer who had travelled to America to fight under George Washington against the British, ceremoniously and symbolically present the key of the vanquished Bastille prison to Thomas Paine for him to hand on to George Washington. And here is the key of the Bastille, hanging on a wall of George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon, here in the United States Of America. And towards the end of 1789, Thomas Jefferson left France for America. Thomas Paine was now the only American of stature left in Europe. Edmund Burke was one of the great deceivers in English history. His famous reputation was built on his well-expressed liberal sentiments. But Edmund Burke jeopardized his powerful potential for 1,500 pounds per year, which came from King George III’s treasury. You see, the anti-democratic influence here in Britain, personified by King George III, was worried that the popular revolution that had blazed across the 13 sometime British-American colonies and that had apparently sparked off the French Revolution might jump across the English Channel and engulf Britannia herself. The center of power in England was worried sick that true democracy, a democracy for all the people, would reach our British shores. So, that English power center successfully corrupted Edmund Burke to the extent that he wrote a book which upheld the French monarchy and ridiculed the motto of the French Revolution, which at that time decently pleaded for “liberty, equality, and fraternity.” And when Tom Paine heard about Burke’s composition, he crossed the English Channel with alacrity, and chanced his liberal luck there, in the very bosom of his main enemy, England. Tom read Burke’s words and considered them, and he began to write his reply. Tom Paine called this book “The Rights Of Man.”

And in this book not only did he smash Burke into the ground, where he belonged, but he also raised a banner which still braves the air above us today, that is, if we have the quality to see it – there it is, “The Rights Of Man”; and of course, Tom Paine meant also the rights of women. Tom Paine objected to Edmund Burke’s conservative concept that the King of England and the King of France’s mighty establishments were fixtures that should not be shifted. Our Tom wrote, There never did, there never will, and there never can, exist a Parliament, or any description of men, or any generation of men, in any country, possessed of the right or the power of binding and controlling posterity to the "end of time," or of commanding for ever how the world shall be governed, or who shall govern it; and therefore all such clauses, acts or declarations by which the makers of them attempt to do what they have neither the right nor the power to do, nor the power to execute, are in themselves null and void. Every age and generation must be as free to act for itself in all cases as the age and generations which preceded it. The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies. Man has no property in man; neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow. Tom then had a go at Burke on the subject of Britain’s claimed constitution: A constitution is not a thing in name only, but in fact. It has not an ideal, but a real existence; and wherever it cannot be produced in a visible form, there is none. A constitution is a thing antecedent to a government, and a government is only the creature of a constitution. The constitution of a country is not the act of its government, but of the people constituting its government. It is the body of elements, to which you can refer, and quote article by article; and which contains the principles on which the government shall be established, the manner in which it shall be organised, the powers it shall have, the mode of elections, the duration of Parliaments, or by what other name such bodies may be called; the powers which the executive part of the government shall have; and in fine, everything that relates to the complete organisation of a civil government, and the principles on which it shall act, and by which it shall be bound. A constitution, therefore, is to a government what the laws made afterwards by that government are to a court of judicature. The court of judicature does not make the laws, neither can it alter them; it only acts in conformity to the laws made: and the government is in like manner governed by the constitution. Can, then, Mr. Burke produce the English Constitution? If he cannot, we may fairly conclude that though it has been so much talked about, no such thing as a constitution exists, or