|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

|||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Repression

"Sometimes you may not know that you are attached to something, which is to say, identified, until you lose it or there is the threat of loss. If you then become upset, anxious, and so on, it means you are attached. If you are aware that you are identified with a thing, the identification is no longer total. 'I am the awareness that is aware that there is attachment.' That’s the beginning of the transformation of consciousness." Eckhart Tolle, The New Earth

Editor's 1-Minute Essay: Repression Editor's Essay: What Men Really Want

“It isn't normal to know what we want. It is a rare and difficult psychological achievement.” Abraham H. Maslow

Freud's discovery of repression ranks among the great achievements of the twentieth century. But how can we be certain shadowy repression exists when there seem to be no outward signs? Psychologists inform us that it's betrayed by subtle clues detected by monitoring devices measuring skin temperature, pupil dilation, increased heart-rate, and the like. But we really don't need fancy electronic equipment. As Tolle, above, mentions, hidden attachments, which is to say, repressed information concerning identification, might suddenly be revealed by unexpected anger, defensiveness, and perceived threat. This phenomenon is common knowledge to all, referred to as "hitting the hot-button" of someone. Coming to awareness of one's repressions, a deep house-cleaning, is vital to anyone seeking wholeness and mature spirituality. Below you'll find extracts from the works of four notable thinkers in this field. Sigmund Freud: invented psychoanalysis and the term "repression"; discusses how people hide from a harsh reality, seeking refuge from their repressed fears of death in orthodox religion; how dreams reveal what's going on below. Norman O. Brown: clarifies definitions of repression; explains how our thwarted desires seek shelter underground and never die; how repression is pandemic, afflicts all, all the time. Ernest Becker: focuses on the great and central repressed element of every human heart, the fear of death; how this "worm at the core," as William James called it, subtly influences our actions and thoughts on many levels of being. Eric Hoffer: famous for his writings on the psychology of cultish mass movements, he dissects this specimen in autopsy to reveal a repressed self-loathing, the sense of "spoiled self," an evasion of personal responsibility. After reviewing the information below, I invite you to read my "1-minute essay" as synthesis, a personal statement.

Sigmund Freud: Civilization and Its Discontents and other works “Life, as we find it, is too hard for us; it brings us too many pains, disappointments and impossible tasks. In order to bear it we cannot dispense with palliative measures... There are perhaps three such measures: powerful deflections, which cause us to make light of our misery; substitutive satisfactions, which diminish it; and intoxicating substances, which make us insensible to it.” Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents “Where the questions of religion are concerned people are guilty of every possible kind of insincerity and intellectual misdemeanor.” Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion “We are never so defenseless against suffering as when we love.” Sigmund Freud “Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways.” Sigmund Freud “Out of your vulnerabilities will come your strength.” Sigmund Freud “He that has eyes to see and ears to hear may convince himself that no mortal can keep a secret. If his lips are silent, he chatters with his fingertips; betrayal oozes out of him at every pore.” Sigmund Freud, Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis “In so doing, the idea forces itself upon him that religion is comparable to a childhood neurosis, and he is optimistic enough to suppose that mankind will surmount this neurotic phase, just as so many children grow out of their similar neurosis." Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion “It is impossible to escape the impression that people commonly use false standards of measurement — that they seek power, success and wealth for themselves and admire them in others, and that they underestimate what is of true value in life.” Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents “Where does a thought go when it's forgotten?” Sigmund Freud “Whoever loves becomes humble. Those who love have, so to speak, pawned a part of their narcissism.” Sigmund Freud “Religion is a system of wishful illusions together with a disavowal of reality, such as we find nowhere else but in a state of blissful hallucinatory confusion. Religion's eleventh commandment is "Thou shalt not question." Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion “Human beings are funny. They long to be with the person they love but refuse to admit openly. Some are afraid to show even the slightest sign of affection because of fear. Fear that their feelings may not be recognized, or even worst, returned. But one thing about human beings puzzles me the most is their conscious effort to be connected with the object of their affection even if it kills them slowly within.” Sigmund Freud “The virtuous man contents himself with dreaming that which the wicked man does in actual life.” Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams “It is that we are never so defenseless against suffering as when we love, never no helplessly unhappy as when we have lost our loved object of its love.” Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents “When making a decision of minor importance, I have always found it advantageous to consider all the pros and cons. In vital matters, however, such as the choice of a mate or a profession, the decision should come from the unconscious, from somewhere within ourselves. In the important decisions of personal life, we should be governed, I think, by the deep inner needs of our nature.” Sigmund Freud “Neurotics complain of their illness, but they make the most of it, and when it comes to taking it away from them they will defend it like a lioness her young.” Sigmund Freud “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now they are content with burning my books." Sigmund Freud “A man should not strive to eliminate his complexes but to get into accord with them: they are legitimately what directs his conduct in the world.” Sigmund Freud “Properly speaking, the unconscious is the real psychic; its inner nature is just as unknown to us as the reality of the external world, and it is just as imperfectly reported to us through the data of consciousness as is the external world through the indications of our sensory organs.” Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams “Dreams are the royal road to the unconscious.” Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams “Illusions commend themselves to us because they save us pain and allow us to enjoy pleasure instead. We must therefore accept it without complaint when they sometimes collide with a bit of reality against which they are dashed to pieces.” Sigmund Freud, Reflections on War and Death “Men are strong so long as they represent a strong idea; they become powerless when they oppose it.” Sigmund Freud “… public self is a conditioned construct of the inner psychological self.” Sigmund Freud “Instinct of love toward an object demands a mastery to obtain it, and if a person feels they can't control the object or feel threatened by it, they act negatively toward it.” Sigmund Freud “Thus I must contradict you when you go on to argue that men are completely unable to do without the consolation of the religious illusion, that without it they could not bear the troubles of life and the cruelties of reality. That is true, certainly, of the men into whom you have instilled the sweet -- or bitter-sweet -- poison from childhood onwards. But what of the other men, who have been sensibly brought up? Perhaps those who do not suffer from the neurosis will need no intoxicant to deaden it. They will, it is true, find themselves in a difficult situation. They will have to admit to themselves the full extent of their helplessness and their insignificance in the machinery of the universe; they can no longer be the centre of creation, no longer the object of tender care on the part of a beneficent Providence. They will be in the same position as a child who has left the parental house where he was so warm and comfortable. But surely infantilism is destined to be surmounted. Men cannot remain children for ever; they must in the end go out into 'hostile life'. We may call this 'education to reality. Need I confess to you that the whole purpose of my book is to point out the necessity for this forward step?” Sigmund Freud, The Future of an Illusion “Neurosis is the inability to tolerate ambiguity.” Sigmund Freud “How bold one gets when one is sure of being loved.” Sigmund Freud “We are threatened with suffering from three directions: from our body, which is doomed to decay..., from the external world which may rage against us with overwhelming and merciless force of destruction, and finally from our relations with other men... This last source is perhaps more painful to use than any other.” Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents “The more perfect a person is on the outside, the more demons they have on the inside.” Sigmund Freud “I can imagine that the oceanic feeling could become connected with religion later on. That feeling of oneness with the universe which is its ideational content sounds very like a first attempt at the consolations of religion, like another way taken by the ego of denying the dangers it sees threatening it in the external world.” Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents “All neurotics, and many others besides, take exception to the fact that 'inter urinas et faeces nascimur” [“born between urine and feces,” reminders of one's creatureliness, which lead us to the fear of death]. Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents “Dreams are never concerned with trivia.” Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams “The weakling and the neurotic attached to his neurosis are not anxious to turn such a powerful searchlight upon the dark corners of their psychology.” Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams “And, finally, groups have never thirsted after truth. They demand illusions, and cannot do without them. They constantly give what is unreal precedence over what is real; they are almost as strongly influenced by what is untrue as by what is true. They have an evident tendency not to distinguish between the two.” Sigmund Freud, Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego “Everyone of us who can look back over a longer or shorter life experience will probably say that he might have spared himself many disappointments and painful surprises if he had found the courage and decision to interpret as omens the little mistakes which he made in his intercourse with people, and to consider them as indications of the intentions which were still being kept secret." Sigmund Freud, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis “Dreaming, in short, is one of the devices we employ to circumvent repression, one of the main methods of what may be called indirect representation in the mind.” Sigmund Freud, A Case of Hysteria: Dora “The patient cannot remember the whole of what is repressed in him, and what he cannot remember may be precisely the essential part of it. He is obliged to repeat the repressed material as a contemporary experience instead of remembering it as something in the past.” Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle “Dreams may be thus stated: They are concealed realizations of repressed desires.” Sigmund Freud, Dream Psychology: Psychoanalysis for Beginners “Dreams tell us many an unpleasant biological truth about ourselves and only very free minds can thrive on such a diet. Self-deception is a plant which withers fast in the pellucid atmosphere of dream investigation.” Sigmund Freud, Dream Psychology: Psychoanalysis for Beginners

