|

Word Gems

self-knowledge, authentic living, full humanity, continual awakening

Dr. Rupert Sheldrake's

Theory of Morphogenesis:

A Survey of the Evidence

for Morphic Fields

return to "Evolution Controversy" contents page

The following represents a survey of main points of evidence for morphic fields offered by Dr. Sheldrake in various books and lectures.

|

#1: the early stages of a bat and a worm

Editor’s note: The following particular discussion is from Rupert's lecture "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

Now, when we come to embryos – this is an embryo of a bat – all of this develops from a fertilized egg, which has very little structure to start with. How do all these limbs, these structures, come into being? What tells the cells what to do? The answer, within biology now, a very mainstream answer, is the morphogenetic fields of the bat. That’s what shapes it, there’s a kind of invisible shaping blueprint.

Here you see a series of stages in the development in the nematode worm [commonly known as “roundworm”; “nematode” from the Greek, meaning “thread”; an elongated cylindrical worm parasitic in animals or plants], a humble worm with only a few thousand cells. It starts with an egg cell that divides in two, and then you see it going through a series of stages, until this consists of many, many, many different cells with all different structures within it.

These fields that shape developing organisms are different, each organism has its own kind of field, and one reason why biologists liked, and still like, the idea of morphogenetic fields is because fields are intrinsically holistic.

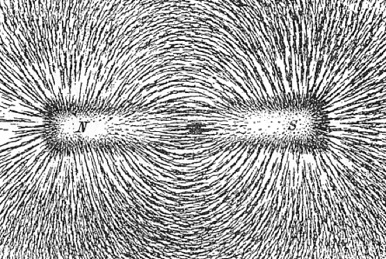

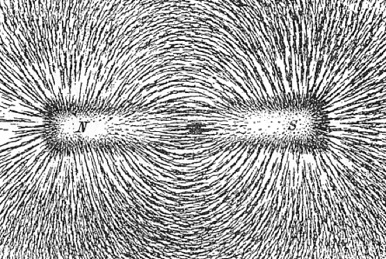

You can’t take a slice out of the Earth’s gravitational field, you can’t take a slice out of a magnetic field. If you try to cut the north pole off a magnet, you don’t get an isolated north pole, you end up with two magnets, each with a complete magnetic field. Now, this is the very nature of fields, they’re holistic, they interconnect, they give form, structure, pattern, and connect things together in a whole.

If you cut magnets into little pieces, you get lots of little magnets, each with a complete field. Now, that’s totally different from the way machines work. Machines are made of parts, put together artificially … that work together, but [the machine] doesn’t have an overall organizing field that makes it a whole. If you cut a machine, a computer, up into pieces, all you get is a broken computer.

So, field phenomena are very different. And living organisms are much more like field phenomena than like machines. If you cut up a machine, you just get a broken machine, but if you cut up or damage an embryo, that’s not what happens. [An embryo might regenerate itself because the morphogenetic field remains intact.] ...

|

#2: the dragonfly embryo

Editor’s note: The following discussion is from Rupert's lecture "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

Here you see a normal dragonfly embryo inside the dragonfly egg. In this one [on the right], the back half was tied off and this part was killed. The back half, in a normal case, [would be lost to the embryo, but] in fact, [the lower portion develops] a complete, but small, embryo within it.

So, by damaging [the upper half], [because the lower half] has a complete morphogenetic field, like half a magnet [exhibiting] a complete magnetic field, it leads to a normal embryo developing. No machine would do that.

|

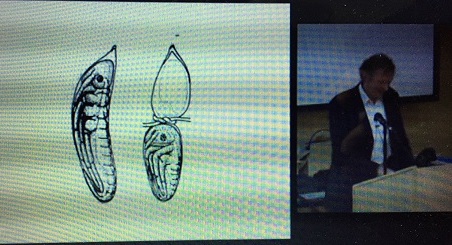

#3: willow trees and flatworms regenerate

Editor’s note: The following discussion is from Rupert's lecture "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

We see the same thing with regeneration. If you cut a plant up into little bits, each cutting can become a whole new plant. Willow trees are particularly good at forming cuttings, and you can make thousands of cuttings from a willow tree.

This [above slide] is a flatworm, cut up into three bits, here [the top figure on the chart], each of the bits can regenerate: the tail bit regenerates a new middle part and head; the middle part gets a new head and tail; [the head part gets a new lower section]. If you cut it cross-wise [the middle figure on the chart], you get a new worm.