ever did exist, and consequently that the people have yet a constitution to form. Mr. Burke will not, I presume, deny the position I have already advanced — namely, that governments arise either out of the people or over the people. The English Government is one of those which arose out of a conquest, and not out of society, and consequently it arose over the people; and though it has been much modified from the opportunity of circumstances since the time of William the Conqueror, the country has never yet regenerated itself, and is therefore without a constitution. And that pertains to this day. And then Thomas Paine turned to that privileged part of British government which Edmund Burke was arguing to be essential to national stability: Why then, does Mr. Burke talk of his house of peers [the House Of Lords] as the pillar of the landed interest? Were that pillar to sink into the earth, the same landed property would continue, and the same ploughing, sowing, and reaping would go on. The aristocracy are not the farmers who work the land, and raise the produce, but are the mere consumers of the rent; and when compared with the active world are the drones, a seraglio of males, who neither collect the honey nor form the hive, but exist only for lazy enjoyment. Of course, to argue democratic reason in King George III’s Britain could land you into uncomfortable trouble as Tom Paine found out; and, indeed, to argue reasonable fair play over in revolutionary France, once the ideals had got out of hand, could easily lead you to the guillotine, as Tom Paine was to find out. And even in new America, if you were constant in your reasoned idealism, as our Tom was, you could end your days as a rejected pariah, or at least a national embarrassment, as Tom Paine was to find out. In certain cases the State, the Establishment, if you were an ordinary person, a member of the “third estate,” as the French called it, the Establishment would prefer you to remain in ignorance and not to ask any awkward questions. And it would also prefer, none of us, like Tom Paine, to give any uncomfortable answers. Tom was worried about this in the eighteenth century, and some of us are worried about it today, here and now. Towards the end of his book, “The Rights Of Man, Tom Paine simply defined himself and what he stood for. He wrote, Independence is my happiness, and I view things as they are, without regard to place or person; my country is the world, and my religion is to do good. Anyway, Tom was here in London, and “The Rights Of Man” exploded over the nation. It is generally agreed that the publication of this book caused a bigger political furor than the publication of any other book of the whole history of Britain – yes, to this present day. And over 200,000 copies were sold. The British government organized, and paid money, to mobs throughout the country, to insult the name of Thomas Paine; from the top of Britain to the bottom, they arranged that “The Rights Of Man” should be burned in public; and during this year 1792 Tom Paine’s effigy was burned instead of Guy Fawkes [a treasonous insurgent against King James I, 1605] on November the 5th.

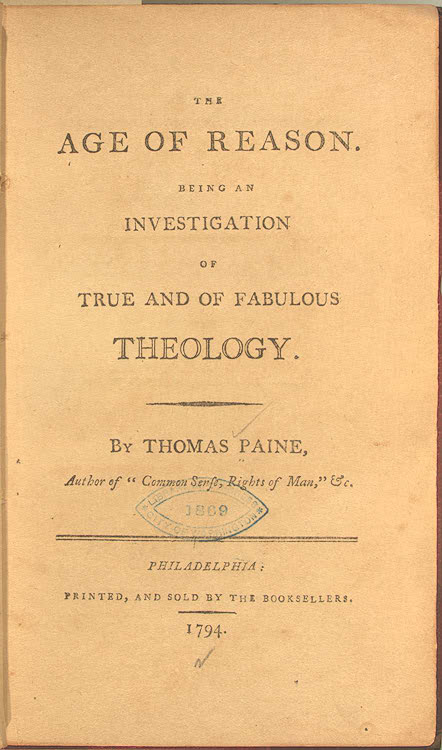

It was the measure of the British government’s fear that Tom’s simple democratic faith would overwhelm this British country of privilege. The Prime Minister, William Pitt The Younger, not a patch on his dad, incidentally, Pit The Elder, Lord Chatham, had at least a vestige of honesty when he confessed, Tom Paine is quite right. But what am I to do? As things are, if I were to encourage his opinions we should have a bloody revolution. And then Tom Paine summed up the ability of King George III and his undistinguished family: Hereditary succession is a burlesque upon monarchy. It puts it in the most ridiculous light, by presenting it as an office which any child or idiot may fill. It requires some talents to be a common mechanic; but to be a king requires only the animal figure of man- a sort of breathing automaton. This sort of superstition may last a few years more, but it cannot long resist the awakened reason and interest of man. And on the general question of hereditary principles Tom stated: An hereditary governor is as inconsistent as an hereditary author. I know not whether Homer or Euclid had sons; but I will venture an opinion that if they had, and had left their works unfinished, those sons could not have completed them. Do we need a stronger evidence of the absurdity of hereditary government than is seen in the descendants of those men, in