|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Emily Dickinson This Consciousness that is aware (#822)

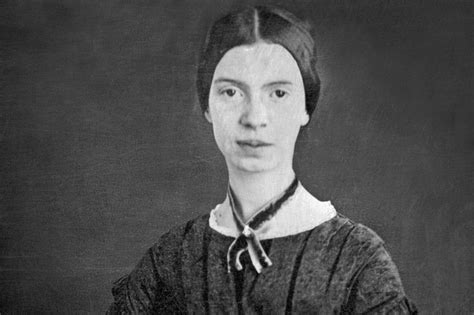

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

This Consciousness that is aware Is traversing the interval How adequate unto itself Adventure most unto itself

In # 822, Emily Dickinson describes experience as an experiment in consciousness. Each of us, as a consciousness, is aware of environment (‘the Sun’), our fellow species members (‘Neighbors’). We share this basic level of awareness with much of the living world. A much rarer awareness, probably existing only in some vertebrates, is self-awareness (‘itself’ is used five times in this poem of 67 words), and awareness of death. Beyond self-awareness, we have a capability for mental experimentation that is only possible with language, and is thus probably unique among organisms. Here is how Daniel Dennett illustrates this capacity:

Using scientific terms, Dickinson describes Experience, that interval we traverse, as an experiment to test the adequacy of our mind’s properties. But unlike science, the results we find may be incommunicable. Science is a community activity – findings must be communicated and accepted to count as discoveries. The findings of an isolated consciousness may be incommunicable, because they result from an adventure purely within ourselves, attended by the “single Hound” of our own identities. Poetry is a relatively condensed form of expression, but even by the standards of poetry Emily Dickinson’s poems are gnomic, rivaling the expressive density of T’ang Dynasty verse. In this set of four quatrains, arranged in a hymn-like rhythm of alternating four-beat and three-beat lines, she communicates the incommunicability of experience.

from https://www.academia.edu/5878449/This_Consciousness_ that_is_Aware_Emily_Dickinson_s_Phenomenology_as_Consolation Some years ago, I taught a community education seminar at The Emily Dickinson Homestead called “Of Consciousness, her awful Mate" that focused exclusively on Dickinson’s phenomenological poems – that is, the poems in which Dickinson attempts to describe the anatomy of consciousness. These poems had always appealed to me as metaphysical contortionist acts, efforts to use language to enable the soul to see what it looks like with its eyes closed. But the subject soon lost its theoretical cast when one of the participants, an octogenarian, reported that her husband had died shortly after the first meeting. She herself was so frail it was hard to imagine how she could bear the weight of her loss. I suggested, with what I hoped was tact, that perhaps she didn’t feel up to coming to class. But she insisted on attending. She and her husband had been reading the poems I’d assigned virtually up to the moment of his death, she told us. Her husband had loved them, and they both had felt that Dickinson’s words were easing the incomprehensible transition as his life slipped through their hands. Even as I welcomed her continued participation, I couldn’t help but wonder how Dickinson’s poems had helped them. While Dickinson certainly participated in her era’s sentiment-soaked approach to death and mourning, in the selection of poems I had assigned, her attitude is detached, almost sardonic. For example, take the first stanza of “A Solemn thing within the Soul”, a poem that suspends awareness of mortality between the calipers of phenomenological examination: A Solemn thing within the Soul The moment of awareness this poem describes – the “Solemn thing” that is recognition of one’s own mortality – is normally fraught with feeling. Dickinson drains away such personal elements, offering a dispassionate portrayal purged of any characteristics that might identify “the Soul” with one individual or another. Such abstracting, generalizing effects are built into phenomenology. When consciousness becomes the object of its own analytical attention, the reticent, enigmatic recesses we normally think of as our most Dickinson’s mappings of this model Soul magnify our deepest, most delicate sensations, making them visible to us, enabling us to reflect on and articulate them. But in doing so, they depersonalize those sensations, presenting as categorizable “things” what we normally experience as idiosyncratic gestalts of feeling. In this sense, phenomenological “Consciousness” is indeed an “awful mate” for “the Soul.” Dickinson never tired of turning the cold eye of phenomenology on our most intimate states of psychic distress, such as the ripening shudder of mortality. In fact, Dickinson portrays detached self-awareness as a normal, or at least unavoidable, response to anguish, grief and death. For example, in “After great pain, a formal feeling comes” (Fr372), the observing consciousness circulates like a visitor at a wake: “The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs – / The stiff Heart questions `was it He, that bore’, / And yesterday, or Centuries before’?” ... But for Dickinson, phenomenological detachment in the face of “great pain” also represents a sort of triumph, consciousness’ resistance to This Consciousness that is aware As this poem suggests, for Dickinson, “Death” not only doesn’t blot out “Consciousness” – it heightens it. Even as the Soul “traverses” this “most profound experiment,” consciousness continues to record and reflect, examining death with the scientific detachment that the word “experiment” suggests. But death is only the medium, not the subject of this experiment, a sort of acid test that reveals the ultimate “adequacy” which keeps the Soul under its phenomenological microscope throughout and apparently after the dying process, transforming every throe into an assay of its own “properties.” Indeed, rather than extinguishing “This Consciousness that is Aware,” Death demonstrates its ineradicable “continuance.” Dickinson often presents this “continuance” of phenomenological awareness as “a tragic fact” – the Soul is “condemned to be” its own “Adventure,” apparently for all eternity. But as the poem’s confident tone suggests, this undying self-awareness also represents, in radically secularized terms, the Soul’s victory over Death, its relegation of Death to one item among the many of which “Consciousness … is aware.” Which is to say that for Dickinson, phenomenology is consolation – perhaps the only consolation consciousness can offer or receive in a modernized world of faltering faith where “God’s Right Hand” is “amputated” and “God cannot be found” (Fr1581). This insistence, bleak as it is, may have comforted my student and her husband as they watched together over the failing of his senses, their vigil lit by the medical machinery that measures the moment-by-moment “ripening of the soul” in terms of deterioration of pulse and breath. To those traversing it, Dickinson’s unsentimental charting of the psychic terrain between the moment that the soul “feels itself get ripe” and the moment of “hearing … Being drop” offers a consoling image of consciousness’ independence of the tragic gravity of death. But as “This Consciousness that is aware” and other poems suggest, for “This Consciousness that is aware” emphasizes the tendency of consciousness toward self-enclosed isolation...

1775 poems

|

||

|

|