And if you cut it in half, from top to bottom [the lower figure on the chart], it generates a new half. Each of these fragments has “the field” of the complete worm associated with it, just like a fragment of a magnet has a complete field, which leads to this regenerative, healing process.

|

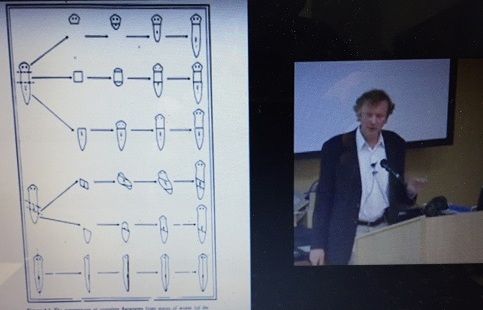

#4: the limbs of a newt regenerate

Editor’s note: The following discussion is from Rupert's lecture "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

These are limbs of a newt, and in this case the newt’s arm was amputated at this point here [top, left side of the chart] , and on this side [top, right side of the chart] it was amputated much further down.

In both cases, the stump regenerates a whole new limb. And, again, this is best understood in terms of the field associated with the limb, even though the limb has been cut off.

Now, we [humans] have much less regenerative capacity than a newt; if you cut off a person’s arm, it doesn’t regenerate. We do have [this ability to] regenerate for many of our tissues – the skin, the intestinal lining, the liver – we do have considerable regenerative powers, without them we wouldn’t heal after damage – but, less than a newt.

However, I think that even human beings after losing limbs still have “the field” of the missing limb, and that’s what underlies the “phantom limb” phenomenon.

People with “phantom limbs” are feeling the field of their missing limb, it’s where the limb should be, and that’s where “the phantom” is experienced. People can move around their phantom limbs. One of my experiments at the moment is trying to detect phantom limbs, the field of the limb. You can read about that in my book, “Seven Experiments That Could Change The World.” It’s a very good, very simple, experiment that any of you involved in subtle healing might like to consider trying it. It costs nothing, and it’s fun to do.

|

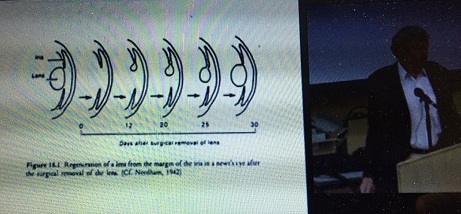

#5: the eye-lens of a newt regenerates; and this, in an unusual way

Editor’s note: The following discussion is from Rupert's lecture "The Biology Of Transformation: The Field," which might be viewed on youtube.

Here’s a form of regeneration that’s even more remarkable. This was done deliberately in the laboratory with the eye of a newt.

The lens was surgically removed… producing a form of damage that would never normally happen in nature.

What happens is that the edge of the iris forms a new lens and regenerates a perfectly functional eye. Now, in the embryonic development of a newt the lens does not form from the edge of the iris, it forms from a folding-in of skin from the outside.

So, it formed a lens from a completely new way, from a different tissue than where it would normally arise from, showing that, there seems to be, a plan of the complete eye, that, if you take away the lens, that plan is still there, and it enables the regeneration process to occur.

|

#6: symmetry and internal resonance: the inexplicable likeness within a snowflake

Editor’s note: The following is from Dr. Sheldrake's book, "The Presence of the Past."

"[One] difficulty arises in trying to understand the way the crystal grows as a whole. Somehow, as molecules in solution come close to the growing surface of the crystal, they 'snap' into place in the growing aggregate. But the way they do this [is unknown]... [The problem is] crystals as a whole show patterns of symmetry that cannot possibly arise from a sum of local effects [i.e., 'local' in the sense of forces acting upon different sections of the growing crystal].

"Consider snowflakes. These crystals generally have a six-fold symmetry, but each snowflake is unique [that is, a product of quantum probability; just as all leaves of a tree are similar yet each is one-of-a-kind]. Within a snowflake, the intricate structure of the six arms is very similar, and these arms themselves are symmetrical. Although the differences among snowflakes can be explained in terms of random variations, the symmetrical development within each snowflake cannot be explained in this way. As John Maddox [put it]:

This must be the consequence of some co-operative phenomenon as a whole. What can that be? What can tell one growing face of a crystal ... what the shape of the opposite face is like? ...

"From the point of view of the hypothesis of formative causation, the lattice structure is organized by a lattice morphic field..."