any line of life, who once were famous? Is there scarcely an instance in which there is not a total reverse of the character? It appears as if the tide of mental faculties flowed as far as it could in certain channels, and then forsook its course, and arose in others. How irrational then is the hereditary system, which establishes channels of power, in company with which wisdom refuses to flow! By continuing this absurdity, man is perpetually in contradiction with himself; he accepts, for a king, or a chief magistrate, or a legislator, a person whom he would not elect for a constable. That did it. On May the 21st 1792 Thomas Paine was summoned to attend a Court Of the King’s Bench, and a royal proclamation was read prohibiting the sale of “The Rights Of Man.” This indictment read, Thomas Paine, being “a wicked, malicious, seditious, and ill-disposed person” who, “being greatly disaffected to our said sovereign lord the now king, and to the happy constitution and government of this kingdom,” had “most unlawfully, wickedly, seditiously, and maliciously” devised, contrived, and intended “to scandalize, traduce, and vilify the late happy revolution” (i.e., the Glorious Revolution of 1688), which had been “providentially brought about and effected under the wise and prudent conduct of His Highness William, heretofore Prince of Orange, and afterwards King of England, France, and Ireland, and the dominions thereunto belonging….” Tom Paine was alarmingly fearless. He replied to that royal proclamation and his indictment, quote: Could I have commanded circumstances with a wish, I know not of any that would have more generally promoted the progress of knowledge, than the late Proclamation, and the numerous rotten Borough and Corporation Addresses thereon. They have not only served as advertisements, but they have excited a spirit of enquiry into principles of government, and a desire to read the RIGHTS OF MAN, in places, where that spirit and that work were before unknown. The people of England, wearied and stunned with parties, and alternately deceived by each, had almost resigned the prerogative of thinking. Even curiosity had expired, and a universal langour had spread itself over the land. The opposition was visibly no other that a contest for power, whilst the mass of the nation stood torpidly by as the prize. In this hopeless state of things, the First Part of RIGHTS OF MAN made its appearance. It had to combat with a strange mixture of prejudice and indifference; it stood exposed to every species of newspaper abuse; and besides this, it had to remove the obstructions which Mr. Burke's rude and outrageous attack on the French Revolution had artfully raised. But how easily does even the most illiterate reader distinguish the spontaneous sensations of the heart, from the laboured productions of the brain. Truth, whenever it can fully appear, is a thing so naturally familiar to the mind, that an acquaintance commences at first sight. No artificial light, yet discovered, can display all the properties of day-light; so neither can the best invented fiction fill the mind with every conviction which truth begets. Then Tom dangerously attended a meeting here in London of a group called The Friends Of Liberty. He had already proposed a toast on behalf of democracy, which necessarily implied republicanism, he had raised his glass and said, To the revolution of the world, towards full democracy. Of course, there were British Home Office spies present. Tom was ever making big, powerful ruthless enemies. But he was also surrounded by the best and finest liberal spirits in Britain. Nevertheless, it does appear as an astonishing fact that after The Friends Of Liberty meeting, his chum, William Blake, whispered an awful warning – yes, William Blake, the beautiful prophet, the English visionary, whispered to Thomas Paine, You must not go home; or, if you do, you will be going to your death. Tom Paine had no wish to die in the Tower Of London, so he made a circuitous dash for France. And as the ship that was carrying him back to France entered Calais harbor, military guns fired a salute in his honor and revolutionary soldiers escorted him to the Town Hall, through the cherishing populace. In France Tom Paine was now the acknowledged inspiration to the hopes of democracy through revolution. On August the 26th 1792 the National Assembly Of France made him an honorary French citizen; and shortly afterwards he was elected as a member of the French Convention, an institution which he himself had advocated. This French invitation