|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

|||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Dr. Iain McGilchrist

return to 'McGilchrist' main-page

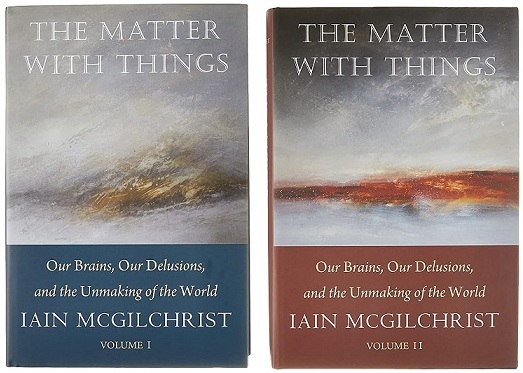

“You can’t make the creative act happen. You have to do certain things, otherwise it won’t happen. But it won’t happen while you are doing them.” “What is required is an attentive response to something real and other than ourselves, of which we have only inklings at first, but which comes more and more into being through our response to it – if we are truly responsive to it. We nurture it into being; or not. In this it has something of the structure of love.” - Iain McGilchrist, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions

“The idea of complementarity is foundational in Nature. So, for example, to turn one’s back on the parts (the workings of the left hemisphere) and accept only the whole (the work of the right hemisphere) is not to ‘get back to wholeness’, because the whole is never an annihilation, but rather a subsumption, of the parts. The true whole exists precisely in this relationship, the tension between parts and an apparent whole.” “. . .depression has repeatedly been shown to be associated with greater realism – provided the depression is not too severe. . . The evidence is that this is not because insight makes you depressed, but because, up to a point, being depressed gives you insight. In understanding one’s role in bringing about a certain outcome, depressives are more ‘in touch’ with reality even than normal subjects. . .” “According to Matthew Fisher, Professor of Physics at the University of California at Santa Barbara, the nuclear spin of phosphate atoms could serve as rudimentary quantum bits (so-called ‘qubits’) of information in the brain, since such phosphate atoms, bonded with calcium in Posner molecules (clusters of nine calcium atoms and six phosphorus atoms), can prevent coherent neural ‘qubits’ from collapsing into decoherence (non-quantum states) for long enough to enable the brain to function somewhat like a quantum computer.” “It is in dealing with death that one is most forcibly made aware of how we yielded, hands down, to the forgetting of Being. One of the few occasions on which at last modern man might be able to grasp the enormity of existence is in the contemplation of death. Yet this is just what we ignore. It is a commonplace that while the Victorians did not talk about sex, they were open about death; we do not talk about death, but are clinically explicit about sex. Unfortunately for us, being open about something robs it of its power, while hiding increases it.” “When our society generally held with religion, we might indeed have committed many of the same wrongs; but power-seeking, selfishness, self-promotion, narcissism and entitlement, neglect of duty, dishonesty, ruthlessness, greed, and lust were never condoned or actively and openly encouraged - even admired - in the way they sometimes are now. In other words, we have lost all shame. And that can't help but make a difference to how we behave.” “Wittgenstein wrote: 'To believe in a God means to understand the question about the meaning of life.' And he continued: 'To believe in a God means to see that the facts of the world are not the end of the matter. To believe in God means to see that the life has a meaning.” “The more focal attention is narrowed, the more it takes its object out of the realm of time, space, the body and emotion.” “Interestingly, much as the happiest people don’t seek happiness, the wealthiest people are not those who most ruthlessly pursue wealth. John Kay cites a number of cases of global giants, household names such as ICI, Boeing, Merck, Pfizer and Citigroup, which were once highly profitable organisations while they focussed on delivering a good product, but which nosedived as soon as the bean-counters took over, and told people to focus on the bottom line – making money. Greed doesn’t pay (although abjuring greed because it pays better to do so is to thwart oneself, since it is the attitude of mind, not a certain action or set of actions, that is both in itself to be desired and goes to create prosperity). Success in business comes, bizarrely enough, as a by-product of running a good business.” “For hundreds of years during the great age of Western science, papers were reviewed by the editor or editors alone. Early attempts at a form of peer review in the nineteenth century already found that referees were soon overwhelmed, that the problem of bias was intractable, and that it had become an obstacle to scientific progress, because it made it almost impossible to say something not already accepted by the establishment. Outside Britain and America it was therefore not widely accepted till relatively recently. Indeed even there: Nature did not establish a formal peer review process until 1967. Of Albert Einstein’s 301 publications there is evidence that only one underwent peer review (in 1932): ‘interestingly, he told the editor of that journal that he would take his study elsewhere!’” “It is arguable that ugliness came into human life only with affluence. In fact, I'd venture to say that there are few artefacts or buildings that we know of prior to 1830 that would be generally considered ugly.” “By paying a certain kind of attention, you can humanise or dehumanise, cherish or strip of all value. By a kind of alienating, fragmenting and focal attention, you can reduce humanity – or art, sex, humour, or religion – to nothing. You can so alienate yourself from a poem that you stop seeing the poem at all, and instead come to see in its place just theories, messages and formal tropes; stop hearing the music and hear only tonalities and harmonic shifts; stop seeing the person and see only mechanisms – all because of the plane of attention. More than that, when such a state of affairs comes about, you are no longer aware that there is a problem at all. For you do not see what it is you cannot see.” “When it is presented with evidence that what it is doing is not working, its invariable response is first to deny that there is a problem, but, if pushed, to respond not that we have done too much of something that is ineffective, but that we simply need to do more of it: because that’s what its theory dictates, and for the left hemisphere theory trumps reality.” “Knowledge of this universe in which we live must be participatory. If you are not prepared to participate, or to take any risks, love will never be part of your life. Risk and vulnerability are of love's essence. And love - as you will know if you have made the experiment and experience it - opens aspects of reality that would otherwise be concealed from you.” “According to Paul Davies, 'the general multiverse explanation is simply naive deism dressed up in scientific language. Both appear to be an infinite unknown, invisible and unknowable system. Both require an infinite amount of information to be discarded just to explain the (finite) universe we live in.” “Mallarmé said that poetry should evoke mystery. So should science and philosophy, if it is true that there are no hard and fast boundaries between the different paths to knowledge, and that the following of all paths to truth leads ultimately to the same place. The wonder of science is not that its clarity reveals how clever we are, but that it reveals, like poetry, a deeper mystery. ‘The more we know’, writes astrophysicist Marcelo Gleiser, ‘the more exposed we are to our ignorance, and the more we know to ask.” “A narrow focus, serial analytic approach encourages us to think that the way to understand music is to see what is in each note, and then add them together to find out the sum. Or to understand flow by looking at a single molecule of water, or even at a small sequence of contiguous molecules of water, and work out from that what flow