|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

return to "Happiness" main-page

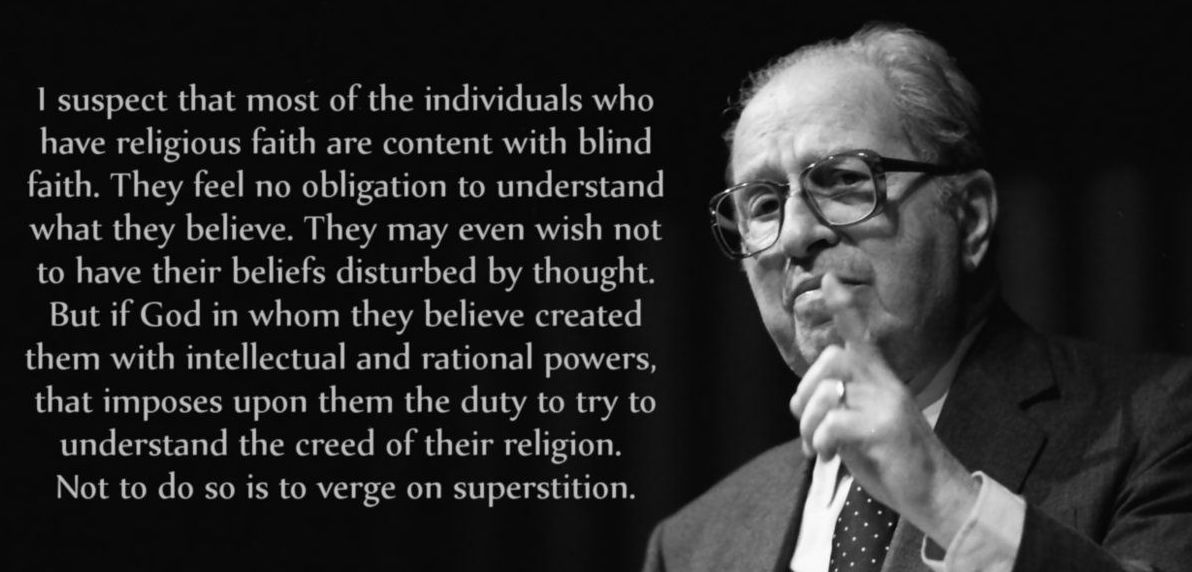

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler (1902 - 2001)

On all these questions, the great books set forth the fundamental inquiries and speculations, as well as the controversies to which they have given rise, in the tradition of western thought. There seems to be no question that men want happiness.

To the question, what moves desire? Locke thinks only one answer is possible: "happiness, and that alone." But this fact, even if it goes undisputed, does not settle the issue whether men are right in governing their lives with a view to being or becoming happy. There is therefore one further question.

According to Kant, "the principle of private happiness" is "the direct opposite of the principle of morality."

What Kant calls the "pragmatic" rule of life, which aims at happiness, "tells us what we have to do, if we wish to become possessed of happiness." Unlike the moral law, it is a hypothetical, not a categorical, imperative. Furthermore, Kant points out that such a pragmatic or utilitarian ethics (which is for him the same as an "ethics of happiness") cannot help being empirical, "for it is only by experience," he says, "that I can learn either what inclinations exist which desire satisfaction, or what are the natural means of satisfying them." Such empirical knowledge "is available for each individual in his own way." Hence there can be no universal solution in terms of desire of the problem of how to be happy. To reduce moral philosophy to "a theory of happiness" must result, therefore, in giving up the search for ethical principles which are both universal and a priori. In sharp opposition to the pragmatic rule, Kant sets the "moral or ethical law," the motive of which is not simply to be happy, but rather to be worthy of happiness. In addition to being a categorical imperative which imposes an absolute obligation upon us, this law, he says, "takes no account of our desires or the means of satisfying them." Rather it "dictates how we ought to act in order to deserve happiness." It is drawn from pure reason, not from experience, and therefore has the universality of an a priori principle, without which, in Kant's opinion, a genuine science of ethics -- or metaphysic of morals -- is impossible. With the idea of moral worth--that which alone deserves happiness--taken away, "happiness alone is," according to Kant, "far from being the complete good. Reason does not approve of it (however much inclination may desire it) except as united with desert. On the other hand," Kant admits, "morality alone, and, with it, mere desert, is likewise far from being the complete good." These two things must be united to constitute the true summum bonum which, according to Kant, means both the supreme and the complete good. The man "who conducts himself in a manner not unworthy of happiness, must be able to hope for the possession of happiness." But even if happiness combined with moral worth does constitute the supreme good, Kant still refuses to admit that happiness, as a practical objective, can function as a moral principle.