Norman O. Brown: Life Against Death When our eyes are opened, and the fig leaf no longer conceals our nakedness, our present situation is experienced in its full concrete actuality as a tragic crisis. … it begins to be apparent that mankind, in all its restless striving and progress, has no idea of what it really wants. Freud was right: our real desires are unconscious. There is one word which, if we only understand it, is the key to Freud’s thought. That word is ‘repression.’ The whole edifice of psychoanalysis, Freud said, is built upon the theory of repression. … the essence of society is repression of the individual, and the essence of the individual is repression of himself. [Dreams, neurotic symptoms, the Freudian-errors of everyday life] have meaning. Since the purport of these purposive expressions is generally unknown to the person whose purpose they express, Freud is driven to embrace the paradox that there are, in a human being, purposes of which he knows nothing, involuntary purposes, or … “unconscious ideas.” … Freud can thus define psychoanalysis as “nothing more than the discovery of the unconscious in mental life. … some unconscious ideas in a human being are incapable of becoming conscious to him in the ordinary way, because they are strenuously disowned and resisted by the conscious self. From this point of view Freud can say that “the whole of psychoanalytic theory is in fact built up on the perception of the resistance exerted by the patient when we try to make him conscious of his unconscious.” The dynamic between the unconscious and the conscious is one of conflict… The realm of the unconscious is established in the individual when he refuses to admit into his conscious life a purpose or desire which he has, and in doing so establishes in himself a psychic force opposed to his own idea. This rejection by the individual of a purpose or idea, which nevertheless remains his, is repression. “The essence of repression lies simply in the function of rejecting or keeping something out of the conscious.” Stated in more general terms, the essence of repression lies in the refusal of the human being to recognize the realities of his human nature. The fact that the repressed purposes, nevertheless, remain his is shown by dreams and neurotic symptoms, which represent an irruption of the unconscious into consciousness, producing not indeed a pure image of the unconscious but a compromise between the two conflicting systems, and thus exhibiting the reality of the conflict.