stated, Thomas Paine’s love for humanity, for liberty and equality, the useful works that have issued from his heart and pen, in their defense have determined our choice. And as Tom Paine took his seat, here in this National Assembly Of France, the members got to their feet and cheered. The President addressed Tom, We take you to our bosom because it becomes the French nation that has proclaimed “The Rights Of Man”… Back in Britain the government and its acolytes continued its virulent campaign against Thomas Paine. Then on December the 18th 1792 his trial began without his presence. It was held in the Court Of King’s Bench with a pensioned judge Lord Kenyon presiding, and with a picked, bribed jury. Tom wrote a hair-raising letter to the British Attorney General. These are Tom’s words: That the Government of England is as great, if not the greatest, perfection of fraud and corruption that ever took place since governments began, is what you cannot be a stranger to, unless the constant habit of seeing it has blinded your senses; but though you may not choose to see it, the people are seeing it very fast, and the progress is beyond what you may choose to believe. Is it possible that you or I can believe, or that reason can make any other man believe, that the capacity of such a man as [George III] or any of his profligate sons, is necessary to the government of a nation? I speak to you as one man ought to speak to another; and I know also that I speak what other people are beginning to think. That you cannot obtain a verdict (and if you do, it will signify nothing) without packing a jury (and we both know that such tricks are practised), is what I have very good reason to believe. I have gone into coffee-houses, and places where I was unknown, on purpose to learn the currency of opinion, and I never yet saw any company of twelve men that condemned the book; but I have often found a greater number than twelve approving it, and this I think is a fair way of collecting the natural currency of opinion. The result of that trial was starkly obvious. Tom Paine was found guilty and proclaimed an outlaw. Meanwhile, over here in France, on the 22nd of September 1792 the monarchy, the concept of a royal family, was abolished by the revolutionary government. Of course, Tom Paine being a sound republican approved of this measure, but also there was political pressure building up to execute King Louis XVI, and Tom did not approve of that violent idea. And already it was becoming clear that anyone who opposed the extremists of the revolution – known as Jacobins – over any matter, leave alone the execution of their proud and miserable king, was in lethal danger. It was Tom Paine, the inspirer of American and French republicanism, who had the awesome nerve to stand up in this National Assembly Of France and address those extremists – Robespierre [and company]. On the subject of mercy and the fate of their sometime king, these are Tom Paine’s words: As France has been the first of European nations to abolish royalty, let us also be the first to abolish the punishment of death. I vote for the perpetual banishment of [King Louis XVI]. [Robespierre’s company replied:] I submit that Thomas Paine is incompetent to vote on this question. He’s a Quaker. His mind is contracted by the narrow principles of his Christian religion. He’s incapable of the liberality which is necessary for condemning men to death. [Tom Paine replied:] My language has always been that of liberty and humanity, and I know that nothing so exalts a nation as the union of these two principles. [Robespierre’s company replied:] Frenchmen are mad to allow foreigners to live among them. They should cut off their ears, let them bleed for a few days, and then cut off their heads. The Jacobins prevailed, and Louis XVI the sometime King Of France was guillotined and a reign of terror erupted over France… Thomas Paine made a last desperate appeal to the Jacobins… I am distressed to see so little attention paid to moral principles. It is this that injures the character of our revolution and discourages the progress of liberty all over the world. Most of the acquaintances I have at the Convention are on the death list. And I know that there are not better men and better patriots than they. Thomas Paine waited for his own nemesis. He quietly helped those who awaited death for political reasons, and he remained in Paris as the leader of the old democratic hope. And it was during this deadly period that Paine began to ponder another book which he called “The Age Of Reason.”

