|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||||||

|

Word Gems self-knowledge, authentic living, full humanity, continual awakening

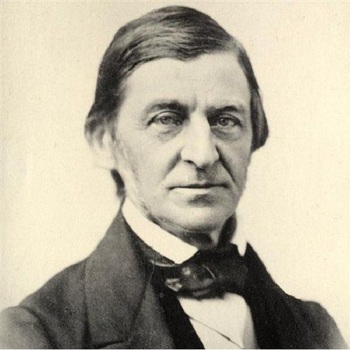

Emerson Experience

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

ChatGPT offers commentary: Here is the complete public-domain text of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Experience” (first published 1844 in Essays: Second Series), including the original epigraph, in numbered paragraphs. Experience (1844) — Ralph Waldo EmersonEpigraph: Paraphrase: These forces include usefulness and surprise, what we can see on the surface and what exists only in dreams, the steady flow of time, and even wrongdoing that feels ghostly and impersonal. There is also human temperament — our built-in dispositions — operating silently, without explanation, and behind it all, the unnamed presence that devised the very rules of life and is everywhere at once. Some of these forces can be clearly recognized, while others must be inferred or sensed indirectly. As they move steadily across the world, a small human figure — humanity itself — wanders among them, confused and dwarfed by their scale. This human does not yet understand what he is seeing or how he belongs. Nature, portrayed as a loving guardian, gently takes the human by the hand. She reassures him not to worry: these forces are not fixed or final. They will change their appearance with time. And more than that — the human himself is not merely subject to them. He is their originator and future shaper. These vast forces are, in some profound sense, his own creation and inheritance. Glossary Modern connection It’s easy to feel small and confused inside these systems. But Emerson offers a quietly radical reassurance: humans are not merely trapped inside these forces — we participate in creating them. Our ideas, values, and choices eventually reshape what once seemed fixed. What overwhelms us now may later wear a different face, shaped by the very people who once felt powerless beneath it. Paragraph 1. Where do we find ourselves? In a series of which we do not know the extremes, and believe that it has none. We wake and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us, which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight. But the Genius which, according to the old belief, stands at the door by which we enter, and gives us the lethe to drink, that we may tell no tales, mixed the cup too strongly, and we cannot shake off the lethargy now at noonday. Paragraph 2. Sleep lingers all our lifetime about our eyes, as night hovers all day in the boughs of the fir-tree. All things swim and glitter. Our life is not so much threatened as our perception. Ghostlike we glide through nature, and should not know our place again. Paraphrase:

According to ancient belief, a guiding spirit stands at the threshold of life and gives each soul a drink of forgetfulness, so that we enter the world without remembering where we came from or what came before. Emerson suggests that this forgetfulness was given in excess. Even in the middle of our lives, when we should be fully awake and alert, we remain drowsy, unable to clearly remember, understand, or explain our own condition. This lingering drowsiness never fully leaves us. We go through life as if half-asleep, seeing the world as hazy, shimmering, and unstable. The danger to our lives is not so much physical harm as it is a failure of perception — a constant inability to see things clearly or firmly. We move through nature like ghosts, detached and uncertain, so estranged from full awareness that we might not even recognize our own place in the world if we encountered it directly. Glossary Modern connection Emerson’s insight feels strikingly modern: the greatest threat isn’t danger itself but distraction, numbness, and partial awareness. We may be physically awake and busy, yet still feel disconnected from meaning, purpose, and our own place in the larger picture — moving through life efficiently, but not fully present. Paragraph 3. Did our birth fall in some fit of indigence and frugality in nature, that she was so sparing of her fire and so liberal of her earth, that it appears to us that we lack the affirmative principle, and though we have health and reason, yet we have no superfluity of spirit for new creation? We have enough to live and bring the year about, but not an ounce to impart or to invest. Paragraph 4. Ah that our Genius were a little more of a genius! We are like millers on the lower levels of a stream, when the factories above them have exhausted the water. We too fancy that the upper people must have raised their dams. Paragraph 5. If any of us knew what we were doing, or where we are going, then when we think we best know! We do not know to-day whether we are busy or idle. In times when we thought ourselves indolent, we have afterwards discovered that much was accomplished, and much was begun in us. All our days are so unprofitable while they pass, that ’tis wonderful where or when we ever got anything of this which we call wisdom, poetry, virtue. We never got it on any dated calendar day. Paraphrase: He wishes that our inner guiding spirit — our “genius” — were more fully alive and powerful. Instead, we resemble millers working downstream after those upstream have already diverted the water. Our efforts feel dry and diminished, as if the essential energy has already been used up elsewhere. We suspect that others before us have somehow blocked the flow, hoarding vitality, opportunity, or inspiration, leaving us with only the leftovers. Yet Emerson immediately complicates this sense of deprivation. He points out how little we actually understand our own lives while we are living them. Even at the moments when we feel most confident, most in control, or most certain about our actions or our path in life, we actually do not know. Our sense of understanding is often illusory. Emerson is emphasizing the gap between our perception of knowledge and the deeper truth of our situation. Even our judgments about whether we are productive or idle are unreliable. Periods we dismiss as lazy or wasted often turn out, in hindsight, to have been deeply formative. Important growth and preparation were quietly taking place beneath the surface. Looking back, it becomes almost mysterious how we ever acquired wisdom, artistic insight, or moral character at all, since none of these things arrived on any clearly marked day or through any visible achievement. Glossary • best know – The moments when we think we understand most clearly, are most competent, or most aware. Modern connection Emerson reframes that anxiety. Growth often happens invisibly, during periods that feel unproductive or stalled. Skills, values, and insight tend to accumulate quietly, not through dramatic breakthroughs but through slow internal changes we only recognize later. What feels like dryness in the moment may actually be a season of unseen preparation. Paragraph 6. Some heavenly days must have been intercalated somewhere, like those that Hermes won with dice of the Moon, that Osiris might be born. It is said all martyrdoms looked mean when they were suffered. Every ship is a romantic object, except that we sail in. Embark, and the romance quits our vessel and hangs on every other sail in the horizon. Our life looks trivial, and we shun to record it. Men seem to have learned of the horizon the art of perpetual retreating and reference. Paragraph 7. “Yonder uplands are rich pasturage, and my neighbor has fertile meadow, but my field,” says the querulous farmer, “only holds the world together.” I quote another man’s saying; unluckily that other withdraws himself in the same way, and quotes me. ’Tis the trick of nature thus to degrade to-day; a good deal of buzz, and somewhere a result slipped magically in. Paragraph 8. Every roof is agreeable to the eye until it is lifted; then we find tragedy and moaning women and hard-eyed husbands and deluges of lethe, and the men ask, “What’s the news?” as if the old were so bad. How many individuals can we count in society? how many actions? how many opinions? So much of our time is preparation, so much is routine, and so much retrospect, that the pith of each man’s genius contracts itself to a very few hours. Paraphrase: These fleeting, extraordinary moments make ordinary life seem trivial by comparison, and we rarely recognize or record them. Even acts of heroism or martyrdom appear small or insignificant while we are living through them. Romance and adventure feel vivid and compelling when observed from afar, but as soon as we are directly involved — the ship we sail on — the magic often fades. Life, in our own experience, feels mundane, while elsewhere the world is alive with wonder. He gives an example of human jealousy and comparison. A complaining farmer observes that his neighbor has lush, productive fields while his own seems bare, able only to “hold the world together.” Emerson wryly notes that people often