really is. Two main consequences result from this fallacy of reduction to parts. One is that the search goes in the wrong direction: not upwards, to understand how a phenomenon such as flow functions in the context of everything it takes part in, but downwards, towards units that not only do not exist as discrete entities, but, even if they did, would contain no more of the secret of flow than an agglomeration of single notes explains Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. The other consequence of the atomistic, serial, linear approach is a futile search for what causes what. As an example, a lot of effort has been, and continues to be, directed at disentangling what it is that the right hemisphere is contributing, when we say it is good at understanding metaphor. Is it its affinity for novelty? For complexity? For the implicit? For understanding utterances in context? Or for seeing the connexion between superficially unrelated elements? Which causes what? This is a little like asking what explains the cat’s success in catching mice. Its swiftness? Its agility? Its visual acuity? The sharpness of its claws? Its habit of going out hunting at night? Which is the primary quality? This is the typical left hemisphere approach: if we can only break it up into bits, we will finally understand it, by stringing the bits together in the right order.” “Imagine you are studying the migratory patterns of a certain species of bird. Although we see them soaring and wheeling like free spirits – ‘free as a bird’, we say – they are subtly tethered to the earth. They have freedom to go where they want, it is true, but within certain constraints that are dictated by the realities of their embodied being. To understand a bird’s migratory patterns would require knowing something about the landscapes over which it flies – the opportunities for food and shelter they afford, the weather patterns they give rise to, and so on. These facts would not ‘cause’ the migration, still less are they themselves the migration, nor could they ‘explain it away’: they would simply indicate the constraints on the migration, that helped account for the pattern it tended to take. Sometimes, for contingent, or no discernible, reasons, a bird or birds might vary the pattern considerably and end up in Iceland instead of Scotland. But generally there would be a familiar shape to it, understandable in terms of the whole context: the nature of the land, sea, weather, fauna and flora through and over which the migration route passes.” “Potential is not simply all the things that never happened, a ghostly penumbra around the actual. The actual is the limit case of the potential, which is equally real; the one into which it collapses out of the many, as the particle is the collapse of a quantum field.” “quite match the beginning. And so we have, suddenly, because of this symmetry-breaking ‘mis-step’, something that is mobile, three-dimensional, endlessly generative, while never being wholly predictable (because always moving onward into a new realm of space, not residing always in the old one). It replaces something atemporal, two-dimensional, repetitive, and entirely regular, namely a circle. All the same, viewed down the axis of the spiral it still has the eternally unchanging quality of the circle – particle-like: though viewed from the side it has an oscillatory or vibratory movement, wave-like, changing, progressing and alive. Fractals, though quite different in nature, have this in common with spirals, that they generate difference that is also a kind of sameness.” “we want others to understand the beauty of a landscape with which they may be unfamiliar, an argument is pointless: instead we must take them there and explore it with them, walking on the hills and mountains, pausing as new vantage points continually open around us, allowing our companions to experience it for themselves.”

from the website https://wisewords.blog/book-summaries/the-matter-with-things-volume-1-book-summary/

from https://sobrief.com/books/the-matter-with-things 1. The Brain's Hemispheres Shape Our Understanding of Truth The very brain mechanisms which succeed in simplifying the world so as to subject it to our control militate against a true understanding of it. Two Hemispheres, Two Realities. The human brain, divided into two hemispheres, processes information in fundamentally different ways. The left hemisphere excels at manipulating the world through analysis and control, while the right hemisphere focuses on comprehending the world as a whole and our place within it. This division leads to distinct experiential realities, each with its own strengths and limitations. Left Hemisphere: Control and Manipulation. The left hemisphere simplifies the world, breaking it down into manageable parts for manipulation. This approach is effective for achieving specific goals but can lead to a distorted understanding of the interconnectedness and complexity of reality. It prioritizes power and control, often at the expense of empathy and holistic understanding. Right Hemisphere: Comprehension and Connection. The right hemisphere, on the other hand, seeks to understand the world in its entirety, embracing ambiguity and nuance. It emphasizes relationships, context, and the interconnectedness of all things. This approach fosters a deeper, more truthful understanding of reality but may be less effective for immediate manipulation and control. 2. Attention Determines Our Perceived Reality Attention changes the world. How you attend to it changes what it is you find there. Attention as a Creative Force. Attention is not merely a cognitive function but the very manner in which our consciousness engages with existence. The way we direct our attention shapes the world we experience, bringing certain aspects into focus while obscuring others. This makes attention a moral act with far-reaching consequences. Hemisphere-Specific Attention. The left hemisphere employs narrow, focused attention, ideal for grasping and manipulating specific objects. The right hemisphere utilizes broad, sustained attention, better suited for understanding the larger context and detecting novelty. These distinct attentional styles lead to different perceptions of reality. The Illusion of Objectivity. The left hemisphere often assumes that reality is independent of our observation, a collection of inert things to be manipulated. However, the right hemisphere recognizes that our consciousness plays a role in shaping reality, and that relationships are primary, more foundational than the things related. 3. Perception is an Active, Hemisphere-Dependent Process The explicit is not more fully real than the implicit. It is merely the limit case of the implicit, with much of its vital meaning sheared off: narrowed down and ‘finalised’. Beyond Passive Reception. Perception is not a passive reception of sensory data but an active process of synthesis and interpretation. Our brains constantly fill in gaps, anticipate patterns, and construct a coherent experience of the world based on prior knowledge and expectations. This process is influenced by the attentional styles of the two hemispheres. Left Hemisphere: Detail and Linearity. The left hemisphere focuses on details, explicit information, and linear relationships. It excels at categorization and analysis but may miss the larger context and implicit meanings. This can lead to a literal and decontextualized understanding of the world. Right Hemisphere: Context and Metaphor. The right hemisphere, in contrast, excels at grasping the whole picture, understanding metaphor, and appreciating the interconnectedness of things. It is more attuned to implicit meanings, emotional cues, and the nuances of human experience. This holistic approach provides a richer, more nuanced understanding of reality. 