While waiting for the servants of the guillotine, he wrote: It has been my intention, for several years past, to publish my thoughts upon religion. I am well aware of the difficulties that attend the subject, and from that consideration, had reserved it to a more advanced period of life. I intended it to be the last offering I should make to my fellow-citizens of all nations, and that at a time when the purity of the motive that induced me to it, could not admit of a question, even by those who might disapprove the work. The circumstance that has now taken place in France of the total abolition of the whole national order of priesthood, and of everything appertaining to compulsive systems of religion, and compulsive articles of faith, has not only precipitated my intention, but rendered a work of this kind exceedingly necessary, lest in the general wreck of superstition, of false systems of government, and false theology, we lose sight of morality, of humanity, and of the theology that is true. As several of my colleagues and others of my fellow-citizens of France have given me the example of making their voluntary and individual profession of faith, I also will make mine; and I do this with all that sincerity and frankness with which the mind of man communicates with itself. I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life. I believe in the equality of man; and I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavoring to make our fellow-creatures happy. But, lest it should be supposed that I believe in many other things in addition to these, I shall, in the progress of this work, declare the things I do not believe, and my reasons for not believing them. I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church. All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit. I do not mean by this declaration to condemn those who believe otherwise; they have the same right to their belief as I have to mine. But it is necessary to the happiness of man, that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving; it consists in professing to believe what he does not believe. It is impossible to calculate the moral mischief, if I may so express it, that mental lying has produced in society. When a man has so far corrupted and prostituted the chastity of his mind, as to subscribe his professional belief to things he does not believe, he has prepared himself for the commission of every other crime. He takes up the trade of a priest for the sake of gain, and in order to qualify himself for that trade, he begins with a perjury. Can we conceive anything more destructive to morality than this? Tom then turned and considered specifically Jesus Christ, and how the Christian church has often misused him: The church has set up a system of religion very contradictory to the character of the person whose name it bears. It has set up a religion of pomp and of revenue, in pretended imitation of a person whose life was humility and poverty… That such a person as Jesus Christ existed, and that he was crucified, which was the mode of execution at that day, are historical relations strictly within the limits of probability. He preached most excellent morality and the equality of man; but he preached also against the corruptions and avarice of the Jewish priests, and this brought upon him the hatred and vengeance of the whole order of priesthood. The accusation which those priests brought against him, was that of sedition and conspiracy against the Roman government, to which the Jews were then subject and tributary; and it is not improbable that the Roman government might have some secret apprehension of the effects of his doctrine as well as the Jewish priests ; neither is it improbable that Jesus Christ had in contemplation the delivery of the Jewish nation from the bondage of the Romans. Between the two, however, the virtuous Reformer and Revolutionist lost his life. It is upon this plain narrative of facts, together with another case I am going to mention, that the Christian mythologists, calling themselves the Christian Church, have erected their fable, which for absurdity and extravagance is not exceeded by anything that is to be found in the mythology of the ancients… But some perhaps will say are we to have no word of God no revelation? I answer, Yes; there is a word of God, there is a revelation. THE WORD OF GOD is THE CREATION WE BEHOLD, and it is in this word which no human invention can counterfeit or alter, that God speaketh universally to man.

Just six hours after Tom had finished this book, the police of the reign of terror entered his room, arrested him, and conveyed him to the Luxembourg Prison [in Paris] to await the official knife. The Luxembourg Prison was a death camp. Thomas Paine recorded that 160 prisoners were guillotined on a single day. And the only reason that Tom remained alive in this cell was that Robespierre, personifying the terror of the French Revolution, was afraid of offending George Washington, who had now become the personification of The United States Of America.