Thus the notion of the unconscious remains an enigma without the theory of repression; or, as Freud says, “We obtain our theory of the unconscious from the theory of repression.” To put it another way, the unconscious is “the dynamically unconscious repressed.” [This] psychic conflict … Freud illustrates [with the term] “civil war.”

what every new person to spiritual practice must understand

For dreams, also “normal” phenomena, exhibit in detail not only the existence of the unconscious but also the dynamics of its repression (the dream-censorship). But since the same dynamics of repression explained neurotic symptoms, and since the dreams of neurotics, which are a clue to the meaning of their symptoms, differ neither in structure nor in content from the dreams of normal people, the conclusion is that a dream is itself a neurotic symptom. We are all therefore neurotic. At least dreams show that the difference between neurosis and health prevails only by day; and since the psychopathology of everyday life exhibits the same dynamics, even the waking life of the “healthy” man is pervaded by innumerable symptom-formations. Between “normality” and “abnormality” there is no qualitative but only a quantitative difference, based largely on the practical question of whether our neurosis is serious enough to incapacitate us for work. … [or, is it that] the “healthy” have a socially usual form of neurosis. … Neurosis is not an occasional aberration; it is not just in other people; it is in us, and in us all the time. The psychic conflict which produces dreams and neuroses is not generated by intellectual problems but by purposes, wishes, desires. … Now if we take “desire” as [an] abstract of this series of terms, it is a Freudian axiom that the essence of man consists not, as Descartes maintained, in thinking, but in desiring. Plato … identified the summum bonum for man with contemplation [but then also in his] doctrine of Eros … suggests that the fundamental quest for man is to find a satisfactory object for his love. … Freudian psychology eliminates the category of pure contemplation as non-existent. Only a wish, says Freud, can possibly set our psychic apparatus in motion. Dreams and neurotic symptoms show that the frustrations of reality cannot destroy the desires which are the essence of our being: the unconscious is the unsubdued and indestructible element in the human soul. The whole world may be against [a person’s secret wishes], but still a man holds fast to the deep-rooted, passionate striving for a positive fulfillment of happiness. The conscious self, on the other hand, which by refusing to admit a desire into consciousness institutes the process of repression, is, so to speak, the surface of ourselves mediating between our inner real being and external reality. … The conscious self is the organ of adaptation to the environment and to culture. The conscious self, therefore, is governed not by [the secret wishes of the hidden man] but by the principle of adjustment to [surface] reality, the reality-principle. … dreams, neurotic symptoms, and all other manifestations of the unconscious, such as fantasy, represent in some degree or other a flight or alienation from a [surface[ reality which is found unbearable. On the other hand, they represent a return to the [deeper reality]; they are substitutes for pleasures denied by [surface] reality. … man … creates culture and society in order to repress himself.

Ernest Becker: The Denial of Death The irony of man's condition is that the deepest need is to be free of the anxiety of death and annihilation; but it is life itself which awakens it, and so we must shrink from being fully alive. … as the Eastern sages also knew, man is a worm and food for worms. This is the paradox: he is out of nature and hopelessly in it; he is dual, up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill-marks to prove it. His body is a material fleshy casing that is alien to him in many ways—the strangest and most repugnant way being that it aches and bleeds and will decay and die. Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever. It is a terrifying dilemma to be in and to have to live with. The lower animals are, of course, spared this painful contradiction, as they lack a symbolic identity and the self-consciousness that goes with it. They merely act and move reflexively as they are driven by their instincts. If they pause at all, it is only a physical pause; inside they are anonymous, and even their faces have no name. They live in a world without time, pulsating, as it were, in a state of dumb being. This is what has made it so simple to shoot down whole herds of buffalo or elephants. The animals don't know that death is happening and continue grazing placidly while others drop alongside them. The knowledge of death is reflective and conceptual, and animals are spared it. They live and they disappear with the same thoughtlessness: a few minutes of fear, a few seconds of anguish, and it is over. But to live a whole lifetime with the fate of death haunting one's dreams and even the most sun-filled days—that's something else. The great boon of repression is that it makes it possible to live decisively in an overwhelmingly miraculous and incomprehensible world, a world so full of beauty, majesty, and terror that if animals perceived it all they would be paralyzed to act. ... What would the average man do with a full consciousness of absurdity? He has fashioned his character for the precise purpose of putting it between himself and the facts of life; it is his special tour-de-force that allows him to ignore incongruities, to nourish himself on impossibilities, to thrive on blindness. He accomplishes thereby a peculiarly human victory: the ability to be smug about terror.