Editor’s note: Allow me to summarize the incalculable odds of all this occurring by chance. Let’s keep in mind that all snowflakes are unique structures. How many have there been since the dawn of time? As many as the atoms in the universe? Consider the “lego” construction of one snowflake with “molecules snapping into place.” One of the six corners of a snowflake begins to fashion an arm. It will be a unique snowflake arm, never seen before in the history of universe. So far so good. But have a look at the other five arms taking shape across the way. They appear to be cut from the same mold as the first! How could this happen? Did the first little snowflake arm send out a signal with a “blueprint” message? Did the other five peer over the shoulder of the first and play copy-cat? Something else is directing this mirror-imaging. As John Maddox asserted: There “must be … some co-operative phenomenon as a whole” in play here, some sort of teamwork. But I think Dr. Sheldrake has the better understanding. The molecules of the crystals are “snapping into place” based on invisible shape-forming fields, just as iron filings “snap into place” circumscribing the poles of a magnet.

The phenomenon of internal symmetry is not confined to snowflakes. As we open our eyes to this marvel, we will find it everywhere in nature.

“This raises a very general point about the morphogenesis of symmetrical structures: their symmetry seems to require some kind of resonant communication between the symmetrical parts.

“Consider, for example, your right and left hands. They are different from everyone else’s both in the pattern of lines on the palms and the pattern of ridges on the fingertips. Yet they are very similar to each other, just as the arms of the individual snowflake are similar to each other.

“This suggests that within the developing organism, morphic resonance takes place between similar structures, in this case, between the fields of the embryonic hands. This applies to other symmetrical structures, such as the right and left sides of the face; again, although they are not exactly the same, they are very similar, and their development must have been correlated by some kind of resonant phenomenon.

Editor's note: Symmetrical structures of nature are the "same" because of the "blueprint" power of morphic fields, but they're also "different" because of quantum probablism. This is what Dr. Sheldrake meant when he said, "Morphic fields impose order on probablistic systems."

“We may conclude that, in general, within developing organisms, there is an internal resonance between the fields of symmetrical structures and that this self-resonance is essential to their symmetry.

“Because symmetry is such an important feature of natural forms at every level of complexity, an internal resonance between symmetrical structures within the same organism is likely to be an important general feature of formative causation through morphic fields.”

Editor’s note: Morphic fields hold the “blueprint” of what a shape should be. Morphic resonance is a kind of communication among morphic fields bringing them into oneness. For example, morphic fields determine the shape of a snowflake’s arm but morphic resonance brings the fields of all six arms into harmony, one with another.

|

#7: morphic fields and morphic resonance operate not only “between spatially symmetrical structures” within an organism (e.g., right and left hands) - one kind of self-resonance - but also operate across time, influenced by an organism’s own past, which is another kind of self-resonance

Dr. Sheldrake: “The specificity of morphic resonance depends on the similarity of the patterns of activity that are resonating. The more similar the patterns of activity, the more specific and effective will the resonance be.

“In general, the most specific morphic resonance acting on a given organism will be that from its own past states, because it is more similar to itself in the past, especially in the immediate past, than to any other organism.

“This self-resonance will therefore tend to stabilize and maintain organisms in their own characteristic form, as well as harmonize the development of symmetrical structures within the same organism.

“In living organisms, this self-stabilization of morphic fields may go a long way toward explaining how they are able to maintain their characteristic forms in spite of a continuous turnover of their chemical constituents.”

Editor’s note: This is an extremely important point. It is said that every cell in one’s body is replaced – there are different estimates; let’s say – every dozen years. By the time a person reaches middle-age, this process has cycled through several of these renewals. What is the thread of continuity? Some will invoke a spiritual aspect at this point, but let’s speak of the body only here. If every cell of one’s physical form is replaced many times over the course of one’s life, how is the “blueprint” maintained? When those new cells “snap into place,” like molecules in a snowflake, why do we look the same, more or less, in the makeover? The theory of morphic fields, invisible and enduring “blueprints,” provides an answer consistent with the evidence.

|

#8: morphic fields and animal societies: some termite nests require many worker-lifetimes to complete - what is directing this grand construction, where is the blueprint, spanning generations of insects

Editor's note: The following is from Dr. Sheldrake's book, "The Presence Of The Past."