4. Judgment Requires Balancing Logic and Intuition The explicit is not more fully real than the implicit. It is merely the limit case of the implicit, with much of its vital meaning sheared off: narrowed down and ‘finalised’. Beyond Pure Logic. Judgment, the process of evaluating information and forming beliefs, requires a balance of logic and intuition. While logic provides a framework for reasoning and analysis, intuition offers a deeper understanding of context, values, and human experience. Left Hemisphere: Logic and Certainty. The left hemisphere seeks certainty and relies on explicit rules and procedures. It excels at logical deduction but may struggle with ambiguity and nuance. This can lead to rigid and inflexible judgments that fail to account for the complexities of real-world situations. Right Hemisphere: Intuition and Discernment. The right hemisphere, on the other hand, embraces ambiguity and relies on intuition to guide its judgments. It is more attuned to context, emotional cues, and the interconnectedness of things. This holistic approach allows for more nuanced and compassionate judgments. 5. Imagination Unveils a Deeper Reality Potential is not simply all the things that never happened, a ghostly penumbra around the actual. The actual is the limit case of the potential, which is equally real. Beyond the Material World. Imagination, often dismissed as mere fantasy, is essential for understanding the nature of reality. It allows us to transcend the limitations of our immediate experience, explore possibilities, and connect with something deeper and more meaningful. Left Hemisphere: Representation and Abstraction. The left hemisphere tends to see reality as a collection of material things, independent of our observation. It prioritizes representation and abstraction, often at the expense of direct experience. This can lead to a limited and mechanistic view of the world. Right Hemisphere: Presence and Potential. The right hemisphere, in contrast, recognizes the importance of imagination in unveiling the unseen potential of reality. It sees the world as a constantly self-creating process, full of possibilities that are equally real as the actual. This perspective fosters a sense of wonder, purpose, and connection to the cosmos. 6. Science and Philosophy: Complementary Paths to Truth The isolated knowledge obtained by a group of specialists in a narrow field has in itself no value whatsoever, but only in its synthesis with all the rest of knowledge and only inasmuch as it really contributes in this synthesis toward answering the demand, τ?νες δ? ?με?ς; ‘Who are we?’ Bridging the Divide. Science and philosophy, often treated as separate disciplines, are in reality complementary paths to truth. Science provides empirical evidence and mechanistic explanations, while philosophy offers frameworks for understanding the meaning and implications of that evidence. A true understanding of reality requires a synthesis of both. Science's Limitations. Science, with its emphasis on objectivity and reductionism, can only take us so far. It may reveal how the world works but cannot fully explain why it exists or what its purpose is. It is also limited by its reliance on models and representations, which are necessarily simplifications of reality. Philosophy's Role. Philosophy, with its emphasis on intuition, imagination, and ethical considerations, can help us fill in the gaps left by science. It can provide a broader context for understanding the human condition and our place in the cosmos. 7. The Crises of Our Time Demand a Re-Evaluation of Our Worldview At the core of the contemporary world is the reductionist view that we are – nature is – the earth is – ‘nothing but’ a bundle of senseless particles, pointlessly, helplessly, mindlessly, colliding in a predictable fashion, whose existence is purely material, and whose only value is utility. The Dangers of Reductionism. The prevailing reductionist worldview, which reduces everything to senseless particles and prioritizes utility, is actively damaging the natural world and our own well-being. It endangers everything we should value, including morality, spirituality, and the sense of the sacred. A Call for Transformation. We have reached a point where there is an urgent need to transform both how we think of the world and what we make of ourselves. This requires a shift away from the left hemisphere's dominance and a greater appreciation for the wisdom and insights of the right hemisphere. Relevance to Contemporary Crises. The crises the world faces, from environmental destruction to social fragmentation, are rooted in a distorted understanding of reality. By embracing a more holistic and interconnected worldview, we can begin to address these challenges and create a more sustainable and fulfilling future. 8. The Unforeseen Nature of Reality Requires a New Perspective My ultimate aim is to contribute a new perspective from which to look at the fundamental ‘building blocks’, as we think of them, of the cosmos: time, space, depth, motion, matter, consciousness, uniqueness, beauty, goodness, truth, purpose and the very idea of the existence or otherwise of a God. Beyond the Familiar. The prevailing worldview, heavily indebted to reductionism, seriously distorts the evidence of the nature of reality. A new perspective is needed, one that embraces the unforeseen nature of the cosmos and the limitations of our current understanding. Revisiting Fundamental Concepts. This new perspective requires a re-evaluation of the fundamental building blocks of the cosmos, including time, space, matter, consciousness, and purpose. By challenging our cherished assumptions, we can begin to see the world in a richer and more truthful way. A New Vision of the World. The ultimate goal is to contribute a new perspective from which to look at the fundamental building blocks of the cosmos, one that is far-reaching in its scope, and consistent across the realms of contemporary neurology, philosophy and physics. This new vision will encourage us toward very different conclusions about who we are and what our future holds. FAQ Exploration of brain hemispheres: The book investigates how the left and right hemispheres of the brain perceive and interpret reality differently, shaping our understanding of the world, culture, and even science. Critique of modern worldview: McGilchrist critiques the dominance of left-hemisphere thinking in Western society, which leads to fragmentation, reductionism, and a loss of meaning and connection. Interdisciplinary synthesis: Drawing from neuroscience, philosophy, psychology, and cultural history, the book offers a comprehensive account of how brain lateralization influences cognition, creativity, science, and spirituality. Why should I read The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist? Deep understanding of cognition: The book provides nuanced insights into how the divided brain shapes individual thought, creativity, and even societal trends, challenging simplistic left/right brain myths. Relevance to contemporary issues: McGilchrist connects brain lateralization to modern challenges like environmental degradation, social fragmentation, and the crisis of meaning, offering a new lens for understanding these problems. Enrichment of worldview: By integrating scientific findings with philosophical and spiritual traditions, the book encourages readers to reconsider their relationship with truth, reality, and the sacred. What are the key takeaways from The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist? Hemispheric asymmetry matters: The left and right hemispheres process information in fundamentally different ways, with the right focusing on context, wholeness, and meaning, and the left on detail, abstraction, and control. Imbalance has consequences: Overreliance on left-hemisphere modes leads to fragmentation, loss of meaning, and a mechanistic worldview, affecting mental