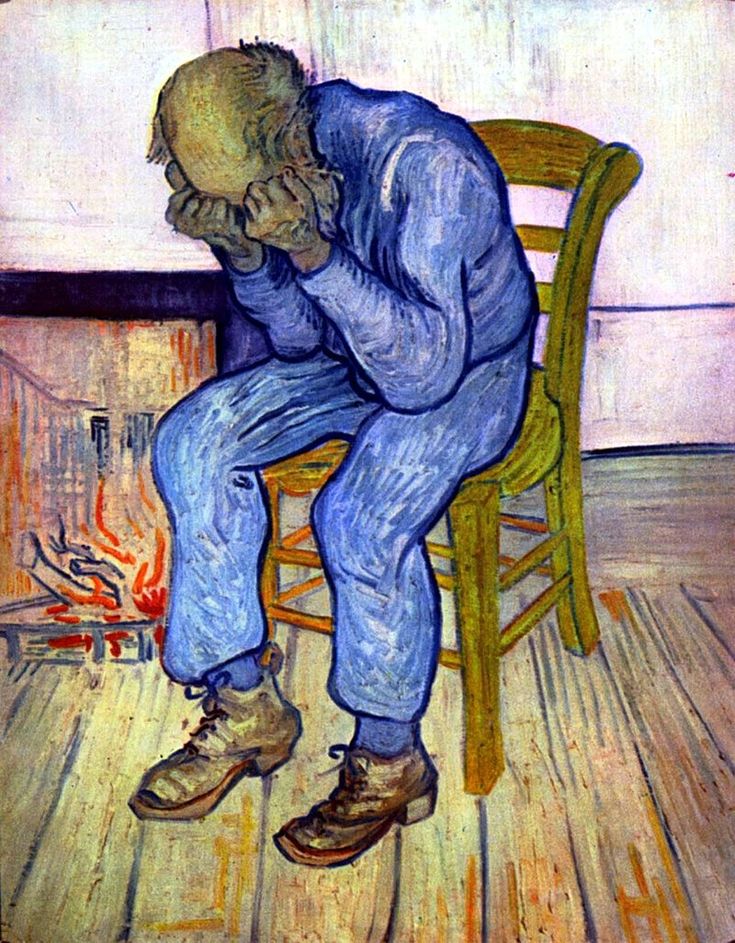

Vincent van Gogh, "Old Man in Sorrow" (On the Threshold of Eternity), 1890

Man cuts out for himself a manageable world: he throws himself into action uncritically, unthinkingly. He accepts the cultural programming that turns his nose where he is supposed to look; he doesn’t bite the world off in one piece as a giant would, but in small manageable pieces, as a beaver does. He uses all kinds of techniques, which we call the “character defenses”: he learns not to expose himself, not to stand out; he learns to embed himself in other-power, both of concrete persons and of things and cultural commands; the result is that he comes to exist in the imagined infallibility of the world around him. He doesn’t have to have fears when his feet are solidly mired and his life mapped out in a ready-made maze. All he has to do is to plunge ahead in a compulsive style of drivenness in the “ways of the world.” To grow up at all is to conceal the mass of internal scar tissue that throbs in our dreams. He has no doubts, there is nothing you can say to sway him, to give him hope or trust. He is a miserable animal whose body decays, who will die, who will pass into dust and oblivion, disappear forever not only in this world but in all the possible dimensions of the universe, whose life serves no conceivable purpose, who may as well not have been born, and so on and so forth. What does it mean to be a self-conscious animal? The idea is ludicrous, if it is not monstrous. It means to know that one is food for worms. This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression and with all this yet to die. It seems like a hoax, which is why one type of cultural man rebels openly against the idea of God. What kind of deity would create such a complex and fancy worm food? “I drink not from mere joy in wine nor to scoff at faith—no, only to forget myself for a moment, that only do I want of intoxication, that alone. —OMAR KHAYYAM” Kierkegaard gives us some portrait sketches of the styles of denying possibility, or the lies of character-which is the same thing. He is intent on describing what we today call "inauthentic" men, men who avoid developing their own uniqueness; they follow out the styles of automatic and uncritical living in which they were conditioned as children. They are "inauthentic" in that they do not belong to themselves, are not "their own" person, do not act from their own center, do not see reality on its terms; they are the one-dimensional men totally immersed in the fictional games being played in their society, unable to transcend their social conditioning: the corporation men in the West, the bureaucrats in the East, the tribal men locked up in tradition-man everywhere who doesn't understand what it means to think for himself and who, if he did, would shrink back at the idea of such audacity and exposure. We don't want to admit that we do not stand alone, that we always rely on something that transcends us, some system of ideas and powers in which we are embedded and which support us. This power is not always obvious. It need not be overtly a god or openly a stronger person, but it can be the power of an all-absorbing activity, a passion, a dedication to a game, a way of life, that like a comfortable web keeps a person buoyed up and ignorant of himself, of the fact that he does not rest on his own center. All of us are driven to be supported in a self-forgetful way, ignorant of what energies we really draw on, of the kind of lie we have fashioned in order to live securely and serenely. Augustine was a master analyst of this, as were Kierkegaard, Scheler, and Tillich in our day. They saw that man could strut and boast all he wanted, but that he really drew his "courage to be" from a god, a string of sexual conquests, a Big Brother, a flag, the proletariat, and the fetish of money and the size of a bank balance. We can conclude that a project as grand as the scientific-mythical construction of victory over human limitation is not something that can be programmed by science. Even more, it comes from the vital energies of masses of men sweating within the nightmare of creation-and it is not even in man's hands to program. Who knows what form the forward momentum of life will take in the time ahead or what use it will make of our anguished searching. The most that any one of us can seem to do is to fashion something-an object or ourselves-and drop it into the confusion, make an offering of it, so to speak, to the life force. Early theorists of group psychology had tried to explain why men were so sheeplike when they functioned in groups. They developed ideal like "mental contagion" and "herd instinct," which became very popular. But as Freud was quick to see, these ideas never really did explain what men did with their judgment and common sense when they got caught up in groups. Freud saw right away what they did with it: they simply became dependent children again, blindly following the inner voice of their parents, which now came to them under the hypnotic spell of the leader. They abandoned their egos to his, identified with his power, tried to function with him as an ideal. Why does man accept to live a trivial life? Because of the danger of a full horizon of experience, of course. This is the deeper motivation of philistinism, that it celebrates the triumph over possibility, over freedom. Philistinism knows its real enemy: freedom is dangerous. If you follow it too willingly it threatens to pull you into the air; if you give it up too wholly, you become a prisoner of necessity. The safest thing is to toe the mark of what is socially possible. It is clear to us today, too, that Freud was wrong about the dogma, just as Jung and Adler knew right at the beginning. Man has no innate instincts of sexuality and aggression. Now we are seeing something more, the new Freud emerging in our time, that he was right in his dogged dedication to revealing man's creatureliness. His emotional involvement was correct. It reflected the true intuitions of genius, even though the particular intellectual counterpart of that emotion-the sexual theory-proved to be wrong. Man's body was "a curse of fate," and culture was built upon repression - not because man was a seeker only of sexuality, of pleasure, of life and expansiveness, as Freud thought, but because man was also primarily an avoider of death. Consciousness of death is the primary repression, not sexuality. As Rank unfolded in book after book, and as Brown has recently again argued, the new perspective on psychoanalysis is that its crucial concept is the repression of death. This is what is creaturely about man, this is the repression on which culture is built, a repression unique to the self-conscious animal. Freud saw the curse and dedicated his life to revealing it with all the power at his command. But he ironically missed the precise scientific reason for the curse. We cannot repeat too often the great lesson of freudian psychology: that repression is normal self-protection and creative self-restriction--in a real sense, man's natural substitute for instinct. Rank has a perfect, key term for this natural human talent: he calls it "partialization" and very rightly sees that life is impossible without it. What we call the well-adjusted man has just this capacity to partialize the world for comfortable action. I have used the term "fetishization," which is exactly the same idea: the "normal" man bites off what he can chew and digest of life, and no more. In other words, men aren't built to be gods, to take in the whole world; they are built like other creatures, to take in the piece of ground in front of their noses. Gods can take in the whole of creation because they alone can make sense of it, know what it is all about and for. But as soon as a man lifts his nose from the ground and starts sniffing at eternal problems like life and death, the meaning of a rose or a star cluster - then he is in trouble. Most men spare themselves this trouble by keeping their minds on the small problems of their lives just as their society maps