In other words, happiness fails for Kant to impose any moral obligation or to provide a standard of right and wrong in human conduct. No more than pleasure can happiness be used as a first principle in ethics, if morality must avoid all calculations of utility or expediency whereby things are done or left undone for the sake of happiness, or any other end to be enjoyed. THIS ISSUE BETWEEN an ethics of duty and an ethics of happiness, as well as the conflict it involves between law and desire as sources of morality, are considered, from other points of view, in the chapters on DESIRE and DUTY, and again in GOOD AND EVIL where the problem of the summum bonum is raised. In this chapter, we shall be concerned with happiness as an ethical principle, and therefore with the problems to be faced by those who, in one way or another, accept happiness as the supreme good and the end of life. They may see no reason to reject moral principles which work through desire rather than duty. They may find nothing repugnant in appealing to happiness as the ultimate end which justifies the means and determines the order of all other goods. But they cannot make happiness the first principle of ethics without having to face many questions concerning the nature of happiness and its relation to virtue.

Once they have asserted that fact, once they have made happiness the most fundamental of all ethical terms, writers like Aristotle or Locke, Aquinas or J. S. Mill, cannot escape the question whether all who seek happiness look for it or find it in the same things. Holding that a definite conception of happiness cannot be formulated, Kant thinks that happiness fails even as a pragmatic principle of conduct. "The notion of happiness is so indefinite," he writes, "that although every man wishes to attain it, yet he never can say definitely and consistently what it is that he really wishes."

Locke plainly asserts what is here implied, namely, the fact that "everyone does not place his happiness in the same thing, or choose the same way to it." But admitting this fact does not prevent Locke from inquiring how "in matters of happiness and misery. . . men come often to prefer the worse to the better; and to choose that which, by their own confession, has made them miserable." Even though he declares that "the same thing is not good to every man alike," Locke thinks it is possible to account "for the misery that men often bring on themselves" by explaining how the individual may make errors in judgment -- "how things come to be represented to our desires under deceitful appearances . . . by the judgment pronouncing wrongly concerning them." But this applies to the individual only. Locke does not think it is possible to show that when two men differ in their notions of happiness, one is right and the other wrong. "Though all men's desires tend to happiness, yet they are not moved by the same object. Men may choose different things, and yet all choose right." He does not quarrel with the theologians who, on the basis of divine revelation, describe the eternal happiness in the life hereafter which is to be enjoyed alike by all who are saved. But revelation is one thing, and reason another. With respect to temporal happiness on earth, reason cannot achieve a definition of the end that has the certainty of faith concerning salvation. Hence Locke quarrels with "the philosophers of old" who, in his opinion, vainly sought to define the summum bonum or happiness in such a way that all men would agree on what happiness is; or, if they failed to, some would be in error and misled in their pursuit of happiness. It may be wondered, therefore, what Locke means by saying that there is a science of what man ought to do "as a rational and voluntary agent for the attainment of . . . happiness." He describes ethics as the science of the "rules and measures of human actions, which lead to happiness" and he places "morality amongst the sciences capable of demonstration, wherein ... from self-evident propositions, by necessary consequences, as incontestable as those in mathematics, the measures of right and wrong might be made out, to any one that will apply himself with the same indifferency and attention to the one, as he does to the other of these sciences."

Happiness is not that principle if the content of happiness is what each man thinks it to be; for if no universally applicable definition of happiness can be given -- if when men differ in their conception of what constitutes happiness, one man may be as right as another -- then the fact that all men agree upon giving the name "happiness" to what they ultimately want amounts to no more than a nominal agreement. Such nominal agreement, in the opinion of Aristotle and Aquinas, does not suffice to establish a science of ethics, with rules for the pursuit of happiness which shall apply universally to all men.

