|

Word Gems

exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

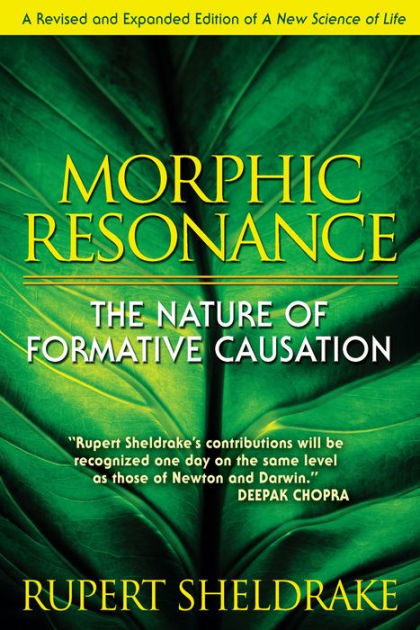

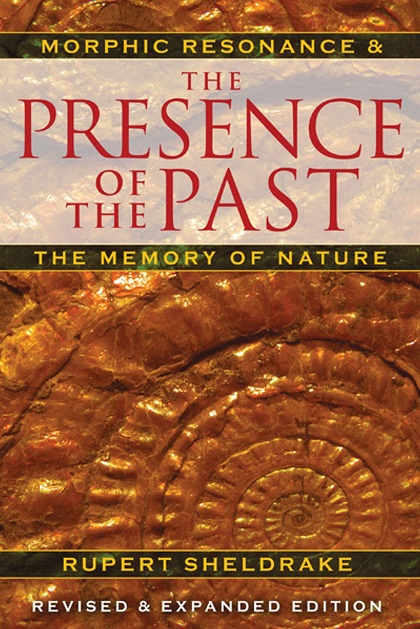

Dr. Rupert Sheldrake's

Theory of Morphogenesis:

A Survey of the Evidence

for Morphic Resonance

return to "Evolution Controversy" contents page

The following represents a survey of main points of evidence for morphic resonance offered by Dr. Sheldrake in various books and lectures.

|

#1: the rats in the water-maze experiment

Editor’s note: The “water-maze experiment” will be found in many of Dr. Sheldrake’s books and lectures, but the following particular discussion is from "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

The theory predicts that if you train rats to learn a new trick in one place, like London, rats all over the world should learn the same more quickly because rats here have learned it.

There’s a kind of collective memory. And when I first thought of this, I said, if this is true, people should have noticed this [because] they’re training rats all the time to learn new tricks.

I looked in the “rat literature” [laughter] and in fact this was already observed in a fascinating series of experiments started by William McDougal at Harvard in the 1920s.

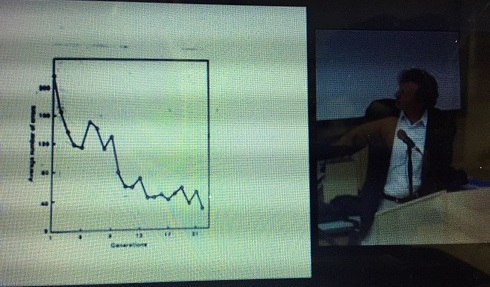

Rats were trained to escape from a water maze, by swimming to an exit; if they swam to the wrong exit, they got an electric shock – one of those old-style [experiments], no one would do that today – anyway, he did it then, and what he found was that the first generation of rats made hundreds of errors before they learned. He bred from them, and the second generation made fewer errors. The third made fewer still, and so on.

And he thought he’d shown the “inheritance of acquired characteristics.” Those of you who’ve studied biology will know that this is the ultimate heresy in [modern] biology. You’re not supposed to have an inheritance of acquired characteristics: what the parents do is not supposed to affect the offspring, because it’s all supposed to be coded in the genes which are passed on, unchanged.

We’ve seen from the fruit-flies [below] that’s not true. The changing development of the parents did affect the offspring and, indeed, all other fies of that breed. What was happening with McDougal’s rats, he thought it was genetic. It was very, very controversial, and his critics said, Oh, well, it was just a flaw in your experiment. You’re breeding these rats and, obviously, you’re taking the ones that learn quickest, [using them] as the parents of the next generation, and you’re unconsciously ignoring the stupid ones that take a long time to learn, so it’s just ordinary “genetic selection.”