borrow or repeat each other’s complaints, and in turn, everyone’s contributions and efforts can feel diminished. Nature, he suggests, has a way of “degrading” the present day: much activity, noise, and effort seem insignificant, while the true results often appear unexpectedly, almost magically, elsewhere. Life’s hidden complexities continue on a personal level. At first glance, everything — like a house or a roof — may appear orderly and pleasant. But when we look closer, we often uncover suffering: grieving women, stern husbands, the burdens of daily life, and the slow wash of forgetfulness (“lethe”) that erases memory or awareness. The visible surface of life only hints at its true depth. Human activity is vast, but so much of it is routine, preparatory, or retrospective. The core of each person’s creative or intellectual power — the “pith of genius” — is concentrated in only a few moments, while the rest of life passes in repetition, observation, or waiting. Glossary “What’s the news?” — People casually ask for updates as though only new events matter, implying that the past (“the old”) is unimportant or worthless. “As if the old were so bad” — Emerson wryly points out that this attitude dismisses all the lessons, depth, and significance already present in life; people ignore the richness of what has already happened. “How many individuals…actions…opinions?” — He emphasizes that society is vast and complex. Even counting all the people, their deeds, and their ideas, we are overwhelmed. Most of it goes unnoticed, unrecorded, or unappreciated. In short: People tend to focus on novelty while overlooking the depth, continuity, and accumulated wisdom of life. Emerson is critiquing society’s shallow attention and the illusion that only the “new” matters. “’Tis the trick of nature” — Nature (or life itself) has a way of hiding its true workings; things rarely seem important or significant while they are happening. “to degrade to-day” — The present moment often feels small, insignificant, or messy, compared to the way results or meaning appear later. “a good deal of buzz” — Lots of activity, noise, or effort seems superficial or unproductive. “somewhere a result slipped magically in” — Despite the apparent chaos or triviality, important outcomes, growth, or effects quietly happen behind the scenes, almost as if by magic. In short: Life may seem busy, messy, or insignificant as it unfolds, but meaningful results are still happening — often in ways we don’t immediately see. Emerson is pointing out the hidden efficiency and subtle creativity of nature and human life. Modern connection We notice magic more easily in others’ lives than in our own — yet Emerson reminds us that significant impact and genius are concentrated, often hidden in the few decisive moments we take seriously. Like the farmer, we may be tempted to measure ourselves against others, forgetting that life’s value is not always obvious in real time. Moments of meaning or creativity usually appear unexpectedly, quietly shaping the future. Think of the countless small, unnoticed efforts at work in any project, relationship, or social movement. At the moment, everything can feel chaotic, messy, or meaningless — but outcomes often emerge quietly, sometimes unexpectedly, like a breakthrough or insight that seems almost “magical” in hindsight. It reminds us to trust the unseen processes at work in life. Paragraph 9. The history of literature—take the net result of Tiraboschi, Warton, or Schlegel—is a sum of very few ideas and of very few original tales; all the rest being variation of these. So in this great society wide-lying around us, a critical analysis would find very few spontaneous actions. It is almost all custom and gross sense. There are even few opinions, and these seem organic in the speakers, and do not disturb the universal necessity. Paragraph 10. What opium is instilled into all disaster! It shows formidable as we approach it, but there is at last no rough rasping friction, but the most slippery sliding surfaces. We fall soft on a thought; Ate Dea is gentle,— “Over men’s heads walking aloft, People grieve and bemoan themselves, but it is not half so bad with them as they say. There are moods in which we court suffering, in the hope that here at least we shall find reality, sharp peaks and edges of truth. But it turns out to be scene-painting and counterfeit. Paragraph 11. The only thing grief has taught me is to know how shallow it is. That, like all the rest, plays about the surface, and never introduces me into the reality, for contact with which we would even pay the costly price of sons and lovers. Paraphrase: He extends this observation to human society: even in a vast community, spontaneous, genuinely creative actions are uncommon. Most behavior follows established custom or basic practical sense. Opinions exist, but they are deeply shaped by the person expressing them and rarely challenge the greater patterns or necessities of life. In other words, much of what we think is innovative or independent is actually shaped by the same universal forces governing everyone. Emerson then turns to the way humans experience misfortune. He likens disaster to a kind of opium: it seems terrifying as we approach it, but in reality, it is softer and less harmful than it first appears. We glide through difficulties without the harsh friction we anticipate, landing gently on insights or experiences that feel profound. People often exaggerate their suffering, believing that grief will reveal ultimate truths. They hope to find sharp, unvarnished reality in pain — the “edges” of truth — but Emerson notes that these experiences often turn out to be more like a painted scene or imitation, rather than the deep revelation they expect. He concludes that grief itself teaches a surprising lesson: it is shallow. Like many other experiences we overvalue, grief skims the surface of reality without granting us direct access to its depths. The intense encounters we imagine — those for which we might give up family, love, or safety — rarely penetrate fully into the essence of existence. Life’s true reality remains largely hidden, even in moments we consider most revealing. Glossary