health, creativity, and culture. Integration is essential: A dynamic interplay between hemispheres—where the right’s synthesis and meaning-making complements the left’s precision and analysis—is necessary for a fuller grasp of reality. How does Iain McGilchrist define the differences between the left and right brain hemispheres in The Matter With Things? Right hemisphere: Associated with holistic, contextual, embodied, and intuitive processing, the right hemisphere grasps the bigger picture, relationships, and the living reality of the world. Left hemisphere: Specializes in analytic, abstract, sequential, and detail-focused processing, excelling at language, logic, and manipulation of symbols but often missing context and meaning. Dynamic interplay: McGilchrist emphasizes that both hemispheres are necessary and should work in balance, with the right as the “Master” and the left as the “Emissary.” What is the "hemisphere hypothesis" in The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist? Two incompatible ways of attending: The brain’s hemispheres sustain two different, often incompatible, experiential worlds—right hemisphere attends broadly and comprehensively, left hemisphere attends narrowly and manipulatively. Evolutionary purpose: This division evolved to balance focused exploitation (left) with open vigilance and understanding (right) for survival. Asymmetrical relationship: The right hemisphere is the ‘Master’ that comprehends the world and knows its limits, while the left is the ‘Emissary’ that manipulates but is often overconfident and simplistic. How does The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist explain the role of attention and perception in shaping reality? Attention as creative act: Attention is not just a cognitive function but a moral act that shapes what is brought into being; how we attend changes what we find. Hemispheric differences: The right hemisphere’s attention brings a fuller, more truthful world into being, while the left narrows and fragments reality, sometimes causing parts of the world to ‘cease to exist’ for the subject. Perception as active judgment: Perception is an interpretive process involving both hemispheres, with the right providing holistic context and the left focusing on details and categorization. What does The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist say about creativity, intuition, and imagination? Right hemisphere dominance: Creativity, intuition, and imagination are strongly associated with right hemisphere activity, which enables holistic, metaphorical, and novel connections. Intuition as foundational: Intuition is described as a rapid, holistic, and embodied understanding that precedes analysis and is essential for expertise and scientific discovery. Imagination as reality-shaping: Imagination is not mere fantasy but a creative force that brings reality into being, foundational to science, art, and reason. How does The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist critique reductionism, the machine model, and modern science? Limitations of the machine model: Living organisms are dynamic, context-dependent processes, not static machines; the machine metaphor fails to capture purpose, adaptability, and complexity. Science’s partial view: Science provides powerful but partial accounts of reality, often privileging left-hemisphere abstraction and control while neglecting context, meaning, and the role of metaphor. Need for balance: McGilchrist calls for integrating right-hemisphere perspectives—holism, context, and process—into science to avoid reductionism and better understand life. What is McGilchrist’s view on the nature of truth and knowledge in The Matter With Things? Truth as encounter: Truth is not absolute or fixed but arises from the encounter between us and reality, a creative, reciprocal process akin to a relationship. Limits of rationality: Rationality is linear and rule-based (left hemisphere), while reason is holistic and contextual (right hemisphere); both are needed, but rationality alone cannot capture the fullness of truth. Role of metaphor and ambiguity: Metaphor is foundational to understanding, and ambiguity is necessary for capturing the richness of meaning and lived experience. How does The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist address consciousness, matter, and the mind-matter problem? Consciousness as fundamental: McGilchrist argues that consciousness is ontologically prior and foundational, not merely an emergent property of matter. Brain as permissive, not generative: The brain enables or filters consciousness rather than producing it outright, challenging materialist assumptions. Matter and consciousness intertwined: The book suggests that matter and consciousness are complementary aspects of the same reality, with consciousness possibly being the ground from which matter arises. What does The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist say about purpose, teleology, and values in nature and the cosmos? Purpose as intrinsic: Life and the cosmos exhibit intrinsic purposefulness, not imposed from outside but arising naturally through evolutionary and creative processes. Values as foundational: Truth, goodness, and beauty are not human inventions but intrinsic to the cosmos, disclosed through consciousness and especially via the right hemisphere. Openness and freedom: Purpose is compatible with randomness and indeterminacy, allowing for creativity and free will rather than rigid determinism. What are the best quotes from The Matter With Things by Iain McGilchrist and what do they mean? “The divided brain is not a metaphor but a reality.” This underscores the book’s central thesis that hemispheric differences are fundamental and have real consequences for perception and culture. “The left hemisphere’s way of seeing is a kind of tunnel vision.” McGilchrist critiques the left hemisphere’s narrow focus, highlighting the limitations of purely analytical thinking. “Our world is unmade by the dominance of the left hemisphere.” This statement connects cognitive imbalance to societal and environmental degradation, calling for a rebalancing of hemispheric perspectives. “Reason teaches us that on such and such a road we are sure of not meeting an obstacle; it does not tell us which is the road that leads to the desired end. For this it is necessary to see the end from afar, and the faculty which teaches us to see is intuition.” This quote highlights the importance of intuition and the right hemisphere in discovery and creativity. Review Summary The Matter With Things is hailed as a masterpiece of neuroscience, philosophy, and epistemology. Readers praise McGilchrist's erudition, depth of analysis, and transformative insights into brain hemispheres, consciousness, and reality. Many consider it life-changing and among the most important works of our time. Critics note its length and occasional mysticism. The book challenges materialist worldviews, exploring science, reason, intuition, and metaphysics. While demanding, most reviewers find it deeply rewarding, offering a new perspective on human experience and the nature of reality. Iain McGilchrist is a psychiatrist, philosopher, and neuroscientist renowned for his work on brain hemisphere function and its cultural implications. His previous book, "The Master and His Emissary," explored similar themes. McGilchrist spent over a decade researching and writing "The Matter With Things," drawing on a vast range of sources across science, philosophy, and the arts. He is known for his interdisciplinary approach, combining neuroscience with broader cultural and philosophical insights. McGilchrist's work challenges conventional understanding of brain function and advocates for a more holistic, right-hemisphere-dominant worldview. He is respected for his erudition and ability to synthesize complex ideas across multiple fields.