a black mark on George Washington's record Tom Paine waited for the all-powerful, near-deified Washington to speak on his behalf and thereby secure his freedom; and the awful, disgusting fact is, that George Washington, Tom Paine’s old colleague and friend, failed to say one single word, and he failed for the worst of possible reasons. He refused to speak for political reasons. George Washington, on behalf of The United States Of America, now wanted to achieve a closer, friendlier relationship with Britain. America now wanted help and cooperation from Britain. And George Washington knew that Tom Paine who was awaiting death in the Luxembourg Prison in Paris was now the British government’s public enemy number one. Tom Paine was Britain’s best known outlaw, and therefore Tom’s life was expendable. Tom Paine struggled with this terrible reality. He couldn’t believe that his old friend by whose side he had stood at Valley Forge when the American Revolutionary Army had seemed defeated was now turning his back on his honorable suffering. When Tom Paine realized that truth about George Washington of the newly born United States Of America, that realization injected a bitterness into his soul that never completely left until he died. Tom Paine wrote a letter to George Washington: PARIS, February 22, I795. George Washington never replied to this cri de coeur. Robespierre, noting George Washington’s silence, decided that he could safely kill Thomas Paine, the dedicated republican who had dared to plead for the life of the ex-King Of France: I demand that a writ accusing Thomas Paine be issued in the interests of America and of France. The stupendous irony of that statement is nothing less than evil. Expedient politicians should bear in mind that they often hold the Devil’s hand. But Robespierre failed to kill Thomas Paine because before he could achieve it the anarchy that was now France guillotined him. It was James Monroe, who was to become America’s fifth President, worked for and finally secured Tom Paine’s release from the Luxembourg Prison… [In his letter, dated September 18th, Monroe wrote:] "It is unnecessary for me to tell you how much all your countrymen, I speak of the great mass of the people, are interested in your welfare… You are considered by them, as not only having rendered important services in your own revolution, but as being on a more extensive scale, the friend of human rights, and a distinguished and able advocate in favor of public liberty. To the welfare of Thomas Paine the Americans are not and cannot be indifferent. To liberate you, will be an object of my endeavors…" On November 6, 1794 Thomas Paine was set free. He had suffered for 11 months in daily expectation of death by guillotine. James Monroe took care of Paine on his release in Paris but was shocked at his appalling physical condition. Monroe presumed that the hero was dying. He said, The prospect is now that he will not be able to hold out for more than a month or two at the furthest. I shall certainly pay the utmost attention to this gentleman, as he is one of those whose merits in our American Revolution were most distinguished. Of course, Tom Paine was a tough bird, and he didn’t die – here in Paris. Tom was now in his late fifties, his greatest remaining ambition was to return to The United States Of America, and there to live out his remaining years. But it was dangerous for him to sail westward. British warships patrolled the coast of France and the Royal Navy was looking for the feared, democratic outlaw. Napoleon Bonaparte was now beginning to halt the anarchy of revolutionary France. Tom Paine, as ever, was poor and lived in simple conditions. One day during the autumn of 1797 there was a knock on Tom’s door, and there, without any prior warning, was the future Emperor Of France. And the young General Napoleon Bonaparte, as he then was, immediately came to the point of his visit: Monsieur Paine, I am greatly influenced by your book “The Rights Of Man.” I sleep with that book every night under my pillow. A statue of gold should be erected to you in every city in the universe. And that was Napoleon’s assessment, for whatever it is worth, of the English artisan from Thetford in Norfolk. In the year 1801 Thomas Jefferson became the third President of The United States Of America. The new President wrote to Tom in Paris offering him a passage back to America on an American warship. Jefferson’s letter continued: I’m in hopes you will find The United States Of America generally to sentiments worthy of former times. And in those times it was your glory to have steadily labored, and with as much effect as any man living. You may live to continue your useful labors and to reap the thankfulness of nations, that is my sincere prayer. British warships had ceased patrolling the French coast because their war with France had ended. And Thomas Paine sailed for his American republic. He landed in Baltimore on October 30th, 1801. He had been away striving for a decent French republic for 15 years. In spite of Thomas Jefferson’s hope that America had returned generally to sentiments worthy of former times – it was not so. The national emphasis in America had moved rapidly from idealism to materialism. And of course our Tom had not shifted one inch from his concept of “The Rights Of Man” and of women. He landed in America and with him he was carrying America’s Paine-ful