he is ironically noting that what we expect to be destructive or painful — misfortune, ruin, or grief — often comes softly, almost imperceptibly, rather than with dramatic force. Emerson is emphasizing how human suffering is less harsh and more subtle than we imagine; the “god of mischief” moves lightly, not with the terrifying weight we anticipate. Modern connection:

Paragraph 12. Was it Boscovich who found out that bodies never come in contact? Well, souls never touch their objects. An innavigable sea washes with silent waves between us and the things we aim at and converse with. Paragraph 13. Grief too will make us idealists. In the death of my son, now more than two years ago, I seem to have lost a beautiful estate,—no more. I cannot get it nearer to me. Paragraph 14. If to-morrow I should be informed of the bankruptcy of my principal debtors, the loss of my property would be a great inconvenience to me, perhaps, for many years; but it would leave me as it found me,—neither better nor worse. So is it with this calamity: something which I fancied was a part of me, which could not be torn away without tearing me nor enlarged without enriching me, falls off from me and leaves no scar. It was caducous. Paraphrase: No matter how close we believe ourselves to be to people, possessions, or aims, there is always a silent, uncrossable distance between us and them, like an unnavigable sea separating us from what we pursue.

Grief itself makes this truth clear. In the death of his son more than two years earlier, Emerson feels as though he lost a beautiful estate—something precious that once belonged to him, but which now exists only as something removed and unreachable. He cannot draw it closer or recover it inwardly. If he were to lose his wealth through the bankruptcy of those who owe him money, the loss would inconvenience him for years, but it would not alter his essential being. He would remain fundamentally the same. He realizes that the same is true of this deeper calamity: something he once believed was an inseparable part of himself, something whose loss should have torn his very nature, has fallen away cleanly, leaving no lasting wound. What he assumed was integral to his being turns out to have been temporary and perishable. Glossary: Modern connection: Paragraph 15. I grieve that grief can teach me nothing, nor carry me one step into real nature. Paragraph 16. The Indian who was laid under a curse that the wind should not blow on him, nor water flow to him, nor fire burn him, is a type of us all. Paragraph 17. The dearest events are summer-rain, and we the Para coats that shed every drop. Nothing is left us now but death. Paragraph 18. We look to that with a grim satisfaction, saying, There at least is reality that will not dodge us. Paragraph 19. I take this evanescence and lubricity of all objects, which lets them slip through our fingers then when we clutch hardest, to be the most unhandsome part of our condition. Nature does not like to be observed, and likes that we should be her fools and playmates. Paragraph 20. We may have the sphere for our cricket-ball, but not a berry for our philosophy. Direct strokes she never gave us power to make; all our blows glance, all our hits are accidents. Our relations to each other are oblique and casual. Paraphrase: We even look to death with a grim satisfaction, because it is at least real and cannot evade us. The hardest part of our human condition is how everything slips away just as we try to grasp it most firmly. Nature resists being fully observed or controlled and prefers that we be her playful companions rather than serious examiners. In action, we may strike directly, but in thought, philosophy, and understanding, our efforts never land cleanly; successes are accidental, our blows glance off, and our relationships with each other remain indirect, oblique, and contingent. Glossary Modern connection Paragraph 21. Dream delivers us to dream, and there is no end to illusion. Paragraph 22. Life