from https://footnotes2plato.com/2022/10/13/the-matter-with-things-by-iain-mcgilchrist/ “The Matter With Things” by Iain McGilchrist “Questions such as those concerning scientific truth, the nature of reality, and the place of man in the cosmos require for their study some knowledge of the constitution, quality, capacities and limitations of the human mind through which medium all such problems must be handled.” I’ve just finished reading The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World (2021), Iain McGilchrist’s two volume follow-up to The Master and His Emissary (2009). Volume 1 of TMWT focuses on “the ways to truth,” revisiting the hemisphere hypothesis and unpacking the respective roles of the left and right hemispheres in attention, perception, judgment, apprehension, emotion, creativity, science, reason, imagination, and intuition. Volume 2 then explores the implications of the hemisphere hypothesis for what is likely to be true about the universe itself, including deep inquiries into time, motion, space, matter, consciousness, value, and the sacred. I’ll have a chance to discuss the book with Iain this weekend via video conference, an event hosted by my graduate program (CIIS.edu/pcc) which is open to the public (Sunday, Oct. 16 at 11am Pacific; email me for a Zoom link). What follows are some initial thoughts, shared to introduce but also in an effort to think with the ideas laid out in this marvelous book. The Matter With Things presents a comprehensive argument intended both to diagnose and to treat a pathological world view. Neuroscience is relevant not simply for the truths it unveils about how the brain permits and constrains our consciousness, but because of how an understanding of these constraints can help heal what ails us. Modern Westerners are doing grave damage to the world—to ecosystems, to culture, and to ourselves—as a result of a lop-sided way of seeing. McGilchrist has laid out a comprehensive and, in my opinion, thoroughly convincing case that this imbalance can be fruitfully interpreted as the result of a “left hemisphere insurrection” (1325). As he had already argued in The Master and His Emissary, the materialism, egoism, and other sordid pathologies affecting our world can be read as the consequence of the left hemisphere’s usurpation of the right, claiming for itself the starring role when its evolutionarily intended part is that of supporting actor. Readers familiar with Owen Barfield and Rudolf Steiner, or other thinkers of the evolution of consciousness (e.g., Jean Gebser, Sri Aurobindo, William Irwin Thompson, Ken Wilber, …) will find what McGilchrist has to say about the growing dominance of the left hemisphere nicely complements their accounts of the rise of the modern materialistic mode of thought out of the more participatory modes which preceded it. While McGilchrist is trained as a psychiatrist and well-versed in the study of neuropathology, his explication of the disordered brain is decidedly not another example of “Nothing-Buttery” seeking to reduce human consciousness to neuro-chemical mechanisms. Rather, brain pathologies are studied as windows into the enabling powers of consciousness. As Sperry* put it above, and as biochemist Erwin Chargaff reiterates, the wise scientist will be aware of “the eternal predicament that between him and the world there is always the barrier of the human brain” (The Heraclitean Fire, 123). The brain is the barrier between but as such also the physical medium through which consciousness comes into contact with reality. The brain is a medium, mind you, not a cause. Rather than resorting to some kind of neuro-idealism—i.e., the view wherein, as Whitehead quipped “bodies, brains, and nerves [are thought to be] the only real things in an entirely imaginary world” (Science and the Modern World, 91)—McGilchrist emphasizes the extent to which brain lateralization mirrors the dipolar coincidentia oppositorum at the creative core of the cosmos itself. It is not just that the brain organizes our knowledge and experience of the world in this way, but that reality is this way, with the brain reflecting it because, as Whitehead would say, every interrelated part of Nature has a tendency to be in tune. As Plotinus and Goethe knew, the eye sees by becoming sunlike. Just so, the brain thinks truly by conforming with the rhythm of being. “Understanding the structure of the brain and how it functions can help us see the constraints on consciousness, much as, to use another metaphor, the banks of a river constrain its flow and are integral to its being a river at all, without themselves being sufficient to cause the river, or being themselves the river, or explaining it away.” Further, while the right hemisphere is clearly the protagonist of McGilchrist’s story, the solution is not to excise the crucial function of the left. When properly kept in check and attentive to context the left hemisphere offers much that enhances our unique human capacities. “The brain needs two streams of consciousness, one in each hemisphere, but they are like two branches of a stream that divide round an island and then reunite.” In the healthy brain, each act of perception begins with the implicit wholeness of reality being taken up by the right hemisphere; the left hemisphere then goes to work explicating and analyzing, seeking the correct account of things. But unless its accounts are continually complicated and synthesized again by the right hemisphere, the bits of information provided by the left fail to acquire any meaning.** Problems occur when the left hemisphere imagines it can interpret and navigate the world on its own. The brain deficit literature reviewed by McGilchrist makes it clear not only that the left hemisphere on its own is incapable of sustaining a coherent picture of the world-rhythm, what’s worse, it has no idea when it has lost the beat. Patients with right hemisphere damage (thus relying on the left for processing experience) will vehemently deny anything is wrong with them, even when deficits are obvious. Inspired by William James, McGilchrist provides a helpful list of theoretical interpretations of the mind/brain relation (TMWT, 1085) (these are my glosses): “Emission” theory, where neurochemistry is considered to be the fully explanatory cause of consciousness. In such a view, humans are just especially complicated robots designed by a Dawkinsian Blind Watchmaker. For McGilchrist, and I certainly agree, such views are utterly incoherent and self-contradictory, symptoms of possession by an overzealous left hemisphere. “Transmission” theory: the embodied brain is considered to be a passive receiver of a cosmic mind-field. As McGilchrist described it, “It thinks—thought takes place in the field of me.” “Permission” theory: inclusive of transmission but also understands the embodied brain as a creative constraint and purposeful filter actively contributing new value to mind-at-large. If not already obvious, McGilchrist favors this theory. It follows that consciousness is not a thing, nor a brain excretion, but a betweenness, a process of connection permitted by the living activity of our organism. And as Whitehead reminds us, the brain and body are “just as much part of nature as anything else there—a river, or a mountain, or a cloud” (Modes of Thought, 30). Consciousness is not a part accidentally added on to the periphery of the universe when the right number of neurons became aggregated. Consciousness is the inside of the whole world-process. It is amplified by the brain, but not produced inside the head. One of my favorite chapters in TMWT is Ch. 12, “The Science of Life.” McGilchrist does a wonderful job summarizing new paradigm approaches to biology that break free of the incoherence of mechanistic reductionism. There remains “a manifest dissonance at the core of biology today,” as many biologists still insist on equating science with mechanical explanation, despite the fact that physics long ago left simple mechanism behind. McGilchrist makes easy work of Dawkins’ genetic reductionism (i.e., “selfish genes”), revealing the structural similarities between his mechanomorphic imagination and that of natural theologian William Paley. Dawkins, in effect, saves the machine model by reinventing God, putting his eyes out, and calling him by another name. The place of teleology in modern biology is captured well by Haldane’s analogy (cited by McGilchrist): telos is the mistress that biologists cannot be without but are unwilling to be seen with in public (TMWT, 1186). Translating the hemisphere differences into philosophical terminology stemming from the German Idealists, McGilchrist distinguishes Verstand from Vernunft. Kant originally intended to capture the Latin distinction between ratio and intellectus, themselves attempts to render the Greek terms dianoia and nous (both on the supersensible side of Plato’s divided line analogy). There are various ways of translating these terms into English. I’ve tended to render them as “understanding” and “reason,” respectively, but McGilchrist prefers “rationality” and “reason.” The terms we choose are immaterial; the point is that the distinction has been thoroughly discussed by Western philosophers and indeed seems to map precisely onto the hemisphere differences. Rationality is a linear, piecemeal, analytic mode of thought, while reason seeks a more well-rounded, unifying, and organic sense of the world. “I suggest that these two versions reflect the typical mode of operation, and exemplify the characteristics of, the left and right hemispheres, respectively. [Verstand/Rationality] is rigid, aims for certainty, tends to ‘either/or’ thinking, is abstract and generalised, ignores