[Dr. Sheldrake quotes] sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson [concerning a particular, very complex termite society]:

It is all but impossible to conceive how one colony member can oversee more than a minute fraction of the work or envision in its entirety the plan of such a finished product [looming ten feet above the ground]. Some of these nests require many worker lifetimes to complete, and each new addition must somehow be brought into a proper relationship with the previous parts. The existence of such nests [some of which are comprised of millions of insect members] leads inevitably to the conclusion that the workers interact in a very orderly and predictable manner. But how can the workers communicate so effectively over such long periods of time? Also, who has the blueprint of the nest?

As the insects build the nest, they respond to the structure that has already been completed, as if they know what needs doing. For example, in the building of arches, workers first construct columns, and then if another column is being built close by, they bend the column toward the other until the two columns meet [as an arch]. No one knows how they do this. They cannot see the other columns; they are blind. There is no evidence that they run back and forth at the base of the columns measuring the distance. Moreover, as Wilson explains,

It is improbable that in the midst of all the confused scampering, that they can recognize distinct sounds from the column by conduction through the substrate.

… the conventional idea that instinctive abilities are somehow “programmed” or “hard-wired” in the nervous system might lead us to expect that termites that build such complex nests have larger and more complex nervous systems than species that build much simpler nests. If fact, they do not.

The hypothesis of formative causation provides an alternative approach, suggesting that the structure of the nests are organized by morphic fields… These fields are not inside the individual termites; rather, the individual insects are inside the [morphic] social fields.

|

#9: morphic fields and animal societies: a large steel plate divided the construction of a massive termite nest; yet, on each side, workers constructed perfectly matching halves.

Editor's note: The following is from Dr. Sheldrake's book, "The Presence Of The Past."

More than eighty years ago the South African naturalist Eugene Marais [observed termite workers repairing holes that Marais made in their mounds]. The workers started rebuilding from all sides, and the new parts all joined correctly even though workers on different sides of the breach did not come into contact with each other and could not see each other, being blind.

Marais then carried out a simple but remarkable experiment. He took a large steel plate …and drove it right through the center of the breach in such a way that it divided the mound and indeed the entire termitary into two separate parts. This is what he found:

The builders on one side of the breach know nothing of those on the other side. In spite of this the termites build a similar arch or tower on each side of the plate. When eventually you withdraw the plate, the two halves match perfectly after the dividing cut has been repaired. We cannot escape the ultimate conclusion that somewhere there exists a preconceived plan which the termites merely execute.

[Marais comments further:]

Expose the queen and destroy her. Immediately, the whole community ceases work on either side of the plate.

Editor’s note: This may be the most significant of Marais’s observations. How do the termites, in their millions, “immediately” gain knowledge of this termitary disruption? Even if “runners” were sent out to communicate, this would take time. But the instantly made-aware worker, on both sides of the plate, all over the nest, is very much like the instant orchestrations to be found in flocks of birds or schools of fish. These latter two examples are mentioned in Dr. Sheldrake’s book, but will not be individually featured here. However, suffice to say, that there is no “leader” at the head of the flock or school toward which the many others look to for direction. Slow-motion photography has confirmed this. Moreover, the movement of the flock or school is so tightly orchestrated that there would be no time for a bird or fish “looking over his shoulder” to account for the rapid syncing of group-movement. For example, the "expansion" of a frightened school of fish might occur in as little as one-fiftieth of a second! Yet there is no collision. "Not only does each fish know in advance where it will swim if attacked, but it must also know where each of its neighbors will swim."

See Dr. Sheldrake’s book. Morphic fields offer a better explanation of these phenomena than the materialistic view. Termites, birds, and fish, operating in unison -- include here, too, migratory behavior -- remind us of iron filings directed as a singularity by an energy field.

|

|

#10: morphic fields and the "extended mind": an energy field surrounds the brain just as an energy field extends beyond a magnet or a cellphone or the Earth

- Editor's note: The following is from a lecture, "Extended Mind," Dr. Sheldrake gave to Google employees. It can be accessed on youtube.

Dr. Sheldrake posits that there’s another kind of morphic field, an energy field which surrounds and extends well beyond the brain. He said that, in effect, this mind energy is a kind of reaching out by the brain/mind to “touch” its environment. This is the basis of telepathy, he suggests, which has been scientifically verified.

This phenomenon occurs in both humans and animals. He gave a great many examples of how this works, but one of the most significant, I think, related to the training of agents of the British SAS, special forces unit, and the American FBI.