these problems out for them. These are what Kierkegaard called the "immediate" men and the "Philistines." They "tranquilize themselves with the trivial"- and so they can lead normal lives. The most terrifying burden of the creature is to be isolated, which is what happens in individuation: one separates himself out of the herd. This move exposes the person to the sense of being completely crushed and annihilated because he sticks out so much, has to carry so much in himself. These are the risks when the person begins to fashion consciously and critically his own framework of heroic self-reference. Here is precisely the definition of the artist type, or the creative type generally. We have crossed a threshold into a new type of response to man’s situation. No one has written about this type of human response more penetratingly than Rank; and of all his books, Art and Artist is the most secure monument to his genius. Kierkegaard had his own formula for what it means to be a man. He put it forth in those superb pages wherein he describes what he calls "the knight of faith." This figure is the man who lives in faith, who has given over the meaning of life to his Creator, and who lives centered on the energies of his Maker. He accepts whatever happens in this visible dimension without complaint, lives his life as a duty, faces his death without a qualm. No pettiness is so petty that it threatens his meanings; no task is too frightening to be beyond his courage. He is fully in the world on its terms and wholly beyond the world in his trust in the invisible dimension. It is very much the old Pietistic ideal that was lived by Kant's parents. The great strength of such an ideal is that it allows one to be open, generous, courageous, to touch others' lives and enrich them and open them in turn. As the knight of faith has no fear-of-life-and-death trip to lay onto others, he does not cause them to shrink back upon themselves, he does not coerce or manipulate them. The knight of faith, then, represents what we might call an ideal of mental health, the continuing openness of life out of the death throes of dread. The "healthy" person, the true individual, the self-realized soul, the "real" man, is the one who has transcended himself. A person spends years coming into his own, developing his talent, his unique gifts, perfecting his discriminations about the world, broadening and sharpening his appetite, learning to bear the disappointments of life, becoming mature, seasoned-finally a unique creature in nature, standing with some dignity and nobility and transcending the animal condition; no longer driven, no longer a complex reflex, not stamped out of any mold. And then the real tragedy, as Andre Malraux wrote in The Human Condition: that it takes sixty years of incredible suffering and effort to make such an individual, and then he is good only for dying. This painful paradox is not lost on the person himself--least of all himself. He feels agonizingly unique, and yet he knows that this doesn't make any difference as far as ultimates are concerned. Best of all, of course, religion solves the problem of death, which no living individuals can solve, no matter how they would support us. Religion, then, gives the possibility of heroic victory in freedom and solves the problem of human dignity at it highest level. The two ontological motives of the human condition are both met: the need to surrender oneself in full to the the rest of nature, to become a part of it by laying down one's whole existence to some higher meaning; and the need to expand oneself as an individual heroic personality. Finally, religion alone gives hope, because it holds open the dimension of the unknown and the unknowable, the fantastic mystery of creation that the human mind cannot even begin to approach, the possibility of a multidimensionality of spheres of existence, of heavens and possible embodiments that make a mockery of earthly logic-and in doing so, it relieves the absurdity of earthly life, all the impossible limitations and frustrations of living matter. In religious terms, to "see God" is to die, because the creature is too small and finite to be able to bear the higher meanings of creation. Religion takes one's very creatureliness, one's insignificance, and makes it a condition of hope. Full transcendence of the human condition means limitless possibility unimaginable to us. He can even give his body over to the tribe, the state, the embracing magical umbrella of the elders and their symbols; that way it will no longer be a dangerous negation for him. But there is no real difference between a childish impossibility and an adult one; the only thing that the person achieves is a practiced self-deceit—what we call the “mature” character. In Christendom he too is a Christian, goes to church every Sunday, hears and understands the parson, yea, they understand one another; he dies; the parson introduces him into eternity for the price of $10—but a self he was not, and a self he did not become…. It is not so much that man is a herd animal, said Freud, but that he is a horde animal led by a chief. It is this alone that can explain the "uncanny and coercive characteristics of group formations." The chief is a "dangerous personality, toward whom only a passive-masochistic attitude is possible, to whom one's will has to be surrendered,-while to be alone with him, 'to look him in the face,' appears a hazardous enterprise." This alone, says Freud, explains the "paralysis" that exists in the link between a person with inferior power to one of superior power. Man has "an extreme passion for authority" and "wishes to be governed by unrestricted force." It is this trait that the leader hypnotically embodies in his own masterful person. Or as Fenichel later put it, people have a "longing for being hypnotized" precisely because they want to get back to the magical protection, the participation in omnipotence, the "oceanic feeling" that they enjoyed when they were loved and protected by their parents. And so, as Freud argues, it is not that groups bring out anything new in people; it is just that they satisfy the deep-seated erotic longings that people constantly carry around unconsciously. For Freud, this was the life force that held groups together. It functioned as a kind of psychic cement that locked people into mutual and mindless interdependence: the magnetic powers of the leader, reciprocated by the guilty delegation of everyone's will to him. We might call this existential paradox the condition of individuality finitude. Man has a symbolic identity that brings him sharply out of nature. He is a symbolic self, a creature with a name, a life history. He is a creator with a mind that soars out to speculate about atoms and infinity, who can place himself imaginatively at a point in space and contemplate bemusedly his own planet. This immense expansion, this dexterity, this ethereality, this self-consciousness gives to man literally the status of a small god in nature, as the Renaissance thinkers knew. Yet, at the same time, as the Eastern sages also knew, man is a worm and food for worms. Generally speaking, we call neurotic any life style that begins to constrict too much, that prevents free forward momentum, new choices, and growth that a person may want and need. For example, a person who is trying to find his salvation only in a love relationship but who is being defeated by this too narrow focus is neurotic. He can become overly passive and dependent, fearful of venturing out on his own, of making his life without his partner, no matter how that partner treats him. The object has become his “All,” his whole world; and he is reduced to the status of a simple reflex of another human being. We called one's lifestyle a vital lie, and now we can understand better why we said it was vital: it is a necessary and basic dishonesty about oneself and one's whole situation... We don't want to admit that we are fundamentally dishonest about reality, that we do not really control our own lives. In other words, the fear of death must be present behind all our normal