It may be granted that there are in fact many different opinions about what constitutes happiness, but it cannot be admitted that all are equally sound without admitting a complete relativism in moral matters. Erasmus, in Praise of Folly, has Folly argue for such relativism: "What difference is there, do you think, between those in Plato's cave who can only marvel at the shadows and images of various objects, provided they are content and don't know what they miss, and the philosopher who has emerged from the cave and sees the real things? If Mycillus in Lucian had been allowed to go on dreaming that golden dream of riches for evermore, he'd have had no reason to desire any other state of happiness."

That men do in fact seek different things under the name of happiness does not, according to Aristotle and Aquinas, alter the truth that the happiness they should seek must be something appropriate to the humanity which is common to them all, rather than something determined by their individually differing needs or temperaments. If it were the latter, then Aristotle and Aquinas would admit that questions about what men should do to achieve happiness would be answerable only by individual opinion or personal preference, not by scientific analysis or demonstration. With the exception of Locke and perhaps to a less extent Mill, those who think that a science of ethics can be founded on happiness as the first principle tend to maintain that there can be only one right conception of human happiness.

Other notions are misconceptions that may appear to be, but are not really, the totum bonum. The various definitions of happiness which men have given thus present the problem of the real and the apparent good, the significance of which is considered in the chapter on GOOD AND EVIL. IN THE EVERYDAY discourse of men there seems to be a core of agreement about the meaning of the words "happy" and "happiness." This common understanding has been used by philosophers like Aristotle and Mill to test the adequacy of any definition of happiness. When a man says "I feel happy" he is saying that he feels pleased or satisfied -- that he has what he wants. When men contrast tragedy and happiness, they have in mind the quality a life takes from its end. A tragedy on the stage, in fiction, or in life is popularly characterized as "a story without a happy ending."

There appears to be some conflict here between being happy at a given moment and being happy for a lifetime, that is, living happily.

Nevertheless, in both uses of the word "happy" there is the connotation of satisfaction.

If they are asked why they want to be happy, they find it difficult to give any reason except "for its own sake." They can think of nothing beyond happiness for which happiness serves as a means or a preparation. This aspect of ultimacy or finality appears without qualification in the sense of happiness as belonging to a whole life. There is quiescence, too, in the momentary feeling of happiness, but precisely because it does not last, it leaves another and another such moment to be desired. Observing these facts, Aristotle takes the word "happiness" from popular discourse and gives it the technical significance of ultimate good, last end, or summum bonum.

The ultimacy of happiness can also be expressed in terms of its completeness or sufficiency. It would not be true that happiness is desired for its own sake and everything else for the sake of happiness, if the happy man wanted something more.

It is this insight which Boethius later expresses in an oft-repeated characterization of happiness as "a life made perfect by the possession in aggregate of all good things."

"If happiness were to be counted as one good among others," Aristotle argues, "it would clearly be made more desirable by the addition of even the least of goods." But then there would be something left for the happy man to desire, and happiness would not be "something final and self-sufficient and the end of action." Like Aristotle, Mill appeals to the common sense of mankind for the ultimacy of happiness. "The utilitarian doctrine," he writes, "is that happiness is desirable, and the only thing desirable as an end; all other things being only desirable as means." No reason can or need be given why this is so, "except that each person, so far as he believes it to be attainable, desires his own happiness." This is enough to prove that happiness is a good. To show that it is the good, it is "necessary to show, not only that people desire happiness, but that they never desire anything else." Here Mill's answer, like Aristotle's, presupposes the rightness of the prevailing sense that when a man is happy, he has everything he desires. Many things, Mill admits, may be desired for their own sake, but if the possession of any one of these leaves something else to be desired, then it is desired only as a part of happiness. Happiness is "a concrete whole, and these are some of its parts . . . Whatever is desired otherwise than as a means to some end beyond itself, and ultimately to happiness, is desired as itself a part of happiness, and is not desired for itself until it has become so." THERE ARE OTHER conceptions of happiness. It is not always approached in terms of means and ends, utility and enjoyment or satisfaction.

