|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

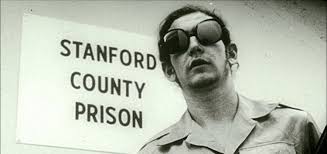

The Stanford Prison Experiment

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN YOU PUT GOOD PEOPLE IN AN EVIL PLACE? DOES HUMANITY WIN OVER EVIL, OR DOES EVIL TRIUMPH? THESE ARE SOME OF THE QUESTIONS WE POSED IN THIS DRAMATIC SIMULATION OF PRISON LIFE CONDUCTED IN 1971 AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY. "How we went about testing these questions and what we found may astound you. Our planned two-week investigation into the psychology of prison life had to be ended after only six days because of what the situation was doing to the college students who participated. In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress. Please read the story of what happened and what it tells us about the nature of human nature." Professor Philip G. Zimbardo

Stanford Prison Experiment by Saul McLeod published 2008, updated 2016 Aim: To investigate how readily people would conform to the roles of guard and prisoner in a role-playing exercise that simulated prison life. Zimbardo (1973) was interested in finding out whether the brutality reported among guards in American prisons was due to the sadistic personalities of the guards (i.e. dispositional) or had more to do with the prison environment (i.e. situational). For example, prisoner and guards may have personalities which make conflict inevitable, with prisoners lacking respect for law and order and guards being domineering and aggressive. Alternatively, prisoners and guards may behave in a hostile manner due to the rigid power structure of the social environment in prisons. If the prisoners and guards behaved in a non-aggressive manner this would support the dispositional hypothesis, or if they behave the same way as people do in real prisons this would support the situational explanation. Procedure: To study the roles people play in prison situations, Zimbardo converted a basement of the Stanford University psychology building into a mock prison. He advertised for students to play the roles of prisoners and guards for a fortnight. More than 70 applicants answered the ad and were given diagnostic interviews and personality tests to eliminate candidates with psychological problems, medical disabilities, or a history of crime or drug abuse. The study comprised 24 male college students (chosen from 75 volunteers) who were paid $15 per day to take part in the experiment. Participants were randomly assigned to either the role of prisoner or guard in a simulated prison environment. There were 2 reserves and one dropped out, finally leaving 10 prisoners and 11 guards. The guards worked in sets of 3 (being replaced after an 8 hour shift), and the prisoners were housed 3 to a room. There was also a solitary confinement cell for prisoners who 'misbehaved'. The prison simulation was kept as “real life” as possible. Prisoners were treated like every other criminal, being arrested at their own homes, without warning, and taken to the local police station. They were fingerprinted, photographed and ‘booked’. Then they were blindfolded and driven to the psychology department of Stanford University, where Zimbardo had had the basement set out as a prison, with barred doors and windows, bare walls and small cells. Here the deindividuation process began. When the prisoners arrived at the prison they were stripped naked, deloused, had all their personal possessions removed and locked away, and were given prison clothes and bedding. They were issued a uniform, and referred to by their number only. The use of ID numbers was a way to make prisoners feel anonymous. Each prisoner had to be called only by his ID number and could only refer to himself and the other prisoners by number. Their clothes comprised a smock with their number written on it, but no underclothes. They also had a tight nylon cap to cover their hair, and a locked chain around one ankle. All guards were dressed in identical uniforms of khaki, and they carried a whistle around their neck and a billy club borrowed from the police. Guards also wore special sunglasses, to make eye contact with prisoners impossible. Three guards worked shifts of eight hours each (the other guards remained on call). Guards were instructed to do whatever they thought was necessary to maintain law and order in the prison and to command the respect of the prisoners. No physical violence was permitted. Zimbardo observed the behavior of the prisoners and guards (as a researcher), and also acted as a prison warden. Findings: Within a very short time both guards and prisoners were settling into their new roles, with the guards adopting theirs quickly and easily. Within hours of beginning the experiment some guards began to harass prisoners. They behaved in a brutal and sadistic manner, apparently enjoying it. Other guards joined in, and other prisoners were also tormented. The prisoners were taunted with insults and petty orders, they were given pointless and boring tasks to accomplish, and they were generally dehumanized. Push-ups were a common form of physical punishment