Everyone seemed pleased by that [explanation], it was conventional, but McDougal came back and said, Ok, I’ll test that theory. In every generation I’ll take as the parents of the next generation the most stupid rats, the slowest learners. “Genetic selection” should mean they’ll make more and more errors as time goes on.

This is what happened. The number of errors fell, generation by generation…

… from over 200 to start with, down to about 30. And this was with stupid rats.

The [trajectory] should have been going up [the opposite direction]. In fact, they were getting better and better, as time went on. What was happening? “Genetic selection” couldn’t explain this.

People were outraged [laughter]. People tried to repeat his experiments at two universities, in Scotland and Australia. They started off with similar rats, and when they started training their rats in the same [water-maze] apparatus, [these new rats] started where the Harvard rats had left off [laughter] [in terms of quickness to learn].

The ones in Scotland got better and better [surpassing the Harvard rats], learning faster and faster. And then people said, Well, there must be something wrong. And then those in Australia said, Ok, you haven’t included ‘control rats.’ In every generation we’ll test not only those descended from trained parents but rats from a standard line, the same breed, whose parents have never been exposed to these water mazes.

What they found was, both lots got better and better. And this proved it wasn’t genetic. It had nothing to do with modifying genes.

So, everyone heaved a sigh of relief and said, Ok, this refutes Lamarckian Inheritance, it has nothing to do with modifying genes, and the whole episode was closed, and these data were left gathering dust in the archives.

But nobody explained the effect itself. The effect itself fits perfectly with morphic resonance.

Editor’s note: Many years ago, before I’d heard of Dr. Sheldrake’s morphic resonance, I came across something called “the hundredth monkey” principle. In brief, the idea was this: If a monkey, let’s say, on some remote island, learns some new trick or task, for example, a better way of getting at a coconut’s milk, then, slowly, the knowledge of this advancement would spread through the local monkey population. However, by the time the “hundredth monkey” had joined the party, the new skill would generally be known, not just on the remote island, but, everywhere in the world, monkeys would commonly be opening coconuts in the more efficient way. Well, at the time, it did sound a little fanciful to me. Later, checking a little further, I came across an opinion within certain quarters of the scientific establishment which essentially viewed “the hundredth monkey” principle as fairy tale. I conceded that, with the first report, I’d been a victim of fake news. However, as it’s turned out, “the hundredth monkey” principle is based on solid empirical evidence. Rats that learn a new trick in one part of the world affect the learning ability of rats all over the globe. Those who decry and spurn “the hundredth monkey” principle also blind themselves to the “rat literature” evidence, spanning nearly 100 years.

|

#2: the fruit-fly experiment

Editor’s note: The “fruit-fly" experiment” will be found in many of Dr. Sheldrake’s books and lectures, but the following particular discussion is from "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

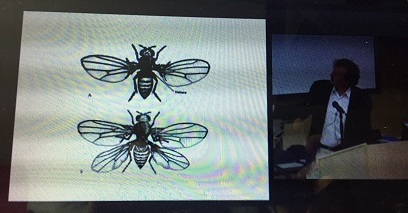

This is a normal fruit-fly [top figure]…

And this [lower figure] is a mutant fruit-fly where the balancing organs, the halteres, have been transformed into an extra pair of wings. These flies with four wings are a bit like the ancestors of flies, dragonflies, which had four wings. So, the fruit-fly, by changes in genes, it’s as if they flipped the channel, and these developing structures develop into wings not halters.

It’s like flipping a channel on your tv set, they affect a switch. But you can produce the same effect, for reasons no one understands, by changing the environment of fruit-flies. If you expose three-hour old eggs of fruit-flies to fumes of ether --I mean, diethyl-ether, the anesthetic – some of the flies develop with four wings instead of two. This is a developmental abnormality, a bit like thalidomide causing human abnormalities, without genetic change, it just disturbs development.

Now, it was discovered by Waddington, the man who put forward the “creode” idea, that if you keep doing this, generation after generation, more and more flies develop abnormally. He thought at first that it was the “genetic selection” effect.

Editor's note: "Genetic selection" is the process by which certain traits become more prevalent in a species than other traits. It describes the forces that determine the traits seen in a population or species.

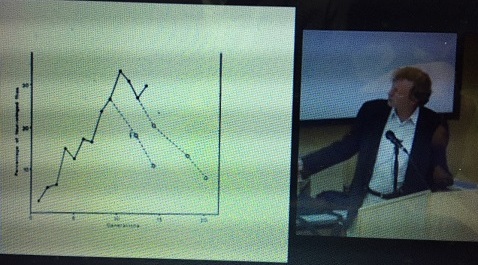

The experiment was repeated at the Open University by Dr. Mae-Wan Ho and her colleagues, and over a series of generations, with an inbred strain where you could have no “genetic selection” effect, they looked at the proportions [of the occurrence of abnormalities].