Early in The Republic, Socrates is challenged to show that the just man will be happier than the unjust man, even if in all externals he seems to be at a disadvantage. He cannot answer this question until he prepares Glaucon for the insight that justice is "concerned not with the outward man, but with the inward." He can then explain that "the just man does not permit the several elements within him to interfere with one another . . . He sets in order his own inner life, and is his own master and his own law, and is at peace with himself." In the same spirit Plotinus asks us to think of "two wise men, one of them possessing all that is supposed to be naturally welcome, while the other meets only with the very reverse." He wants to know whether we would "assert that they have an equal happiness." His own answer is that we should, "if they are equally wise . . . [even] though the one be favored in body and in all else that does not help towards wisdom." We are likely to misconceive happiness, Plotinus thinks, if we consider the happy man in terms of our own feebleness. "We count alarming and grave what his felicity takes lightly; he would be neither wise nor in the state of happiness if he had not quitted all trifling with such things." According to Plotinus, "Plato rightly taught that he who is to be wise and to possess happiness draws his good from the Supreme, fixing his gaze on That, becoming like to That, living by That... All else he will attend to only as he might change his residence, not in expectation of any increase in his settled felicity, but simply in a reasonable attention to the differing conditions surrounding him as he lives here or there." If he "meets some turn of fortune that he would not have chosen, there is not the slightest lessening of his happiness for that."

The opposite view is more frequently held. In his argument with Callicles in the Gorgias, Socrates meets with the proposition that it is better to injure others than to be injured by them. This can be refuted, he thinks, only if Callicles can be made to understand that the unjust or vicious man is miserable in himself, regardless of his external gains.