is a train of moods like a string of beads, and as we pass through them they prove to be many-colored lenses which paint the world their own hue, and each shows only what lies in its focus. Paragraph 23. From the mountain you see the mountain. We animate what we can, and we see only what we animate. Paragraph 24. Nature and books belong to the eyes that see them. It depends on the mood of the man whether he shall see the sunset or the fine poem. Paragraph 25. The subject exists, the subject enlarges; all things, sooner or later, fall into place. Why should we hurry to fill our hours with schemes, when all is so slowly and perfectly organized? All experience is an arch wherethrough we pass, but which obstructs the prospect. The eternal life lies behind us, and before us; but we are not yet at home. Paraphrase: Life unfolds as a series of moods, like beads on a string, and each mood acts as a colored lens, casting its own hue over the world and revealing only what falls within its focus. From the mountain, we see the mountain; we perceive and give life only to what we can animate, and our vision is shaped by our own activity. Nature and books belong to the eyes that behold them: whether we see the brilliance of a sunset or the subtle beauty of a poem depends entirely on our mood. Subjects expand as we engage with them, and eventually, all things fall into their proper place. There is no need to rush through life filling hours with plans and schemes, for everything is slowly and perfectly arranged. All experience forms an arch through which we pass, sometimes obscuring the larger view, while the eternal life lies both behind and ahead; yet, for now, we are not truly at home. Glossary Modern connection By cultivating awareness and patience, we can recognize that every experience, no matter how small, contributes to a larger, coherent flow of life—even if we do not yet feel fully “at home” in it. Paragraph 26. As I am, so I see; use what language we will, we can never say anything but what we are. What we are, that only can we see. All that Adam had, all that Caesar could, you have and can do. Adam called his house, heaven and earth; Caesar called his house, Rome; you perhaps call yours a cobbler’s trade;—but they are all the same house. Paragraph 27. There are moods in which we court suffering, in the hope that here, at least, we shall find reality, sharp peaks and edges of truth. But it turns out to be scene-painting and counterfeit. The only thing grief has taught me is to know how shallow it is. Paragraph 28. People forget that it is the eye which makes the horizon, and the rounding mind’s eye which makes this or that man a type or representative of humanity with the name of hero or saint. Jesus the “provident,” Confucius the “circumspect,” Epaminondas the “modest,” are they not parts of our own souls? Paragraph 29. We live amid surfaces, and the true art of life is to skate well on them. Under the hardest exterior, there is an inward softness. Every moment instructs, and every object: for wisdom is infused into every form. Paragraph 30. It is not new facts that avail, but the heat to dissolve everybody’s facts. The value of any fact is its susceptibility of being expanded. The atom is as large as the world, when its affinities are considered. Paraphrase: Our vision is shaped by our own nature, and all that past figures like Adam or Caesar could do, we too can do. Adam called his domain heaven and earth, Caesar called his Rome, and you may call yours a humble trade—but they are all the same human “house,” shaped by the mind that inhabits it. There are moods in which we seek suffering, hoping to find sharp, undeniable truth in grief, but even there we encounter only illusion and superficial scene-painting; grief teaches only how shallow it is. People forget that the horizon is made by the eye, and that the mind’s vision shapes heroes, saints, and types of humanity; figures like Jesus, Confucius, and Epaminondas are extensions of our own souls.

