|

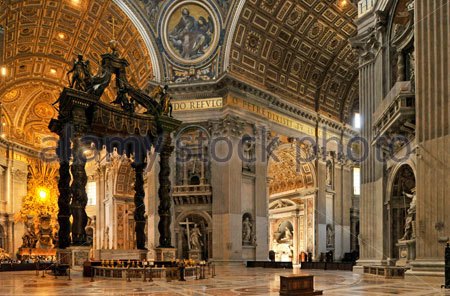

British historian Kenneth Clark's Civilisation is a survey of history by reviewing its art. In chapter seven he examines the “visual exuberance” of sixteenth century Papal Rome, “the most grandiose piece of town planning ever attempted.”

What happened? How did this imperialistic, swooningly sensuous art and architecture come to be?

The Protestant heretics of Northern Europe had called into question Rome’s authority. However, instead of negotiating with and meeting the dissidents half-way, the Church doubled down on its absolutist ways, a response history calls the Counter-Reformation.

In effect, the Church’s position became: “You say that we’ve lost the early spirit of Christianity, our humble beginnings, with too much emphasis on materialism? Well then, we’ll show you materialism, with a degree of ornateness and extravagance, never before seen in history. In this way, we'll reassert our power and authority in the world.”

“Everything” in Bernini’s Papal Rome, says Clark, “is calculated to overwhelm” and intimidate.

The disagreeing scholars in the North had “most forcibly” and “most logically” disemboweled certain key Catholic doctrines, but the Church would now attempt to recapture lost territory not by “intellectual means” but via the exhibitionistic Baroque which “appealed” to the fearful “through the emotions.”

art as flight from reality and repression

The Great Church had taken a severe shellacking from the Northern heretics, in that, it would never again regain it former status in the world. Refusing to acknowledge its diminished estate, however, it would escape “from reality” of lost empire “into a world of illusion” via super-ostentatious art.

Once this propaganda policy had been set in motion, the artwork of Papal Rome gathered to itself a momentum of meretriciousness; now, feeding on itself, “there was nothing it could do except become more and more sensational.”

illusion and exploitation

Illusion, judges Clark, was matched by a swelling “exploitation.” Vice of this sort was not unknown in pre-Reformation days, but now “never on so vast a scale.” The gigantic mansions of Rome’s elite, financed by the Church’s impoverished, “were simply expressions of private greed and vanity.”

Dr. Clark, in a mental sweep of history, concludes chapter seven with a philosophical note. He muses that this “sense of grandeur” is part of a “human instinct”; however, “carried too far, it becomes inhuman. I wonder if a single thought that has helped forward the human spirit has ever been conceived or written down in an enormous room...”

Editor's note: See my book featuring the benefits of sitting quietly in a small room.

Would Jesus say there's something wrong with this picture?

See Bill Maher's interview with Latin scholar Father Reginald Foster at the Vatican.

|

Maher: Does all of this opulence "look like anything, like anything, Jesus Christ had in mind? When you look at a giant palace like that, does it seem at odds with the message of the Founder?”

Foster: “Well, certainly. That’s obvious.”

|

|