|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Quantum Mechanics

return to "Quantum Mechanics" main-page

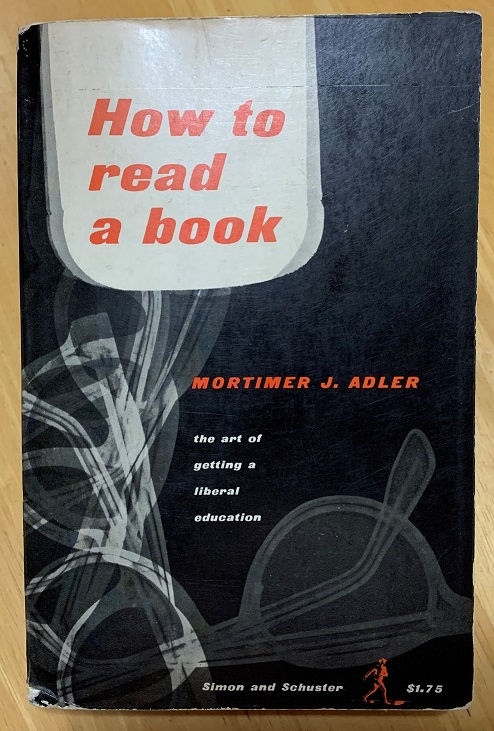

This is one of my prized possessions, a 1940 edition of Dr. Mortimer Adler’s “How To Read A Book.” (If you get a copy, make sure it’s the original 1940 work. Adler’s associates later produced a revision, with the same title, but made a hash of it. I once owned many thousands of books, but, as it became too much to manage, I later retained only a few. I kept this one.)

How does one study Quantum Mechanics? The same way one would study any subject - learning the vocabulary of the field which introduces basic concepts (see "Editor's Last Word"). Before we rush off to re-invent the wheel, we need to discover what's already been won. Adler’s book offers particular discussion on how to read the classics, what he called “the great books of the Western world.” The title disarms us, seems innocuous: “How To Read A Book.” “Well,” the response might be, “I know how to read. I learned that in first grade.” So we say. But Adler points out that very few have truly mastered, or even begun to negotiate, this art. His first sentence of the book jars us with, “This is a book for readers who cannot read. That may sound rude, but I do not mean to be. It may sound like a contradiction, but it is not.” What is the real problem here for “readers who cannot read”? The “great books” are notorious for being difficult to understand. Why is this? A review of many of them reveals prose constructed, in the main, with ordinary words that any “reader” would understand. So why the bad rep for “hard to understand”? Famous case in point: the Bible, one of the Western world’s “great books,” is read by many; so-called “read.” By this I mean, if a hundred people read the Bible, we’re likely to meet with a hundred different interpretations. Why is this? Adler helps us to understand that reading, in any valid sense, must take us to the original intent of the author. But almost no “reader” does this. Instead, we find a great deal of eisegesis. The Greek word “eis” means “in” or “into”; and “gesis” is part of a Greek word which signifies “explain” or “interpret.” eisegesis is a self-deception, seeing something that isn't there So what we have here with eisegesis is not reading in any meaningful way, such that, the reader is attempting to discern the original message of the author; but, instead, eisegesis is a “reading into” the text of what one wants to see, a message that isn’t there; an injecting of private opinion and personal agenda. All this subjectivity is what disingenuously passes for “reading.” It's a Rorschach inkblot test, seeing what we want to see in the squiggly lines. And, in the case of the Bible, eisegesis becomes proximate cause for today’s many tens of thousands of religious sects, all claiming to be “Bible believing” and basing their “one true doctrines” on "infallible" holy writ. But it’s not just the Bible that get’s manhandled this way. This butchering of the text happens anytime a document wields potential power-and-control over people. Look at how the “Declaration Of Independence” and the “U.S. Constitution” are made to express whatever the Dear Leader of the moment wants it to say. In the hands of the totalitarian "readers", the revered foundational documents of America become something Orwellian, straight from the Ministry Of Truth. But eisegesis also occurs on an individual level. If the so-called reader feels threatened by a document, threatened in terms of enflaming the fear of death, or fears of not finding happiness or pleasure, or any other basic fear, then the unenlightened “reader” will “read into” the text whatever it needs to provide some measure of support for one’s egocentric agenda. All of this is an old story, and we’ve discussed these issues in other Word Gems writings. However… What does this have to do with studying Quantum Mechanics? Scientists are human beings after all. And they are not immune from the existential fears of death, the afterlife, life’s meaning, and related issues. We spoke of this in the report on biological evolution. Quantum mechanics (QM) is not just a take-it-or-leave-it subject, not just a dry topic of dispassionate interest only to techno-geeks. QM bristles with overtones of an underlying meaning of reality and nature. As such, existential fears, overtly or subliminally, are ignited in its investigation. Materialists treat QM as a kind of quasi-religion, and in so doing, will “read into” the QM findings what they need to see in order to maintain their metaparadigm of life and the universe. Rupert Sheldrake, 2008 interview comment: “These are mainly people who are committed to a kind of militant/atheist worldview. As far as they are concerned, if you allow any psychic phenomena to occur you are leaving a door open a crack and . . . within seconds you could have God back again and, even worse, the Pope. So, I think, for them, it’s almost like a kind of religious struggle. It’s like a crusade.” All of this means that it’s extremely difficult to get a straight story on the research findings of QM – it’s like the numerous religious sects. As we’ve seen in the field of afterlife research, materialistic scientist will purposefully skew the data and misrepresent whatever they fear; fear, in the sense of challenging the materialistic world view. What we can learn from Adler’s “How To Read A Book”? I’ve stated that studying QM, in principle, is no different than any other worthy field of research. And when we enter any new field of study, the honest investigator will adhere to basic rules of evidence: Define terms: The first step is to learn the lingo of the new field. You can’t even talk about the big ideas of the subject unless you know the vocabulary, the basic concepts. This is elementary, but few do this and, instead, jump right to “reading into” the text. What is the original author’s meaning when he first used the technical terms? Dictionaries are of limited value here. A word might have a dozen different dictionary meanings, but none of that is dispositive for us. What we want to know is, what did the original researcher, the one writing the scientific report concerning the early experiments, mean when he or she used the term? How does the term change, given the flow of the author’s argument? Meanings are slippery. It may begin as one thing, but, as the author-researcher compiles data, the meaning might easily shift. Keep an eye on context, what comes before and after. All this will get us started with a study of QM. We need to take notes. Be prepared for several years of investigation. We need to build from the known to the unknown. This is not easy, especially when so many of the reports and videos are designed, not to make clear but, to mystify and befuddle you, to create stumbling blocks, in order for the egos-in-charge to protect their metaparadigm under attack – that is, if you begin to think you know something about the subject, then you'll be challenging their materialistic view.

|

||

|

|