This association of happiness with health - the one a harmony in the soul as the other is a harmony in the body - appears also in Freud's consideration of human well-being. For Freud, the ideal of health, not merely bodily health but the health of the whole man, seems to identify happiness with peace of mind. "Anyone who is born with a specially unfavorable instinctual constitution," he writes, "and whose libido-components do not go through the transformation and modification necessary for successful achievement in later life, will find it hard to obtain happiness." The opposite of happiness is not tragedy but neurosis. In contrast to the neurotic, the happy man has found a way to master his inner conflicts and to become well-adjusted to his environment. The theory of happiness as mental health or spiritual peace may be another way of seeing the self-sufficiency of happiness, in which all striving comes to rest because all desires are fulfilled or quieted. The suggestion of this point is found in the fact that the theologians conceive beatitude, or supernatural happiness, in both ways. For them it is both an ultimate end which satisfies all desires and also a state of peace or heavenly rest. The ultimate good, Augustine writes, "is that for the sake of which other things are to be desired, while it is to be desired for its own sake"; and, he adds, it is that by which the good "is finished, so that it becomes complete" - all-satisfying. But what is this "final blessedness, the ultimate consummation, the unending end"? It is peace. "Indeed," Augustine says, "we are said to be blessed when we have such peace as can be enjoyed in this life; but such blessedness is mere misery compared to that final felicity," which can be described as "either peace in eternal life or eternal life in peace." THERE MAY BE differences of another kind among those who regard happiness as their ultimate end. Some men identify happiness with the possession of one particular type of good - wealth or health, pleasure or power, knowledge or virtue, honor or friendship - or, if they do not make one or another of these things the only component of happiness, they make it supreme. The question of which is chief among the various goods that constitute the happy life is the problem of the order of goods, to which we shall return presently. But the identification of happiness with some one good, to the exclusion or neglect of the others, seems to violate the meaning of happiness on which there is such general agreement. Happiness cannot be that which leaves nothing to be desired if any good - anything which is in any way desirable - is overlooked. But it may be said that the miser desires nothing but gold, and considers himself happy when he possesses a hoard. That he may consider himself happy cannot be denied. Yet this does not prevent the moralist from considering him deluded and in reality among the unhappiest of men. The difference between such illusory happiness and the reality seems to depend on the distinction between conscious and natural desire. According to that distinction, considered in the chapter on DESIRE, the miser may have all that he consciously desires, but lack many of the things toward which his nature tends and which are therefore objects of natural desire. He may be the unhappiest of men if, with all the wealth in the world, yet self-deprived of friends or knowledge, virtue or even health, his exclusive interest in one type of good leads to the frustration of many other desires. He may not consciously recognize these, but they nevertheless represent needs of his nature demanding fulfillment. As suggested in the chapter on DESIRE, the relation of natural law to natural desire may provide the beginning, at least, of an answer to Kant's objection to the ethics of happiness on the ground that its principles lack universality or the element of obligation. The natural moral law may command obedience at the same time that it directs men to happiness as the satisfaction of all desires which represent the innate tendencies of man's nature. The theory of natural desire thus also has a bearing on the issue whether the content of happiness must really be the same for all men, regardless of how it may appear to them. Even if men do not identify happiness with one type of good, but see it as the possession of every sort of good, can there be a reasonable difference of opinion concerning the types of good which must be included or the order in which these several goods should be sought? A negative answer seems to be required by the view that real as opposed to apparent goods are the objects of natural desire. Aquinas, for example, admits that "happy is the man who has an he desires, or whose every wish is fulfilled, is a good and adequate definition" only "if it be understood in a certain way." It is "an inadequate definition if understood in another. For if we understand it simply of all that man desires by his natural appetite, then it is true that he who has all that he desires is happy; since nothing satisfies man's natural desire, except the perfect good which is Happiness. But if we understand it of those things that man desires according to the apprehension of reason," Aquinas continues, then "it does not belong to Happiness to have certain things that man desires; rather does it belong to unhappiness, in so far as the possession of such things hinders a man from having all that he desires naturally." For this reason, Aquinas points out, when Augustine approved the statement that "happy is he who has all he desires," he added the words "provided he desires nothing amiss." As men have the same complex nature, so they have the same set of natural desires. As they have the same natural desires, so the real goods which can fulfill their needs comprise the same variety for all. As different natural desires represent different parts of human nature - lower and higher - so the several kinds of good are not equally good. And, according to Aquinas, if the natural object of the human will "is the universal good," it follows that "naught can satisfy man's will save the universal good." This, he holds, "is to be found, not in any created thing, but in God alone." We shall return later to the