functioning, in order for the organism to be armed toward self-preservation. But the fear of death cannot be present constantly in one's mental functioning, else the organism could not function. Zilboorg continues: If this fear were as constantly conscious, we should be unable to function normally. It must be properly repressed to keep us living with any modicum of comfort. We know very well that to repress means more than to put away and to forget that which was put away and the place where we put it. It means also to maintain a constant psychological effort to keep the lid on and inwardly never relax our watchfulness. And so we can understand what seems like an impossible paradox: the ever-present fear of death in the normal biological functioning of our instinct of self-preservation, as well as our utter obliviousness to this fear in our conscious life: Therefore in normal times we move about actually without ever believing in or own death, as if we fully believed in our own corporeal immortality. We are intent on mastering death... A man will say, of course, that he knows he will die some day, but he does not really care. He is having a good time with living, and he does not think about death and does not care to bother about it-but this is a purely intellectual, verbal admission. The affect of fear is repressed. Sartre has called man a "useless passion" because he is so hopelessly bungled, so deluded about his true condition. He wants to be a god with only the equipment of an animal, and so he thrives on fantasies. As Ortega so well put it..., man uses his ideas for the defense of his existence, to frighten away reality. This is a serious game, the defense of one's existence-how take it away from people and leave them joyous? How does one transcend himself; how does he open himself to new possibility? By realizing the truth of his situation, by dispelling the lie of his character, by breaking his spirit out of its conditioned prison. … The child has built up strategies and techniques for keeping his self-esteem in the face of the terror of his situation. These techniques become an armor that hold the person prisoner. The very defenses that he needs in order to move about with self-confidence and self-esteem become his life-long trap. In order to transcend himself he must break down that which he needs in order to live. … In the prison of one's character one can pretend and feel that he is somebody, that the world is manageable, that there is a reason for one's life, a ready justification for one's action. To live automatically and uncritically is to be assured of at least a minimum share of the programmed cultural heroics-what we might call "prison heroism": the smugness of the insiders who "know.” Is one oppressed by the burden of his life? Then he can lay it at his divine partner's feet. Is self-consciousness too painful, the sense of being a separate individual, trying to make some kind of meaning out of who one is, what life is, and the like? Then one can wipe it away in the emotional yielding to the partner, forget oneself in the delirium of sex, and still be marvelously quickened in the experience. Is one weighed down by the guilt of his body, the drag of his animality that haunts his victory over decay and death? But this is just what the comfortable sex relationship is for: in sex, the body and the consciousness of it are no longer separated; the body is no longer something we look at as alien to ourselves. As soon as it is fully accepted as a body by the partner, our self-consciousness vanishes; it merges with the body and with the self-consciousness and body of the partner. Four fragments of existence melt into one unity and things are no longer disjointed and grotesque: everything is "natural," functional, expressed as it should be-and so it is stilled and justified. All the more is guilt wiped away when the body finds its natural usage in the production of a child. And this brings us to our final type of man: the one who asserts himself out of defiance of his own weakness, who tries to be a god unto himself, the master of his fate, a self-created man. He will not be merely the pawn of others, of society; he will not be a passive sufferer and secret dreamer, nursing his own inner flame in oblivion. He will plunge into life, into the distractions of great undertakings, he will become a restless spirit...which wants to forget...Or he will seek forgetfulness in sensuality, perhaps in debauchery.... At its extreme, defiant self-creation can become demonic, a passion which Kierkegaard calls "demoniac rage," an attack on all of life for what it has dared to do to one, a revolt against existence itself.” The ironic thing about the narrowing-down of neurosis is that the person seeks to avoid death, but he does it by killing off so much of himself and so large a spectrum of his action-world that he is actually isolating and diminishing himself and becomes as though dead. There is just no way for the living creature to avoid life and death, and it is probably poetic justice that if he tries too hard to do so he destroys himself. Maslow used an apt term for this evasion of growth, this fear of realizing one's own fullest powers. He called it the "Jonah Syndrome." He understood the syndrome as the evasion of the full intensity of life: We are just not strong enough to endure more! It is just too shaking and wearing. So often people in...ecstatic moments say, "It's too much," or "I can't stand it," or "I could die"....Delirious happiness cannot be borne for long. Our organisms are just too weak for any large doses of greatness.... The Jonah Syndrome, then, seen from this basic point of view, is "partly a justified fear of being torn apart, of losing control, of being shattered and disintegrated, eve of being killed by the experience." And the result of this syndrome is what we would expect a weak organism to do: to cut back the full intensity of life: For some people this evasion of one's own growth, setting low levels of aspiration, the fear of doing what one is capable of doing, voluntary self-crippling, pseudo-stupidity, mock-humility are in fact defenses against grandiosity... It all boils down to a simple lack of strength to bear the superlative, to open oneself to the totality of experience-an idea that was well appreciated by William James and more recently was developed in phenomenological terms in the classic work of Rudolf Otto. Otto talked about the terror of the world, the feeling of overwhelming awe, wonder, and fear in the face of creation-the miracle of it, the mysterium tremendum et fascinosum of each single thing, of the fact that there are things at all. What Otto did was to get descriptively at man's natural feeling of inferiority in the face of the massive transcendence of creation; his real creature feeling before the crushing negating miracle of Being. For Kierkegaard “philistinism” was triviality, man lulled by the daily routines of his society, content with the satisfactions that it offers him: in today’s world the car, the shopping center, the two-week summer vacation. Man is protected by the secure and limited alternatives his society offers him, and if he does not look up from his path he can live out his life with a certain dull security: Devoid of imagination, as the Philistine always is, he lives in a certain trivial province of experience as to how things go, what is possible, what usually occurs… . Philistinism tranquilizes itself in the trivial… But nature has protected the lower animal by endowing them with instincts. An instinct is a programmed perception that calls into play a programmed reaction. It is very simple. Animals are not moved by what they cannot react to. They live in a tiny world, a sliver of reality, one neuro-chemical program that keeps them walking behind their nose and shuts out everything else. But look at man, the impossible creature! Here nature seems to have thrown caution to the winds along with the programmed instincts. She created an animal who has no defense against full perception of the external world, an animal completely open to