In conversations with those having undergone this training, Dr. Sheldrake reports that these agents are taught not to stare directly at the back of an opponent as the staring itself could trigger a reaction. The one stared at could turn around and one’s “cover could be blown” or, in more dangerous situations, could kill you. Dr. Sheldrake says that these agents assert that this kind of mind-power, the sense of being stared at, is a phenomenon of common knowledge in the these special security forces, and the agents thereof are incredulous that this staring effect has not been carefully investigated.

Dr. Sheldrake explains that this “the sense of being stared at” has not been generally investigated by mainstream science because it’s a taboo subject. Science, in a spirit of censoring cultish dogmatism, closes its eyes to anything that offers evidence of a primacy of consciousness and prefers to view the brain materialistically, simply the puppet of the “upward causation” of subatomic particles. See a full discussion of this taboo-bias on the “Evolution” page.

|

|

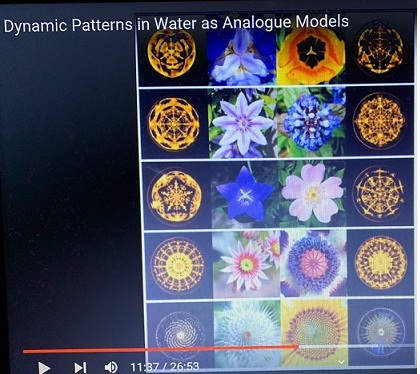

#11: morphic fields and vibratory patterns in water

This item of evidence is most fascinating and can only be touched on in these brief paragraphs. You’ll want to review Dr. Sheldrake’s lecture given in Germany, a conference of the physics, chemistry, and biology of water.

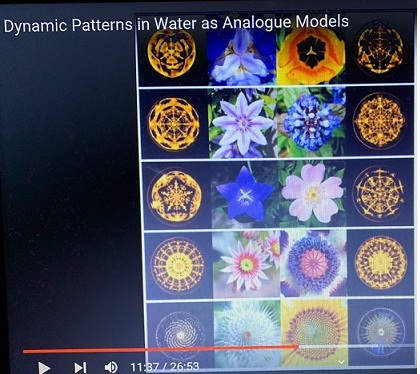

The essential idea here is that vibrating drops of water give rise to different patterns. As the rate of vibration increases, different patterns emerge. The emerging patterns are not haphazard and confused but issue as beautiful geometric-artistic forms.

What's even more significant is that these emerging vibratory patterns begin to resemble forms and shapes that we see in the natural world.

The two outside columns are photographs of the vibratory patterns in water, with the inside columns featuring flowers with similar shapes. In the lecture, Dr. Sheldrake produces many other examples of the vibratory patterns seemingly finding analogue with other aspects of nature; e.g., forms and shapes of pollen and single-celled entities.

What might this mean? Dr. Sheldrake explained that all fields of energy exist in a vibrational state: for example, electromagnetic fields and quantum fields. Therefore, he suggested, that morphogenic fields are also vibrational fields, quantum fields, of activity.

Like the invisible wind revealing itself in the movement of tree branches, the hidden morphogenic fields – which, likely, are electrical wave patterns, he said – will create geometric-artistic patterns in water; which means, vibratory wave patterns might create forms and shapes in the natural world.

|

Dr. Sheldrake: "So, how do these [morphic] fields evolve? Living organisms evolve. Old-style science isn’t really a very evolutionary subject. We now know that the entire cosmos is evolutionary [i.e., the entire universe is evolving]. But how do fields evolve? They can’t just be 'in the genes' because they’re what organize the genes. So, they can’t be inherited genetically. They can’t just be platonic equations, equations somehow beyond time and space, because fields evolve: dinosaurs came into being, they’re now extinct; animals, birds came from dinosaurs, the fields of birds evolved, they weren’t all there at the moment of the Big Bang or even at the origin of life on Earth. How do they evolve and change in Time? They have a kind of history within them. The suggestion I make is that morphic fields have a kind of memory given by a process called morphic resonance. Morphic resonance is the influence of similar patterns of activity on subsequent patterns of activity across space and time. What matters is similarity – doesn’t matter about distance in space and time. Anything that’s happened before, in a self-organizing system, will make it easier for that to happen again. So, there’s a kind of collective memory in every kind of thing. Each species of plant has a kind of collective memory; each species of animal has a kind of collective memory – a memory of form of the way the organism develops, and a memory of behavior, the collective memory of animals are their instincts, their inherited patterns of behavior. And we, of course, have a collective memory, as well, what Jung called the Collective Unconscious."

|

Editor's note: There are other examples of morphic fields in Dr. Sheldrake's books which you’ll want to read about.

|

|