imposed by the guards. The prisoners soon adopted prisoner-like behavior too. They talked about prison issues a great deal of the time. They ‘told tales’ on each other to the guards. They started taking the prison rules very seriously, as though they were there for the prisoners’ benefit and infringement would spell disaster for all of them. Some even began siding with the guards against prisoners who did not obey the rules. Over the next few days the relationships between the guards and the prisoners changed, with a change in one leading to a change in the other. Remember that the guards were firmly in control and the prisoners were totally dependent on them. As the prisoners became more dependent, the guards became more derisive towards them. They held the prisoners in contempt and let the prisoners know it. As the guards’ contempt for them grew, the prisoners became more submissive. As the prisoners became more submissive, the guards became more aggressive and assertive. They demanded ever greater obedience from the prisoners. The prisoners were dependent on the guards for everything so tried to find ways to please the guards, such as telling tales on fellow prisoners. During the second day of the experiment the prisoners removed their stocking caps, ripped off their numbers, and barricaded themselves inside the cells by putting their beds against the door. The guards retaliated by using a fire extinguisher which shot a stream of skin-chilling carbon dioxide, and they forced the prisoners away from the doors. Next, the guards broke into each cell, stripped the prisoners naked and took the beds out. The ringleaders of the prisoner rebellion were placed into solitary confinement. After this the guards generally began to harass and intimidate the prisoners. Prisoner#8612 had to be released after 36 hours because of uncontrollable bursts of screaming, crying and anger. His thinking became disorganized and he appeared to be entering the early stages of a deep depression. Within the next few days three others also had to leave after showing signs of emotional disorder that could have had lasting consequences. (These were people who had been pronounced stable and normal a short while before). Zimbardo (1973) had intended that the experiment should run for a fortnight, but on the sixth day it was terminated. Christina Maslach, a recent Stanford Ph.D. brought in to conduct interviews with the guards and prisoners, strongly objected when she saw the prisoners being abused by the guards. Filled with outrage, she said, "It's terrible what you are doing to these boys!" Out of 50 or more outsiders who had seen our prison, she was the only one who ever questioned its morality. Zimbardo (2008) later noted, “It wasn't until much later that I realized how far into my prison role I was at that point -- that I was thinking like a prison superintendent rather than a research psychologist“. Conclusion: People will readily conform to the social roles they are expected to play, especially if the roles are as strongly stereotyped as those of the prison guards. The “prison” environment was an important factor in creating the guards’ brutal behavior (none of the participants who acted as guards showed sadistic tendencies before the study). Therefore, the findings support the situational explanation of behavior rather than the dispositional one. Zimbardo proposed that two processes can explain the prisoner's 'final submission'. Deindividuation may explain the behaviour of the participants; especially the guards. This is a state when you become so immersed in the norms of the group that you lose your sense of identity and personal responsibility. The guards may have been so sadistic because they did not feel what happened was down to them personally – it was a group norm. The also may have lost their sense of personal identity because of the uniform they wore. Also, learned helplessness could explain the prisoners submission to the guards. The prisoners learnt that whatever they did had little effect on what happened to them. In the mock prison the unpredictable decisions of the guards led the prisoners to give up responding. After the prison experiment was terminated Zimbardo interviewed the participants. Here’s an excerpt: ‘Most of the participants said they had felt involved and committed. The research had felt "real" to them. One guard said, "I was surprised at myself. I made them call each other names and clean the toilets out with their bare hands. I practically considered the prisoners cattle and I kept thinking I had to watch out for them in case they tried something." Another guard said "Acting authoritatively can be fun. Power can be a great pleasure." And another: "... during the inspection I went to Cell Two to mess up a bed which a prisoner had just made and he grabbed me, screaming that he had just made it and that he was not going to let me mess it up. He grabbed me by the throat and although he was laughing I was pretty scared. I lashed out with my stick and hit him on the chin although not very hard, and when I freed myself I became angry."’ Most of the guards found it difficult to believe that they had behaved in the brutalizing ways that they had. Many said they hadn’t known this side of them existed or that they were capable of such things. The prisoners, too, couldn’t believe that they had responded in the submissive, cowering, dependent way they had. Several claimed to be assertive types normally. When asked about the guards, they described the usual three stereotypes that can be found in any prison: some guards were good, some were tough but fair, and some were cruel. Critical Evaluation: Demand characteristics could explain the findings of the study. Most of the guards later claimed they were simply acting. Because the guards and prisoners were playing a role their behaviour may not be influenced by the same factors which affect behavior in real life. This means the study's findings cannot be reasonably generalized to real life, such as prison settings. I.e the study has low ecological validity. However, there is considerable evidence that the participants did react to the situation as though it was real. For example 90% of the prisoners’ private conversations, which were monitored by the researchers, were on the prison conditions, and only 10% of the time were their conversations about life outside of the prison. The guards, too, rarely exchanged personal information during their relaxation breaks - they either talked about ‘problem prisoners’, other prison topics, or did not talk at all. The guards were always on time and even worked overtime for no extra pay. When the prisoners were introduced to a priest, they referred to themselves by their prison number, rather than their first name. Some even asked him to get a lawyer to help get them out. The study may also lack population validity as the sample comprised US male students. The study's findings cannot be applied to female prisons or those from other countries. For example, America is an individualist culture (were people are generally less conforming) and the results may be different in collectivist cultures (such as Asian countries). A strength of the study is that it has altered the way US prisons are run. For example, juveniles accused of federal crimes are no longer housed before trial with adult prisoners (due to the risk of violence against them). Another strength of the study is that the harmful treatment of participant led to the formal recognition of ethical guidelines by the American Psychological Association. Studies must now undergo an extensive review by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) before they are implemented. A review of research plans by a panel is required by most institutions such as universities, hospitals and government agencies. These boards review whether the potential benefits of the research are justifiable in the light of possible risk of physical or psychological harm. These boards may request researchers make changes to the study's design or procedure, or in extreme cases deny approval of the study altogether. Ethical Issues: The study has received many ethical criticisms, including lack of fully informed consent by participants as Zimbardo himself did not know what would happen in the experiment (it was unpredictable). Also, the prisoners did not consent to being 'arrested' at home. The prisoners were not told partly because final approval from the police wasn’t given until minutes before the participants decided to participate, and partly because the researchers wanted the arrests to come as a surprise. However this was a breach of the ethics of Zimbardo’s own contract that all of the participants had signed. Also, participants playing the role of prisoners were not protected from psychological harm, experiencing incidents of humiliation and distress. For example, one prisoner had to be released after 36 hours because of uncontrollable bursts of screaming, crying and anger. However, in Zimbardo's defence the emotional distress experienced by the prisoners could not have been predicted from the outset. Approval for the study was given from the Office of Naval Research, the Psychology Department and the University Committee of Human Experimentation. This Committee also did not anticipate the prisoners’ extreme reactions that were to follow. Alternative methodologies were looked at which would cause less distress to the participants but at the same time give the desired information, but nothing suitable could be found. Extensive group and individual debriefing sessions were held and all participants returned post-experimental questionnaires several weeks, then several months later, then at yearly intervals. Zimbardo concluded there were no lasting negative effects. Zimbardo also strongly argues that the benefits gained about our understanding of human behaviour and how we can improve society should out balance the distress caused by the study. However it has been suggested that the US Navy was not so much interested in making prisons more human and were in fact more interested in using the study to train people in the armed services to cope with the stresses of captivity.

|

||

|

|