context and aims to free itself from all that is embodied, in order to gain what it conceives to be eternal truths. [Vernunft/Reason] is deeper and richer, more flexible and tentative, more modest, aware of the impossibility of certainty, open to polyvalent meaning, respecting context and embodiment, and holding that while rational processing is important, it needs to be combined with other ways of intelligently understanding the world.” Rationality can (or should) only ever be an intermediate processor, since it cannot ground itself at the perceptual bottom end nor give meaning to its outcome at the conceptual top end; in this sense it is always bookended by intuition and imagination (TMWT 552). Intuition here means an immediate and embodied sense of the Gestalt pattern holding sway at the base of each perceptual event, and Imagination the mysterious power that Kant affirmed was essential for synthesizing general concepts with particular percepts to bring forth meaningful experience. As Wordsworth had it in The Prelude, this highest form of Imagination acts not only cognitively but lovingly, being one and the same as “reason in her most exalted mood.” Though he draws upon countless sages East, West, and Indigenous, McGilchrist expresses a deep allegiance to four philosophers in particular, a German, an American, a Frenchman, and a Brit: Friedrich Schelling, James, Henri Bergson, and Alfred North Whitehead. From Schelling, he inherits a feeling for the Weltseele or World-Soul, the animating spirit of the universe of which each organism is a unique recapitulation emerging like a whirlpool in the river of reality. He quotes a few sentences from the first pages of Schelling’s 1805 Aphorismen über die Naturphilosophie, which are worth sharing in some length since his words capture well the overall thrust of TMWT: “There is no higher revelation, neither in science, religion, nor art, than that of the divinity of the universe: yes, these originate and have meaning only through this revelation. … Where the light of that revelation fades, people seek to understand things not in relation to the universe, as unified, but as separate from one another, just as they seek to understand themselves in isolation and separation from the universe: there you see science become sclerotic and disintegrated, with great effort expended for little growth in knowledge, as grains of sand are counted one by one to build the universe. … Not only is it mere abstraction that separates the sciences from one another, it is also abstraction that separates science itself from religion and art. … Science is knowledge of the laws of the whole, that is, of the universal. But religion is contemplation of the particular in its bond with the universe. Religion consecrates the scientist priest of nature through the devotion with which he cares for what is separated. It guides the drive for the universal along the bounds set by God, and thus mediates science and art as a sacred bond forming the universal and the particular into one.” From James comes McGilchrist’s appreciation for a sense of pure experience originally undivided by the concepts of subject and object. He also upholds the pragmatic maxim that concepts and theories must always be evaluated in terms of their consequences for experience, thus refusing the left hemisphere’s haste in explaining away whatever does not fit into its abstract models. There is no “outside” beyond experience against which science might compare its models, and so ultimately our criteria for truth must be consistent with and adequate to experience, lest we devolve into incoherence by denying the very conditions that make our knowing possible. Below I share my response to a tweet by Richard Dawkins, who you might call the archbishop of scientistic fundamentalism. From Bergson, McGilchrist learned the importance of the distinction between Intelligence and Intuition, which is another way of describing the respective approaches of the hemispheres. Intelligence (or the left hemisphere) ignores the fluidity of the world, petrifying everything living and applying a logic of solid bodies in order to grasp and utilize the world piecemeal for its own purposes. Intuition (right hemisphere), on the other hand, puts us directly in touch with the creative life inherent to temporal flow and organic development. From Whitehead, who like Schelling, James, and Bergson emphasized the reality of concrete becoming over abstract being, McGilchrist draws several lessons. One concerns the care that must be taken when engaging in abstract thought by attending to the importance of a “right adjustment”—a proper measure and manner—in our deployment of abstractions (576). In other words, there are aesthetic criteria that should inform our use of concepts when carving up the world. Whitehead was an especially hemispherically balanced philosopher capable of navigating the heights of logical analysis while never losing touch with the depths of visceral feeling. It is a rare mind indeed who can understand and advance the algebras of Grassman and Hamilton as well as the poetry of Wordsworth and Shelley. Whitehead realized that some degree of abstraction is inescapable, even in our perceptual experience of the world (e.g., each of our five sense organs abstracts a specific channel from the aesthetic continuum of cosmic becoming). Similarly, our concepts cannot help but cut up the complex wholeness of the world, but if we trace the grain of the wood as we do so, we are less likely to do violence to the Real. By never losing sight of the limitations of the models we deploy, we can avoid succumbing to the left hemisphere trap of replacing the territory with a map (Whitehead’s famous fallacy of misplaced concreteness). Whitehead was also unwilling to conceive of value as something invented and added on to the world by our human subjectivity. Rather, like Max Scheler who argued we perceptive value in the world via “value-ception” (Wertnehmung) (TMWT, 1127), Whitehead’s cosmos is pervaded by value-experience, which each act of perception (or “prehension” in his terms) discloses to us. Our experience of value discloses the world’s truth, beauty, goodness, and purpose to us. Our human values are derived from these cosmic values. As McGilchrist puts it, a “web of values [underlies] the meaning of our actions” (TMWT, 1123). Those familiar with Whitehead’s process theology may sense the resonance between McGilchrist’s underlying “web of values” and the primordial nature of God. McGilchrist’s book climaxes in a discussion of the sacred. He admits to some uneasiness about the “God” word, but there really are no suitable replacements. Perhaps “consciousness” in the sense McGilchrist uses it in an attempt to characterize the ground of being comes closest to a contemporary replacement, but even this term is hardly less charged with potentially misleading connotations. Dionysius the Areopagite spoke of “the superessential radiance of divine darkness” (TMWT, 1246), capturing the paradoxical nature of this Being of beings. The challenge with finding the right word is to mark that mystical sense of the “suchness” or “thatness” characterizing our existence without thereby creating an idol. The left hemisphere tends to see words as arbitrary signs, while the right to some extent relates to them as symbols fused with the reality they are meant to indicate (I think of Coleridge’s term to describe the self-contained, non-allegorical meaning of true myth, “tautegorical,” a word which won Schelling’s approval in his late lectures on the subject). McGilchrist quotes Abraham Heschel: “God is the result of what man does with his higher incomprehension,” which functions as a nice reminder that theological discourse is, at best, a left hemisphere way of representing something intuited by the right (TMWT, 1207, 1232). McGilchrist, in this spirit, affirms a panentheistic view of the God-world relationship wherein God is simultaneously in the world, and the world in God. Rather than an omnipotent and so impassive or unmoved mover, McGilchrist follows Whitehead in affirming a vision of God as feeling-with all creation, “a fellow sufferer” who in some sense needs our love to be fulfilled. “The power of God is the worship [God] inspires,” as Whitehead puts it in Religion in the Making. Or in Meister Eckhart’s terms: “We are all meant to be mothers of God, for God is always needing to be born” (TMWT, 1237). McGilchrist wagers that, when it comes to the existence of God, it may be that you must first believe in order to see. In other words, faith may be the prerequisite by which we cultivate the disposition necessary to perceive the divine ground of being. Faith is not a matter of assenting to particular propositions, but an attitude of reverent openness toward reality. As I wrote in my Physics of the World-Soul, and as McGilchrist reiterates (TMWT, 1219), whether in science or in religion “what there is to be known is reciprocally bound up with the way that we attempt to know it” (PWS, 59). … *Incidentally, Roger Sperry, who won a Nobel prize for his split brain research, did his doctoral work at the University of Chicago under the supervision of Paul Weiss. Weiss had studied with Alfred North Whitehead at Harvard in the 1920s. I am not sure whether any or much of Whitehead’s organic philosophy rubbed off on Sperry, but I found this connection notable. ** Those familiar with Whitehead’s account of perception in terms of causal efficacy (or bodily reception), presentational immediacy (or sense perception), and symbolic reference may detect some resonances (follow this link for a short essay explicating Whitehead’s theory of perception in light of Wordsworth’s poetry).