[On the graph, “generations” along the bottom horizontal line, “percentage with four wings” along the vertical, left, line] First generation about 2% [with four wings], next generation about 7%, until they got up to about 35%. And, in some cases, they stopped exposing the eggs to ether, but still, at a declining rate, they went on forming four-winged flies.

The interesting point from my point of view is this:

After they’d done this [for ten generations], they got some fresh flies of the same strain and exposed them to ether. The first generation were transformed to 10%, the second generation to 20%; compared to 2% and [7%], the first time around.

[What happened was] after all these [earlier-generation] flies had developed abnormally, it became easier for other flies to show the same abnormal form of development. And I would say that was because of morphic resonance. It had nothing to do with genes [because] there was no genetic connection between the new batch of flies and the ones that had been treated previously.

|

#3: crystals become easier to create

Editor’s note: The “crystal experiment” will be found in many of Dr. Sheldrake’s books and lectures, but the following particular discussion is from "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

So, this collective memory is a key feature of all of Nature. The whole of Nature is really a matter of habit. And I see the so-called Laws of Nature as more like habits.

Well, I think, in fact, whether we like it or not, that’s a view that everybody’s going to have to consider sooner or later. Old-style science was built on the idea that the “laws” of Nature were completely fixed. They used to think that Nature is eternal, the laws of Nature are eternal, matter and energy are eternal, and it’s just a matter of things repeating in endless cycles, and so forth. But evolution tells us something completely different. The laws of Nature can’t be eternal, the universe is not eternal. So, the laws of Nature are not eternal, and if the whole universe is evolving, at least the laws have to evolve, but better than “law” is the idea of habit. So, I’m suggesting the “laws” of Nature are more like habits. The morphic fields have a kind of inherent memory.

So, everything has this kind of memory, even crystals. What this means is that if you make a new kind of crystal that’s never existed before, there won’t be a morphic field for that crystal form – you have to wait for one to come into being. But if you keep crystallizing the same thing, over and over again, making crystals all over the world, it’ll get easier and easier to crystallize.

Things will form more readily. This is known to happen in the case of crystals. They get easier to crystallize the more often they’re made.

Chemists usually explain this by saying, fragments of previous crystals travel around the world on the clothing or beards of migrant chemists [laugher of audience] and infect crystallization dishes in other laboratories; or, if there haven’t been any migrant chemists, they move around as invisible dust particles in the atmosphere.

But what I’m saying is that this would happen even if the dust particles are filtered out and if migrant chemists are rigorously excluded [laughter]. Things will get easier to crystallize because of morphic resonance.

Now, I think this happens at all levels, not just in crystals, it happens in biological form. Whenever a habit builds up, it means that things are influenced by all the previous systems. The more there are, the greater the number of influences. There’s a cumulative memory. All the previous systems are slightly different. So, it’s a kind of probability structure… These fields include the memory of everything that’s happened before of that kind. It’s a kind of collective memory.

|

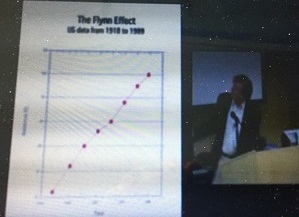

#4: the unwarrantedly improving IQ test scores

Editor’s note: The “IQ" experiment” will be found in many of Dr. Sheldrake’s books and lectures, but the following particular discussion is from "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

It should be getting easier and easier to learn computer-programming, wind-surfing, and every other sport and skill.

Actually, it does seem that people are getting better at learning these things, but it could be better educational videos, improved technologies, seeing it on tv – there’re lots of factors that affect this. To study this you need standardized testing where the same test is done over and over again.

In the 1980s I realized that one perfect source for this would be IQ tests, which have been done in much the same way over many, many years. Morphic resonance would predict that people are getting better at doing IQ tests, not because they’re getting more intelligent, but the tests should be getting easier, because so many people have done them.

I couldn’t get hold of the data to test this, but luckily a New Zealand scientist, James Flynn, took up exactly this question and found that just this sort of thing was happening.

This chart shows the average rise in test scores from 1918 to 1989. As you see there’s been a dramatic and puzzling rise in IQ test scores.