experience. Not only in front of his nose, in his umwelt, but in many umwelten. He can relate not only to animals in his own species, but in some ways to all other species. He can contemplate not only what is edible for him, but everything that grows. He not only lives in this moment, but expands his inner self to yesterday, his curiosity to centuries ago, his fears to five billion years from now when the sun will cool, his hopes to an eternity from now. He lives not only on a tiny territory, nor even on an entire planet, but in a galaxy, in a universe, and in dimensions beyond visible universes. It is appalling, the burden that man bears, the experiential burden. As we saw in the last chapter, man can't even take his own body for granted as can other animals. It is not just hind feet, a tail that he drags, that are just "there," limbs to be used and taken for granted or chewed off when caught in a trap and when they give pain and prevent movement. Man's body is a problem to him that has to be explained. Not only his body is strange, but also its inner landscape, the memories and dreams. Man's very insides-his self-are foreign to him. He doesn't know who he is, why he was born, what he is doing on the planet, what he is supposed to do, what he can expect. His own existence is incomprehensible to him, a miracle just like the rest of creation, closer to him, right near his pounding heart, but for that reason all the more strange. Each thing is a problem, and man can shut out nothing. As Maslow has well said, "It is precisely the godlike in ourselves that we are ambivalent about, fascinated by and fearful of, motivated to and defensive against. This is one aspect of the basic human predicament, that we are simultaneously worms and gods." There it is again: gods with anuses. Sex is of the body, and the body is of death. This is how we understand depressive psychosis today: as a bogging down in the demands of others--family, job, the narrow horizon of daily duties. In such a bogging down the individual does not feel or see that he has alternatives, cannot imagine any choices or alternate ways of life, cannot release himself from the network of obligations even though these obligations no longer give him a sense of self-esteem, of primary value, of being a heroic contributor to world life even by doing his daily family and job duties. As I once speculated, the schizophrenic is not enough built into his world--what Kierkegaard has called the sickness of infinitude; the depressive, on the other hand, is built into his world too solidly, too overwhelmingly. Kierkegaard put it this way: But while one sort of despair plunges wildly into the infinite and loses itself, a second sort permits itself as it were to be defrauded by "the others." By seeing the multitude of men about it, by getting engaged in all sorts of worldly affairs, by becoming wise about how things go in this world, such a man forgets himself...does not dare to believe in himself, finds it too venturesome a thing to be himself, far easier and safer to be like the others, to become an imitation, a number, a cipher in the crowd. This is a superb characterization of the "culturally normal" man, the one who dares not stand up for his own meanings because this means too much danger, too much exposure. Better not to be oneself, better to live tucked into others, embedded in a safe framework of social and cultural obligations and duties. Again, too, this kind of characterization must be understood as being on a continuum, at the extreme end of which we find depressive psychosis. The depressed person is so afraid of being himself, so fearful of exerting his own individuality, of insisting on what might be his own meanings, his own conditions for living, that he seems literally stupid. He cannot seem to understand the situation he is in, cannot see beyond his own fears, cannot grasp why he has bogged down. Kierkegaard phrases it beautifully: If one will compare the tendency to run wild in possibility with the efforts of a child to enunciate words, the lack of possibility is like being dumb...for without possibility a man cannot, as it were, draw breath. This is precisely the condition of depression, that one can hardly breathe or move. One of the unconscious tactics that the depressed person resorts to, to try to make sense out of his situation, is to see himself as immensely worthless and guilty. This is a marvelous "invention" really, because it allows him to move out of his condition of dumbness, and make some kind of conceptualization of his situation, some kind of sense out of it-even if he has to take full blame as the culprit who is causing so much needless misery to others. Could Kierkegaard have been referring to just such an imaginative tactic when he casually observed: Sometimes the inventiveness of the human imagination suffices to procure possibility.... The person is both a self and a body, and from the beginning there is the confusion about where "he" really "is"-in the symbolic inner self or in the physical body. Each phenomenological realm is different. The inner self represents the freedom of thought, imagination, and the infinite reach of symbolism. the body represents determinism and boundness. The child gradually learns that his freedom as a unique being is dragged back by the body and its appendages which dictate "what" he is. For this reason sexuality is as much a problem for the adult as for the child: the physical solution to the problem of who we are and why we have emerged on this planet is no help-in fact, it is a terrible threat. It doesn't tell the person what he is deep down inside, what kind of distinctive gift he is to work upon the world. This is why it is so difficult to have sex without guilt: guilt is there because the body casts a shadow on the person's inner freedom, his "real self" that-through the act of sex-is being forced into a standardized, mechanical, biological role. Even worse, the inner self is not even being called into consideration at all; the body takes over completely for the total person, and this kind of guilt makes the inner self shrink and threaten to disappear. This is why a woman asks for assurance that the man wants "me" and "not only my body"; she is painfully conscious that her own distinctive inner personality can be dispensed with in the sexual act. If it is dispensed with, it doesn't count. The fact is that the man usually does want only the body, and the woman's total personality is reduced to a mere animal role. The existential paradox vanishes, and one has no distinctive humanity to protest. One creative way of coping with this is, of course, to allow it to happen and to go with it: what the psychoanalysts call "regression in the service of the ego." The person becomes, for a time, merely his physical self and so absolves the painfulness of the existential paradox and the guilt that goes with sex. Love is one great key to this kind of sexuality because it allows the collapse of the individual into the animal dimension without fear and guilt, but instead with trust and assurance that his distinctive inner freedom will not be negated by an animal surrender. Freud's greatest discovery, the one which lies at the root of psychodynamics, is that the great cause of much psychological illness is the fear of knowledge of oneself- one's emotions, impulses, memories, capacities, potentialities, of one’s destiny. We have discovered that fear of knowledge of oneself is very often isomorphic with, and parallel with, fear of the outside world. And what is this fear, but a fear of the reality of creation in relation to our powers and possibilities: In general this kind of fear is defensive, in the sense that it is a protection of our self-esteem, of our love and respect for ourselves. We tend to be afraid of any knowledge that could cause us to despise ourselves or to make us feel inferior, weak, worthless, evil, shameful. We protect ourselves and our ideal image of ourselves by repression and similar defenses, which are essentially techniques by which we avoid becoming conscious of unpleasant or dangerous truths.