from https://channelmcgilchrist.com/insights-from-the-matter-with-things/

The LH treats the world like a predator would; it locks onto something to chase it down and kill it. The primary tool we now use to manipulate the world is language, so that’s where it dominates. The left hemisphere has a much more extensive vocabulary than the right, and more subtle and complex syntax. It extends vastly our power to map the world and to explore the complexities of the causal relationships between things. This is surely its raison d’être, and it is valuable to a predator, at least in simple circumstances, where there are not many factors, as there almost always are once one starts taking the broader view. Like a child pulling the wings off a butterfly, the LH reduces things down to ingredients, so as to understand them and manipulate them, but it often kills what it touches. A joke isn’t funny when it’s explained. The world loses its magic when reduced to atoms. But most critically, mechanistic analysis of lines on spreadsheets fails to account for the way the whole system flows together. As I’ve written ad nauseam, this is a massive failing of reductionism and our analytical approach to inherently complex systems. In a formulation which is staggeringly consistent throughout the book, the ideal is a Right => Left => Right transition. McGilchrist talks about the need for real world experience to originate in the right hemisphere, to be moved to the left for processing, but then returned to the right for synthesis into its global context. The musician hears a piece of beautiful music, deconstructs it into notes and learns it painstakingly, then eventually performs it intuitively. Problems emerge when we fail to do the essential final stage of putting the pieces back together. The critical imbalance: The central idea of McGilchrist’s work is that of an imbalance between the hemispheres: the left should be the servant of the right, but it is now too often the master. McGilchrist illustrates why this is radically problematic. The LH has access to infinitely less information, yet tends to lie when faced with its own limitations. Some LH stroke victims get the right side of their body knocked offline, and they are aware of the paralysis in their right arm. But if their RH gets knocked out, the remaining left hemisphere will categorically deny anything is wrong with their right side: They will deny completely that they have a paralyzed arm and if forced to move it, they will say “there, I just moved it,” while nothing moved. And if you bring the hand round in front of them and say “no, move that” they say, “Oh, that’s not my arm that belongs to that man in the next bed” …. the left hemisphere has a very high opinion of itself, and the right hemisphere has a much more modest opinion of itself, which goes hand-in-hand with the fact that the right hemisphere is more intelligent, not just emotionally and socially more intelligent, but more cognitively intelligent than the left hemisphere. The left hemisphere is more competitive, but also less able to admit when it’s wrong.+ “It should be stressed that the right-hemisphere [deficit] patients virtually never respond ‘I don’t know’ to an open-ended question. Instead, they generally contrive an answer – confabulating if necessary – in seeming indifference to the inappropriateness of the response.” – Penelope Myers. “In my opinion, it is the most stunning result from split-brain research … The right hemisphere does not do this. It is totally truthful.” – Michael Gazzaniga A central problem is that the RH is comparatively mute. The LH, as its goal is power and control over the world, has greater usage of language, linearity, and logic. It is great at “grasping” things, breaking them down and working out how to use them, but it consistently misses the importance of the whole. Just because something is logical, consistent. and articulately expressed doesn’t make it true. What does the hemisphere hypothesis tell us about thinking better? It’s pretty nuanced, but McGilchrist’s general take is easily anticipated: we have overemphasized reductive reasoning at the significant cost of intuition. I have read many, many books on how to use the LH to be more rational, use mental models, reduce cognitive biases, etc., but have seen relatively few on how to use the RH. The idea is to better see what lies beyond reason. Pascal, one of the greatest philosopher-mathematicians that ever lived, nonetheless said that ‘the ultimate achievement of reason is to recognize that there is an infinity of things which surpass it. It is indeed feeble if it can’t get as far as understanding that.’ In The Master and his Emissary, McGilchrist talks about using reason to achieve a still higher “suprarationality” where it transcends its own limitations. Music is one such example: One might make a distinction between what is irrational (against reason) and what is ‘suprarational’ (beyond reason). Music might act as an everyday example of something very real, possessed of deep meaning, and not irrational, but suprarational. A sensitivity for the implicit, music, creativity, and the ability to recombine parts to see the whole is the specialty of the RH. Throughout Part 2, McGilchrist persuasively argues that: The right hemisphere is responsible for, in every case, the more important part of our ability to come to an understanding of the world, whether that be via intuition and imagination, or, no less, via science and reason. Again, there’s a necessary tension, but with the RH having overarching control and ideally the final say. The right can incorporate insights from the left, but the left can’t see what the right sees. Again- it’s Right/Left/Right in process: “Reason alone will not serve. Intuition alone can be improved by reason, but reason alone without intuition can easily lead the wrong way. They both are necessary. The way I like to put it is that when I have an intuition about something, I send it over to the reason department. Then after I’ve checked it out in the reason department, I send it back to the intuition department to make sure that it’s still all right.” – Jonas Salk As both sides can do a little of everything, it’s not only the LH that uses science and reason. But, as the two hemispheres do the same things in different ways, there’s a practical application to knowing when to use each side. Where the circumstances are familiar, the problem is determinate and explicit, the situation is congruent with one’s belief bias, and the presentation is lexical, there is a clear left hemisphere advantage in reasoning. But where the circumstances are unfamiliar, indeterminate or implicit, challenge one’s bias, or are not expressed in primarily lexical terms – or require interpretation in the light of context – there will be a critical role for the right hemisphere. Impact on civilization: It originally seemed implausible to me that an “internal” imbalance in our brains could influence and reflect our “external” world. Now I see it literally everywhere I look. I clearly observe limited LH thought in myself and in people around me, as well as the way our modern world is shaped and treated. Cultures across time have myths that warn about the dangers of exactly the hemispheric imbalance we are currently experiencing. In both ancient Greece and Rome, it heralded the collapse of their civilizations. John Glubb’s theory of civilizations found that they last on average two hundred and fifty years, and the “age of intellect” typically arrives just before a collapse. The period of most separation and disengagement from our environment also makes us the most fragile. McGilchrist thinks we’re now at urgent risk of it happening again. McGilchrist is particularly taken with an ancient Iroquois myth, but a familiar contemporary example is Disney’s The Lion King. The overtly intellectual brother Scar overthrows the king Mufasa, and the result is the deterioration of the entire environment; Pride Rock becomes a barren wasteland. Perhaps most worryingly, McGilchrist draws a very convincing parallel between modern society and the symptoms of autism and schizophrenia. Both of which