theologian's conception of perfect happiness as consisting in the vision of God in the life hereafter. The happiness of this earthly life (which the philosopher considers) may be imperfect by comparison, but such temporal felicity as men can attain is no less determined by natural desire. If a man's undue craving for one type of good can interfere with his possession of another sort of good, then the various goods must be ordered according to their worth; and this order, since it reflects natural desire, must be the same for all men. In such terms Aristotle seems to think it possible to argue that the reality of happiness can be defined by reference to human nature and that the rules for achieving happiness can have a certain universality- despite the fact that the rules must be applied by individuals differently to the circumstances of their own lives. No particular good should be sought excessively or out of proportion to others, for the penalty of having too much of one good thing is deprivation or disorder with respect to other goods. THE RELATION OF happiness to particular goods raises a whole series of questions, each peculiar to the type of good under consideration. Of these, the most insistent problems concern pleasure, knowledge, virtue, and the goods of fortune. With regard to pleasure, the difficulty seems to arise from two meanings of the term which are more fully discussed in the chapter on PLEASURE AND PAIN. In one of these meanings pleasure is an object of desire, and in the other it is the feeling of satisfaction which accompanies the possession of objects desired. It is in the latter meaning that pleasure can be identified with happiness or, at least, be regarded as its correlate, for if happiness consists in the possession of all good things it is also the sum total of attainable satisfactions or pleasures. Where pleasure means satisfaction, pain means frustration, not the sensed pain of injured flesh. Happiness, Locke can therefore say, "is the utmost pleasure we are capable of"; and Mill can define it as "an existence exempt as far as possible from pain, and as rich as possible in enjoyments." Nor does Aristotle object to saying that the happy life "is also in itself pleasant." But unlike Locke and Mill, Aristotle raises the question whether all pleasures are good, and all pains evil. Sensuous pleasure as an object often conflicts with other objects of desire. And if "pleasure" means satisfaction, there can be conflict among pleasures, for the satisfaction of one desire may lead to the frustration of another. At this point Aristotle finds it necessary to introduce the principle of virtue. The virtuous man is one who finds pleasure "in the things that are by nature pleasant." The virtuous man takes pleasure only in the right things, and is willing to suffer pain for the right end. If pleasures, or desires and their satisfaction, can be better or worse, there must be a choice among them for the sake of happiness. Mill makes this choice depend on a discrimination between lower and higher pleasures, not on virtue. He regards virtue merely as one of the parts of happiness, in no way different from the others. But Aristotle seems to think that virtue is the principal means to happiness because it regulates the choices which must be rightly made in order to obtain all good things; hence his definition of happiness as "activity in accordance with virtue." This definition raises difficulties of still another order. As the chapter on VIRTUE AND VICE indicates, there are for Aristotle two kinds of virtue, moral and intellectual, the one concerned with desire and social conduct, the other with thought and knowledge. There are also two modes of life, sometimes called the active and the contemplative, differing as a life devoted to political activity or practical tasks differs from a life occupied largely with theoretical problems in the pursuit of truth or in the consideration of what is known. Are there two kinds of happiness then, belonging respectively to the political and the speculative life? Is one a better kind of happiness than another? Does the practical sort of happiness require intellectual as well as moral virtue? Does the speculative sort require both also? In trying to answer these questions, and generally in shaping his definition of happiness, Aristotle considers the role of the goods of fortune, such things as health, wealth, auspicious birth, native endowments of body or mind, and length of life. These gifts condition virtuous activity or may present problems which virtue is needed to solve. But to the extent that having or not having them is a matter of fortune, they are not within a man's control - to get, keep, or give up. If they are indispensable, happiness is precarious, or even unattainable by those who are unfortunate. In addition, if the goods of fortune are indispensable, the definition of happiness must itself be qualified. More is required for happiness than activity in accordance with virtue. "Should we not say," Aristotle asks, "that he is happy who is active in accordance with complete virtue and is sufficiently equipped with external goods, not for some chance period but throughout a complete life? Or must we add 'and who is destined to live thus and die as befits his life'?. . . If so, we shall call happy those among living men in whom these conditions are, and are to be, fulfilled - but happy men." THE CONSIDERATION of the goods of fortune has led to diverse views about the attainability of happiness in this life. For one thing, they may act as an obstacle to happiness. Pierre Bezukhov in War and Peace learned, during his period of captivity, that "man is created for happiness; in himself, in the satisfaction of his natural cravings; that all unhappiess arises not from privation but from superfluity." The vicissitudes of fortune seem to be what Solon has in mind when, as reported by Herodotus, he tells Croesus, the king of Lydia, that he will not call him happy "until I hear that thou has closed thy life happily ... for oftentimes God gives men a gleam of happiness, and then plunges them into ruin." For this reason, in judging of happiness, as "in every matter, it behoves us to mark well the end." Even if it is possible to