|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Emily Dickinson If you were coming in the fall (#511)

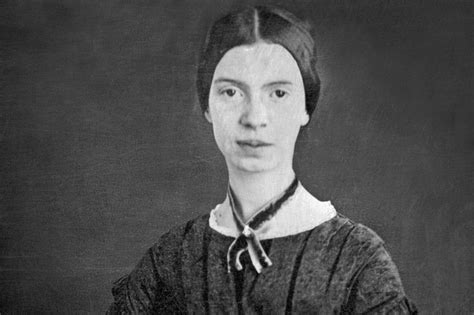

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

If you were coming in the fall, If I could see you in a year, If only centuries delayed, If certain, when this life was out, But now, all ignorant of the length

Theme The main theme of this poem is uncertainty—specifically, how it applies to love and one’s willingness to wait for true love. The speaker initially feels as though she’d wait through any season, year, or century, for her lover. But, as she expands this imaginary scenario into reality, she realizes it’s far harder to do so than she expected. Poem Meaning Throughout this piece, the poet asserts that love is different, in reality, than it is in one’s imagination. She becomes uncertain as the stanzas continue whether or not she could truly follow through on her assertions that she’d wait century after century for her lover.

If you were coming in the Fall, I’d brush the Summer by With half a smile, and half a spurn, As Housewives do, a Fly. In the first stanza of the poem, the poet begins by crafting a series of images that allude to her connection to “you.” The person to whom the speaker is directing their words is commonly considered to be a lover. But, it’s unclear whether or not Dickinson had a specific person in mind when she wrote this poem or was channeling a persona. The speaker tells her lover that if they were “coming in the Fall,” then she’d happily lose the summer. She’d push it to the side, shooing it off as one might do a “Fly.” She compares her willingness to lose time, specifically summer months (which are commonly associated with positive feelings and optimism in poetry), in order to be with her lover sooner. Often, the seasons are used as symbols of the periods of one’s life. So, the speaker’s willingness to lose “summer,” which is generally used to symbolize the peak of one’s existence, and move into fall, is highly meaningful. Stanza Two If I could see you in a year, I’d wind the months in balls— And put them each in separate Drawers, For fear the numbers fuse— In the next stanza, the poet’s speaker brings in more images that help convey her love for “you.” She’d be willing to wait an entire “year” to see her lover, and it would be nothing to her. She’d wind up the months into balls and “put them each in separate Drawers.” She’d set them to the side easily, happy to move through her life quickly and reach the moment she’s reunited with her lover. The speaker expresses a fear she has regarding the passage of time in the final lines. By putting the woolen balls, symbolizing the months she’s waiting for her lover, into separate drawers, she’s keeping them from fusing. She’s categorizing them so that she never becomes overwhelmed by the days, weeks, and months she’s been forced to contend with. Stanza Three If only Centuries, delayed, I’d count them on my Hand, Subtracting, til my fingers dropped Into Van Dieman’s Land, As the stanzas progress, the poet increases the period of time that her speaker is considering waiting for her lover. From the first stanza, beginning with a season, she’s moved on to discussing the possibility of centuries. She’s planning to wait as long as she needs to, counting the centuries on her fingers until she sees her lover again and puts them down. But, there’s also the possibility, she admits, that she’ll wait so long that her fingers will “drop…Into Van Dieman’s Land.” Here, the poet is alluding to Tasmania, an island of Australia known initially as “Van Dieman’s Land” when it was colonized in 1825. By making this very specific allusion, she’s suggesting that her desolation in combination with the amount of time she’s willing to wait will result in her wasting away, eventually seeing her own fingers fall to the other side of the world to a place that, very likely, was completely unknown to the poet. The area was best-known as a place where convicts were sent from England. In the same way that these people disappear, so too will her fingers when she wastes away from counting centuries. Stanza Four If certain, when this life was out— That yours and mine, should be I’d toss it yonder, like a Rind, And take Eternity— In the fourth stanza of this memorable poem, the speaker says that if she knew for sure that, after her life was over, she’d be with “you,” then she’d throw her life away (just as she was willing to shoo away summer in the first stanza). She’d “toss” her life “yonder, like a Rind.” Here, she’s comparing her life to a rind or the outer layer of a piece of fruit (like an orange). Her life would be as meaningless as a discarded piece of trash if, in death, she could be with her lover. She would take eternity with them over living another day of her present life. Stanza Five But, now, uncertain of the length Of this, that is between, It goads me, like the Goblin Bee— That will not state— its sting. In the final stanza of ‘If you were coming in the Fall,’ the poet’s speaker says that she has no idea if she’s ever going to see this person again. She doesn’t know if they’ll return in the fall, in a year, or in a century. This makes her feel incredibly uncertain and unsure of what she should do. The “Goblin Bee,” a simile for the intense situation she’s in, is always there with its sting. It represents reality and how, in an imaginary sense, it’s nice to consider how long she’d wait for her lover. But, in the real world, it’s far more difficult. What is the purpose of ‘If you were coming in the Fall?’ The purpose is to explore the strength of love and how it differs in one’s imagination and in the real world. The speaker feels that she’d nearly waited forever for her lover. But, when she really considers it, the thought of waiting endlessly for love is far harder to endure. The tone varies from optimistic and determined to uncertain and emotional in the final lines. The speaker becomes restless regarding her ability to wait forever for her longer when she really starts to consider what that would entail.

1775 poems

|

||

|

|