seem to be relatively recent conditions, emerging post industrialization. Excessive abstraction has been described as ‘probably at the source of cognitive deficit in schizophrenia’ – living in the map, not the world: words that refer only to other words; abstractions that become more real than actualities; symbols that usurp the power of what they symbolise: the triumph of theory over embodied experience. I believe there are resonances here with academic trends in the humanities, with scientism, and even with the world-picture of the average Western citizen. This observation seems to have a lot of common-sense evidence going for it. It’s curiously reflected in the structure of the world we inhabit. Modernity is filled with grids and straight lines, features totally absent in nature. We exist separated from our immediate environment, with our lives increasingly mediated by screens and digital abstractions. Everything we value; intimacy, friendship, community is now provided in digital form, but with all the nourishment removed. We are already living in a simulation. Our focus is on safety, power, and control, yet we’ve never felt so disconnected. If the LH could invent a world, it would surely look a lot like this. Why is any of this important to us as individuals? Carl Jung believed personal transition back from “ego” (LH) to “self” (RH) was the meaning of life. Yet again we see the Right/Left/Right formulation: we go from naïve children in the flow, to powerful but disconnected adults, ideally back to the flow again. But this time with an increased appreciation for the whole. The “hero’s journey” that is the dominant story of almost every human culture alludes to this transition as the path to individual and societal renewal. Neuroanatomist Jill Bolte Taylor suffered arguably the world’s most famous left-hemisphere stroke. Her original viral TED talk describes the bliss and oneness she experienced as her left-hemisphere was knocked offline. She explicitly agrees with the hero’s journey parallel in her recent book Whole Brained Living: In the language of the brain, the hero must step out of his own ego-based left-brain consciousness into the realm of his right brain’s unconsciousness. At this point the hero feels connected to all that is, and is enveloped by a sense of deep inner peace. The link between the individual and society is slightly clearer in this context; correcting the imbalance is our brains restores our harmonious relationship with the flow of life. In fact, as the book unfolds, McGilchrist makes a surprisingly persuasive case that the RH is in relationship with values, truth, reality, life, flow, and everything of ultimate value. But, perhaps even more usefully, allows you to identify the kind of LH thinking that hinders you from directly experiencing it. All that matters most to us can be understood only by the indirect path: music, art, humour, poems, love, metaphors, myths, and religious meaning, are all nullified by the attempt to make them explicit. McGilchrist relates this back to what the Navajo called “seeing with soft eyes.” The analogy I always think of is one of those “magic eye” pictures where you could only see the whole image by relaxing your eyes. Then when you re-focused it would disappear again. The somewhat practical personal takeaway for me is the importance of subtle attention. If narrow LH attention sees and knows little, lies, and doesn’t even know what it doesn’t know, we certainly shouldn’t be using it to direct our lives. Instead we need to use the RH for our exploratory growth. Thus you’re left with the paradox what we can’t pursue anything we love too directly. Instead let go of the tiller and follow our bliss. That way we have a chance of participating in the flow of unfolding that the RH is directly in relationship with. I recently outlined a quick rundown of this concept in the opening minutes of my last podcast with Jim O’Shaughnessy. Finally- eight ideas that stood out. Again, this isn’t a summary, just some resonant ideas and illustrations. Anger. This is one of the most strongly lateralised of all emotions, and it lateralises to the LH. “What is striking is that anger, irritability, and disgust stand out as the exceptions to right hemisphere dominance, fairly dependably lateralising to the left hemisphere.” Hence whenever I get angry, or see others getting angry, I almost invariably notice it’s a reaction to a threat to the individual ego. It is now a staggeringly useful tool for self-knowledge. Paradox. Often a paradox is a way of directly illustrating the tension between the two ways our brains view the world. As I tried to articulate in The Ship of Theseus, the idea is that seeing only the parts can blind you to a common sense appreciation of the whole. The dangers of following scientific orthodoxy. Well into the 1980s, human infants were operated on without anaesthetic. The scientific consensus was that they couldn’t feel pain because they couldn’t verbalize it. “Their screams were just the creakings of a machine.” We might be committing the same atrocity with other species due to a related flawed logic. Embodiment: As you may have read in my recent piece, embodiment seems like a critical missing piece for the rediscovery of our connection. It will not be surprising that it’s a RH trait. “It is widely accepted in clinical neurology that the right hemisphere is specialised for perception of the body… A meta-analysis shows that it is the right hemisphere that predominates in receiving and interpreting information from the heart.” The book closes with a story related by a member of the Swiss Parliament Lukas Fierz: Jung told us about his encounter with a Pueblo chief whose name was ‘Mountain Lake.’ This chief told him, that the white man was doomed. When asked why, the chief took both hands before his eyes and – Jung imitating the gesture – moved the outstretched index fingers convergingly towards one point before him, saying ‘because the white man looks at only one point, excluding all other aspects’. Later in life, Fierz met a successful industrialist, self-made billionaire and significant adversary of his Green Party movement in Switzerland. I asked him what in his view was the reason for his incredible entrepreneurial and political success. He took both hands before his eyes and moved the outstretched index fingers convergingly towards one point before him, saying ‘because I am able to concentrate on only one point, excluding all other aspects’. I remember that I had to swallow hard two or three times, so as not to say anything … In McGilchrist’s own words, he wrote the book because he wants to take people to a place where they see a different viewpoint that is new, but not alien. He often hears that readers intuitively know that his perspective is true, but haven’t had it articulated to us in this way before. That has been my experience. Tom Postscript: some personal views on how to read the book. Adele made Spotify remove the shuffle button from her new album to make sure it was listened to in the order she intended. I’m broadly in agreement with that view when it comes to really important books. But, I also appreciate not everyone has the time or inclination to read a book of this length. McGilchrist himself suggests it can be dipped in and out of. If you’ve already read The Master and his Emissary, you can get by reading the summaries of the chapters in Part 1. This section is a pretty challenging read. My personal take on Part 1 is that he’s probably spent so long defending his thesis that every five pages there’s a staggering insight, and 4 pages of studies and proof. This makes it dangerous to skim. I would recommend you read the final chapter of Part 1 on the relationship between schizophrenia and autism and the character of the modern world. For the remainder, I wouldn’t skip a single page of Parts 2 and 3. The intimidating length of the book obviously makes me sad that a great number of people will be deterred from reading it. Especially as he says it’s so long because he wanted it to be comprehensible to anyone with a relatively basic understanding of the vast breadth of deep concepts he covers.