call a man happy while he is alive - on the ground that virtue, which is within his power, may be able to withstand anything but the most outrageous fortune - it is still necessary to define happiness by reference to a complete life. Children cannot be called happy, Aristotle holds, because their characters have not yet matured and their lives are still too far from completion. To call them happy, or to call happy men of any age who still may suffer great misfortune, is merely to voice the hopes we have for them. "The most prosperous," Aristotle writes, "may fall into great misfortunes in old age, as is told of Priam in the Trojan cycle; and one who has experienced such chances and has ended wretchedly no one calls happy." Among the goods of fortune which seem to have a bearing on the attainment of happiness, those which constitute the individual nature of a human being at birth - physical traits, temperament, degree of intelligence - may be unalterable in the course of life. If certain inherited conditions either limit the capacity for happiness or make it completely unattainable, then happiness, which is defined as the end of man, is not the summum bonum for all, or not for all in the same way. In the Aristotelian view, for example, women cannot be happy to the same degree or in the same manner as men; and natural slaves, like beasts, have no capacity for happiness at all, participate in the happiness of the masters they serve. The theory is that through serving him, the slave gives the master the leisure necessary for the political or speculative life open to those of auspicious birth. Even as the man who is a slave belongs wholly to another man, so the highest good of his life lies in his contribution to the happiness of that other. The question whether happiness can be achieved by all normal human beings or only by those gifted with very special talents, depends for its answer in part on the conception of happiness itself. Like Aristotle, Spinoza places happiness in intellectual activity of so high an order that the happy man is almost godlike; and, at the very end of his Ethics, he finds it necessary to say that the way to happiness "must indeed be difficult since it is so seldom discovered." Nevertheless, "true peace of soul" can be found by the rare individual. "All noble things are as difficult as they are rare." In contrast, a statement like Tawney's - that "if a man has important work to do, and enough leisure and income to enable him to do it properly, he is in possession of as much happiness as is good for any of the children of Adam" seems to make happiness available to more than the gifted few. Whether happiness is attainable by all men, even on Tawney's definition, may also depend on the economic system and the political constitution, to the extent that they determine whether all men will be granted the opportunity and the leisure to use whatever talents they have for leading a decent human life. There seems to be a profound connection between conceiving happiness in such a way that all normal men are capable of it and insisting that all normal men deserve political status and economic liberty. Mill, for example, differs from Aristotle on both scores. DIFFERING FROM the position of both Aristotle and Mill is the view that happiness is an illusory goal - that the besetting ills of human life as well as the frailty of men lead inevitably to tragedy. The great tragic poems and the great tragedies of history may, of course, be read as if they dealt with the exceptional case, but another interpretation is possible. Here writ large in the life of the hero, the great or famous man, is the tragic pattern of human life which is the lot of all men. Sophocles seems to be saying this, when he writes in Oedipus at Colonus: "Not to be born is, past all prizing, best; but, when a man hath seen the light, this is next best by far, that with all speed he should go thither, whence he hath come. For when he hath seen youth go by, with its light follies, what troublous affliction is strange to his lot, what suffering is not therein? - envy, factions, strife, battles, and slaughters; and, last of all, age claims him for her ownage, dispraised, infirm, unsociable, unfriended, with whom all woe of woe abides." Death is sometimes regarded as the symbol of tragic frustration. Sometimes it is not death, but the fear of death which overshadows life, so that for Montaigne, learning how to face death well seems indispensable to living well. "The very felicity of life itself," he writes, "which depends upon the tranquility and contentment of a well-descended spirit, and the resolution and assurance of a well-ordered soul, ought never to be attributed to any man till he has first been seen to play the last, and, doubtless, the hardest act of his part. There may be disguise and dissimulation in all the rest ... but, in this scene of death, there is no more counterfeiting: we must speak out plain and discover what there is of good and clean in the bottom of the pot." So, too, for Lucretius, what happiness men can have depends on their being rid of the fear of death through knowing the causes of things. But neither death nor the fear of death may be the crucial flaw. It may be the temporal character of life itself. It is said that happiness consists in the possession of all good things. It is said that happiness is the quality of a whole life, not the feeling of satisfaction for a moment. If this is so, then Solon's remark to Croesus can be given another meaning, namely, that happiness is not something actually enjoyed by a man at any moment of his life. Man can come to possess all good things only in the succession of his days, not simultaneously; and so happiness is never actually achieved but is always in the process of being achieved. When that process is completed, the man is dead, his life is done. It may still be true that to live well or virtuously - with the help of fortune - is to live happily, but so long as life goes on, happiness is pursued rather than enjoyed. On earth and in time, man does not seem able to come to rest in any final satisfaction, with all his desires quieted at once and forever by that vision of perfection which would deserve Faust's "Stay, thou art so