Eric Hoffer: The True Believer The permanent misfits can find salvation only in a complete separation from the self; and they usually find it by losing themselves in the compact collectivity of a mass movement. Faith in a holy cause is to a considerable extent a substitute for the lost faith in ourselves. Glory is largely a theatrical concept. There is no striving for glory without a vivid awareness of an audience... The desire to escape or camouflage their unsatisfactory selves develops in the frustrated a facility for pretending -- for making a show -- and also a readiness to identify themselves wholly with an imposing spectacle. If a doctrine is not unintelligible, it has to be vague; and if neither unintelligible nor vague, it has to be unverifiable. The opposite of the religious fanatic is not the fanatical atheist but the gentle cynic who cares not whether there is a God or not. The atheist is a religious person. He believes in atheism as though it were a new religion. Every extreme attitude is a flight from the self. An effective mass movement cultivates the idea of sin. It depicts the autonomous self not only as barren and helpless but also as vile. To confess and repent is to slough off one’s individual distinctness and separateness, and salvation is found by losing oneself in the holy oneness of the congregation. Those who would transform a nation or the world cannot do so by breeding and captaining discontent or by demonstrating the reasonableness and desirability of the intended changes or by coercing people into a new way of life. They must know how to kindle and fan an extravagant hope. The loyalty of the true believer is to the whole -- the church, party, nation -- and not to his fellow true believer. The less justified a man is in claiming excellence for his own self, the more ready he is to claim all excellence for his nation, his religion, his race or his holy cause. A mass movement attracts and holds a following not because it can satisfy the desire for self-advancement, but because it can satisfy the passion for self-renunciation. They who clamor loudest for freedom are often the ones least likely to be happy in a free society. The frustrated, oppressed by their shortcomings, blame their failure on existing restraints. Actually their innermost desire is for an end to the “free for all.” They want to eliminate free competition and the ruthless testing to which the individual is continually subjected in a free society. Those who see their lives as spoiled and wasted crave equality and fraternity more than they do freedom. If they clamor for freedom, it is but freedom to establish equality and uniformity. The passion for equality is partly a passion for anonymity: to be one thread of the many which make up a tunic; one thread not distinguishable from the others. No one can then point us out, measure us against others and expose our inferiority. There is also this: when we renounce the self and become part of a compact whole, we not only renounce personal advantage but are also rid of personal responsibility. There is no telling to what extremes of cruelty and ruthlessness a man will go when he is freed from the fears, hesitations, doubts and vague stirrings of decency that go with individual judgment.

|

|||||

|

|