Life is lived on surfaces, and the art of living is to move gracefully over them; beneath the hardest exterior lies inward softness, and every moment and object instructs us, for wisdom is woven into every form. True insight does not come from accumulating new facts, but from the ability to expand and interconnect them; even the smallest atom contains the potential of the world when its relationships are fully understood. Glossary Modern connection Life offers lessons everywhere, if we can move with awareness over the surface of events while recognizing the depth beneath. True understanding comes not from collecting isolated facts, but from seeing how everything connects, from the smallest detail to the largest pattern. Everyone has the potential to shape and inhabit their “house” in life fully, just as history’s great figures did, if they recognize the power within themselves. Paragraph 31. Man lives by belief. Belief is the creative force in him. If he believe that he can do no good, he will do none. If he believe that he is poor, he will always remain so. Paragraph 32. The mind is no match for matter in movement, but it is in command of its own world. It is not defeated by defeat. It rises from its ashes. All things are possible to it. Paragraph 33. Temperament is the iron wire on which the beads are strung. It is the bias of the individual. Every man is born with a bent which irresistibly determines his behavior. Paragraph 34. We cannot escape our nature. We may for a time succeed in deceiving ourselves, but sooner or later the old law reappears. We walk on by law, and cannot turn aside. Paragraph 35. The lesson of life is not to be learned by dramatic examples. We need not be heroes or saints to know the truth. The common day is rich with instruction. Paraphrase: The mind may not control the external world directly, but it governs its own realm. It is never truly defeated and can rise from every setback, for within it all things are possible. Each person is born with a temperament, an inner “iron wire” that guides and shapes their behavior, forming a natural bias or inclination. We cannot escape our fundamental nature; even if we deceive ourselves temporarily, life’s laws will eventually assert themselves. We move forward according to these laws and cannot permanently turn aside. The lessons of life are not learned through dramatic, extraordinary examples, but through the ordinary moments of daily experience, which are full of instruction for those who observe. Glossary Modern connection True strength comes from understanding and managing the mind, not from controlling everything outside. Everyone has innate tendencies, and life’s laws will ultimately guide us, regardless of temporary illusions or self-deception. The richest lessons are often found in simple, everyday experiences rather than in dramatic or extraordinary events. Paragraph 36. We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us organs of its activity, and receivers of its truth. When we are willing to be instruments, we learn. Paragraph 37. Let us be silent, that we may hear the whisper of the gods. Let us be humble, that we may be exalted. Paragraph 38. There is victory yet for all justice; and the true romance which the world exists to realize will be the transformation of genius into practical power. Paragraph 39. The future is not something that comes to us; it is something we enter. We create it by our conduct. Paragraph 40. Patience and patience, we shall win at the last. The law of the universe is not mocked. What we sow, we reap. Paragraph 41. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star. Paraphrase: When we are willing to act as channels, we are able to learn and grow. Silence allows us to hear the subtle guidance of the divine, and humility opens the way for true elevation. Justice will ultimately prevail, and the world’s highest purpose is the transformation of individual genius into practical, positive power. The future is not something that happens to us passively; we actively create it through our actions and choices. Patience is essential, for in time we will achieve what is right—what we sow, we shall reap, and the laws of the universe cannot be evaded. Only the day for which we are awake truly dawns; there is always more light and opportunity ahead, for the sun itself is just the morning star of a greater day to come. Glossary Modern connection Our actions shape the future, and patience is essential because the universe operates according to cause and effect. Progress and growth come from actively participating, transforming ideas into practical results, and staying awake to the potential in each moment. Even small beginnings carry the promise of much larger achievements. Brief summary of the entire essay Emerson begins by noting humanity’s inability to see its place on life’s “staircase,” unable to perceive fully the vast order and connections of the universe. He emphasizes that everything in the universe is linked, and that every form, color, and event communicates meaning to those who observe attentively. Life is full of fleeting moments and illusions, and our perception is shaped by mood, belief, and temperament. Grief, suffering, and ordinary experiences teach lessons if we remain aware, while true understanding comes from observing the world with humility and patience rather than through dramatic or extraordinary events. Human perception shapes reality itself: horizons, heroes, and history are reflected through our minds, and greatness exists in part because it mirrors qualities in our own souls. Belief, imagination, and attention give the mind creative power, allowing us to rise above apparent limitations and transform genius into practical action. While we cannot escape the laws of the universe, we can act as instruments of its intelligence, cultivating silence, attentiveness, and moral awareness. Ultimately, Emerson urges us to live fully awake, participate consciously in the unfolding of life, and recognize that even ordinary moments carry profound lessons, while the universe steadily unfolds its order and promise.

|

||||||

|

|