fair!" AS ALREADY INTIMATED, the problem of human happiness takes on another dimension when it is treated by the Christian theologians. Any happiness which men can have on earth and in time is, according to Augustine, "rather the solace of our misery than the positive enjoyment of felicity." "Our very righteousness," he goes on to say, "though true in so far as it has respect to the true good, is yet in this life of such a kind that it consists rather in the remission of sins than in the perfecting of virtues ... . For as reason, though subjected to God, is yet 'pressed down by the corruptible body,' so long as it is in this mortal condition, it has not perfect authority over vice ... . For though it exercises authority, the vices do not submit without a struggle. For however well one maintains the conflict, and however thoroughly he has subdued these enemies, there steals in some evil thing, which, if it do not find ready expression in act, slips out by the lips, or insinuates itself into the thought; and therefore his peace is not full so long as he is at war with his vices." Accepting the definition of happiness as the possession of all good things and the satisfaction of all desires, the theologians compare the successive accumulation of finite goods with the unchanging enjoyment of an infinite good. All endless prolongation of the days of our mortal life would not increase the chances of becoming perfectly happy, because time and change permit no rest, no finality. Earthly happiness is therefore intrinsically imperfect. Perfect happiness belongs to eternal life of the immortal soul, completely at rest in the beatific vision, for in the vision of God the soul is united to the infinite good by knowledge and love. In the divine presence and glory all natural desires of the human spirit are simultaneously satisfied - the intellect's search for truth and the will's yearning for the good. "That final peace to which all our righteousness has reference, and for the sake of which it is maintained," Augustine describes as "the felicity of a life that is done with bondage" - to vice or comfort, to time and change. In contrast, the best human life on earth is miserable with frustrations and an ennui that human nature cannot escape. The doctrine of immortality is obviously presupposed in the theological consideration of happiness. For Kant immortality is a necessary condition of the sout's infinite progress toward the moral perfection, the holiness, which alone deserves perfect happiness. But for theologians like Augustine and Aquinas, neither change nor progress play any part in immortal life. On the contrary, the immortal soul finds its salvation in eternal rest. The difference between motion and rest, between time and eternity, belongs to the very essence of the theologian's distinction between imperfect happiness on earth and perfect happiness hereafter. These matters, of relevance to the theory of happiness, are discussed in the chapters on ETERNITY and IMMORTALITY; and in the chapter on SIN we find another religious dogma, that of original sin, which has an obvious bearing on earthly happiness as well as on eternal salvation. Fallen human nature, according to Christian teaching, is incompetent to achieve even the natural end of imperfect temporal happiness without God's help. Milton expounds this doctrine of indispensable grace in Paradise Lost, in words which God the Father addresses to His Son: Man shall not quite be lost, but sav'd who will, God's grace is needed for men to lead a good life on earth as well as for eternal blessedness. On earth, man's efforts to be virtuous require the reinforcement of supernatural gifts - faith, hope, and charity, and the infused moral virtues. The beatific vision in Heaven totally exceeds the natural powers of the soul and comes with the gift of added supernatural light. It seems, in short, that there is no purely natural happiness according to the strict tenets of Christian doctrine. Aquinas employs the conception of eternal beatitude not only to measure the imperfection of earthly life, but also to insist that temporal happiness is happiness at all only to the extent that it is a remote participation of true and perfect happiness. It cannot be said of temporal happiness that it "excludes every evil and fulfills every desire. In this life every evil cannot be excluded - For this present life is subject to many unavoidable evils: to ignorance on the part of the intellect; to inordinate affection on the part of the appetite-; and to many penalties on the part of the body ... . Likewise," Aquinas continues, "neither can the desire for good be satiated in this life. For man naturally desires the good which he has to be abiding . Now the goods of the present life pass away since life itself passes away ... . Wherefore it is impossible to have true happiness in this life." If perfect happiness consists in "the vision of the Divine Essence, which men cannot obtain in this life," then, according to Aquinas, only the earthly life which somehow partakes of God has a measure of happiness in it. Earthly happiness, imperfect because of its temporal and bodily conditions, consists in a life devoted to God - a kind of inchoate participation here and now of the beatific vision hereafter. On earth there can be only a beginning "in respect of that operation whereby man is united to God. ... In the present life, in as far as we fall short of the unity and continuity of that operation, so do we fall short of perfect happiness. Nevertheless it is a participation of happiness; and so much the greater, as the operation can be more continuous and more one. Consequently the active life which is busy with many things, has less of happiness than the contemplative life, which is busied with one thing, i.e., the contemplation of truth." When the theologians consider the modes of life on earth in terms of the fundamental distinction between the secular and the religious, or the active and the contemplative, they seem to admit the possibility of imperfect happiness in either mode. In either, a devout Christian dedicates every act to the glory of God, and through such dedication embraces the divine in the passing moments of his earthly pilgrimage.

|

||

|

|