This has happened in Britain, Germany, Japan – in fact, everywhere people have looked they’ve seen this same rising-IQ score effect. This is now called “The Flynn Effect” after James Flynn.

What is the explanation? There’s been tremendous controversy… Better nutrition? Urbanization? People being used to taking tests at school. Television making people smarter – well, no, some say it makes them dumber. None of these things worked out in explaining it, or very much of it.

But it’s exactly what you’d expect on the basis of morphic resonance.

|

#5: songbirds stealing cream phenomenon

Editor’s note: The following information can be found in Dr. Sheldrake’s youtube interview with Joe Rogan at 14:30.

There was a famous case in England with songbirds called “Blue Tits” – in America you call them “Chickadees.”

In the 1920s, these birds started raiding milk bottles [delivered to peoples’ door in the morning]… There were cardboard tops on these bottles. And someone noticed, in Southhampton, that the cream had disappeared, the top had been torn off and the cream was gone. And so they watched and every morning these Blue Tits had figured out that they could tear off this cardboard top and get free cream. And everyone was sort of interested in this.

Then, it turned up many, many miles away, in another part of Britain, and then it turned up somewhere else. Now, Blue Tits don’t fly very far, they’re home-loving birds, they don’t migrate, and so scientists got interested, and they set up a network all over Britain to observe this, and they got reports – it was coordinated from Cambridge University.

And they mapped the spread of the habit, and it became clear that it was spreading faster and faster, and it was independently invented in other parts of Britain. So much so that the professor of biology at Oxford, Sir Allister Hardy, suggested that it must be spreading by a kind of telepathy, that it was spreading too quickly.

The most interesting records are from Holland, where it started happening, as well. During the War, Holland was occupied by the Germans and milk deliveries stopped, and didn’t start again until about 1948, seven or eight years after they stopped.

Blue Tits only live three or four years so there would have been no Blue Tits after the War which would have remembered the “Golden Age Of Free Cream.” And so when milk deliveries began again in Holland, the Blue Tits began drinking cream straightaway, all over Holland.

So, I would say that this is a kind of collective memory that’s spread by morphic resonance and remembered by morphic resonance.

|

#6: mice inheriting the fears of parents

Editor’s note: The following information can be found in Dr. Sheldrake’s youtube interview with Joe Rogan at 17:35.

This was published in Nature, with the provocative title, “Inheriting The Fears Of Fathers.” A very, very, fascinating study…

They used a synthetic chemical… that smells sort of vaguely fruity, something that mice would never encounter in nature, because it’s a synthetic chemical. And they took male mice and exposed them to [the chemical] and [at the same time] gave them a mild electric shock… The result is classical Pavlovian conditioning, a few times of that and as soon as they smelled [the chemical] they were terrified.

Perfectly standard stuff in science. But what wasn’t standard was they then bred from these mice… using artificial insemination, so the mothers never even met the fathers of the next generation.

And then they tested the children and the grandchildren and whenever [these new generations] smelled [the chemical] they were just paralyzed with fear. So, they inherited this fear of the chemical in a single generation! – in a way that regular science simply can’t explain.

And this went far beyond anyone would have expected. There’s evidence from the details of the experiment such that there were some changes in the sperm, some changes in the genes or the epigenetics, which is the “packaging” of the genes, but no one can conceive of how a mouse learned to avoid this smell and being frightened by it, no one knows how that information could be transferred into the genes and the sperm, and so I think that at least part of the explanation of this is morphic resonance – if you make some animals averse to this, their descendents – and other animals of the same kind – will be frightened of it.

|

Editor's note: There are many other examples of morphic resonance which you’ll want to read about on your own. For example, experiments relating to the rat-poison industry, lures that attract bass fish, and one that Rupert did with day-old chicks, very similar to #6, above.

|

Dr. Sheldrake talks about the latest evidence for morphic resonance at a science conference:

|

Whose memories are they? Does the transfer of memory equal a transfer of the entire person?

Dr. Rupert Sheldrake, Consciousness Conference, Barcelona 2025

"... the cases of the reincarnation type, I think what they prove is there's a transfer of memory, as to whether the transfer of memory equals a transfer of the entire person or not, is a big question. Buddhists and Hindus have been debating this from different points of view for millenia. So, I think this opens up a whole new area of discussion ... because I think there are many anomalous-looking cases from the point of view of standard science which might make sense in the light of memory transfer by morphic resonance."

READ MORE

|

|