conscience. Tom reiterated the vital importance of abolishing slavery; of the rights of all grown persons to vote; he argued that workers must have the right to form trade unions; and he continued to harp on behalf of penalized married women. Therefore, our dear hero was not received in America with a spirit that reflected Jefferson’s hopes, to reap the reward of the thankfulness of nations. Indeed, the tragic truth is that Thomas Paine was reviled loudly and publicly. The stick that Puritan America used against Thomas Paine was his attack in “The Age Of Reason” on the superstitious passages contained in the Bible, and they ignored his deep respect for the historical Jesus Christ. They called Thomas Paine an atheist, godless, which he was patently not. However, the finer minds held close to him. President Jefferson openly invited the outcast conscience of America to stay with him… at the White House. The two friends, one held so high, and the other, held so low, sat in front of the Presidential fire and discussed the hopes of humankind. Thomas Paine urged the President to buy Louisiana from the French, which Jefferson did – the biggest bargain in the entire history of America, and put forward by Tom in his very serious poverty, while he was being grossly insulted by a large part of commercial America. Around the Presidential fire, sick old Tom Paine nagged Thomas Jefferson to use his growing international influence to form the United Nations Of The World. Tom called this last great dream, … an Association Of Nations, an end of war, a beginning of international love. Who was truly close to the prayers of Jesus Christ? – churches of every denomination, or Tom Paine? To President Jefferson’s eternal credit, he walked through the city of Washington, arm in arm, with a weak, shabby, old man, who had conceived “The Rights Of Man” and “The Age Of Reason.” And that act, on the President’s part, did him no political good, whatsoever. The State Of New York had given Tom this house in New Rochelle. He finally retired here, to die, in some bewilderment at the sad ways of humanity. He became very sick. His imprisonment in Paris had crushed his constitution. They say Tom sat very still looking straight ahead, not moving. Very few people now dared to even speak to the politically dangerous patriot. American mothers would threaten their children with, The Devil and Tom Paine will catch you!

On election day in the year 1806, the inspired hero of the American Revolution, the man who had whispered the words of the American Constitution, the man who before anyone else had created the worded banner of The United States Of America, the man who would become the inspiration of Abraham Lincoln, moved painfully out of this house to place his democratic republican vote. And when he arrived at the voting place the wretched official who was in charge informed the hero that he was not entitled to vote: You are not an American citizen; otherwise would not our great George Washington have secured your release from your death-cell in Paris? Before Thomas Paine died, he asked himself the question, the biggest question that we should all ask ourselves, and Tom was able to answer himself, I have lived an honest and useful life to mankind; my time has been spent in doing good, and I die in perfect composure and resignation to the will of my creator, God. Dated the eighteenth day of January, in the year one thousand eight hundred and nine; and I have also signed my name to the other sheet of this will, in testimony of its being part thereof. Then Tom considered where exactly his body should be buried. He composed a letter, I know not if the Society of people called Quakers, admit a person to be buried in their burying ground, who does not belong to their Society, but if they do, or will admit me, I would prefer being buried there; my father belonged to that profession, and I was partly brought up in it. But if it is not consistent with their rules to do this, I desire to be buried on my own farm at New Rochelle. The place where I am to be buried, to be a square of twelve feet, to be enclosed with rows of trees, and a stone or post and rail fence, with a headstone with my name and age engraved upon it, author of "Common Sense." The Quakers refused Tom Paine’s request. He was buried on the 8th of June 1809 here in New Rochelle of the State Of New York of The United States Of America – which country, I submit, he had done more for in terms of true quality than any other human being. He was buried in the orchard of his home. Few people were present: two black Americans, one white American, and a French woman, whom Tom had rescued from France, and towards whom he had long been platonically very kind. Her name was Madame Bonneville. And she had with her, at the graveside, a son. As the earth was shoveled onto Tom’s coffin, Madame Bonneville suffered a compulsion to speak. And she has remembered a pitiful truth: I placed myself at the east end of the grave, and I said to my son, Benjamin, "Stand ye there, at the other end, as a witness for grateful America." I looked around me, and beholding the very small group of spectators, I exclaimed, as the earth was tumbled into the grave, “Oh, Mister Paine, my son stands there as a testament to the gratitude of America, and I stand here for France.” This was the funeral ceremony, as I remember it, of this great philosopher.

|

||||

|

|