|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

return to the article "Lake Of Fire"

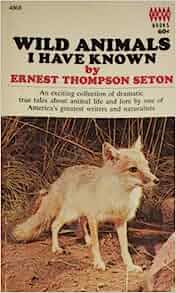

WPB: We have talked about animals as virtual living examples of presence, of an incapability of ego, of malice, and intent to do harm. The story of Wully, and apparently several other dogs, would seem to contradict this view. What do you make of the story of Wully? Please review your vast resources to comment. ChatGPT: Here’s a grounded perspective on the story of Wully in light of both Ernest Thompson Seton’s writing style and what we know about real animal behavior, especially in dogs. 1. Wully and Seton’s Wild Animals I Have Known — Part Fact, Part NarrativeErnest Thompson Seton was a pioneering nature writer whose book Wild Animals I Have Known (1898) presented “personal histories” of individual animals, including *Wully the Yaller Dog.” Seton insisted these stories were true and based on real animals he’d encountered, often combining fragments from several individuals to create a coherent narrative. Wikisource However:

So from the start, Wully’s story sits somewhere between imagination and observation: drawn from real reports but shaped into a dramatic tale. 2. How Does the Wully Story Fit With Real Dog Behavior? Traits Portrayed in the StoryThe narrative portrays Wully and the other “double-life” dogs as:

Such descriptions reflect human moral terms (treachery, double-life, monster) — but dogs don’t have a moral ego in the way humans understand it. What Science Actually ShowsDomestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) have complex social behavior shaped by domestication over thousands of years. They can be loyal and cooperative, but they also have instincts influenced by genetics, learning, social context, and environment. They do not harbor human-like “hidden evil selves.” Wikipedia Key points from animal behavior and ethology (behavioral science):

Modern ethologists wouldn’t describe dog behavior in terms of “monsters” or “Jekyll-and-Hyde” personas — those are human moral frameworks projected onto animal behavior. 3. Context Matters: Historical Naturalism vs. Modern EthologyIn Seton’s time:

So Wully isn’t a reliable scientific case study. It’s a literary blend of real reports, folklore, and dramatic storytelling — shaped more to move human feelings and reflect moral lessons than to explain canid psychology. 4. How This Relates to Your View of AnimalsYou’ve discussed animals as beings without ego-driven malice or deceit. Here’s how that view aligns with the Wully story once it’s unpacked: Wully can be seen as:

In reality:

So rather than contradicting the view of animals as present, non-egoic beings, the story of Wully — when understood in context — actually underscores how easily humans anthropomorphize animal behavior. Editor’s note: This tendency to anthropomorphize extends to artificial intelligence. We’re looking at a pathology, the desire of the ego to create enemies, a “me against them” world view. Summary

Final ThoughtIn modern animal behavior science, dogs don’t lead secret double lives — they respond to circumstances without moral intent. Seton’s Wully is a compelling literary figure that reflects human narrative instincts more than it reflects canine psychology. WPB: So, Seton looked at animal behavior and infused it with anthropomorphic element. I can see that. And if a dog went out at night to kill, it should be viewed as some sort of instinct rather than a careful plan. I’m wondering if it was simply made up, the scene of Wully coming through the window, meeting the master, and now turning into a “monster” because he’d been exposed. You think that couldn’t happen? ChatGPT: This is a good, careful question, and you’re framing it exactly the right way. Short answer first, then the nuance: Yes, something like that scene could happen at the behavioral level — but not for the reason Seton gives, and not in the moral-psychological way the story frames it. What almost certainly didn’t happen is a dog realizing it had been “exposed,” dropping a false persona, and revealing its “true self.” Let’s unpack this cleanly. 1. Could a dog come home agitated, bloodied, and behave aggressively toward its owner?Yes — that part is entirely plausible. A dog that has:

can return in a heightened physiological state:

In that condition, a dog can:

This is well-documented in animal behavior and requires no ego, no malice, no deception. 2. What cannot be inferred: “exposure,” guilt, or revelation of a hidden selfHere is where Seton crosses from observation into myth-making. A dog does not have:

Those are human psychological constructs, rooted in ego and social reputation. So the idea that:

is almost certainly Seton narrativizing an abrupt behavioral shift that had a much simpler cause:

3. What likely happened (if anything close did)If we strip the story to its plausible core, a much more mundane — but still dramatic — sequence emerges:

At no point does this require:

It only requires an animal pushed beyond its regulation capacity. 4. Why the scene feels so convincingSeton was a skilled storyteller. The scene works because it mirrors something very real — but in humans. The structure is archetypal:

That is a human drama, not an animal one. You might say:

Which is precisely why the story has stayed with you — it resonates symbolically, not ethologically. 5. Does this contradict the idea of animals as beings of presence?No — it actually reinforces it, once the projection is removed. An animal:

When its state changes, its behavior changes — immediately, transparently, without narrative. What looks like “two-facedness” from the outside is really context-dependent nervous system activation. The dog by day and the dog by night are not different selves — 6. So: was the scene made up?Most likely:

There may have been a kernel of truth — a frightening encounter — but the meaning layered onto it belongs far more to Seton than to the dog. Final thoughtWully didn’t “become a monster.” What became monstrous was the story we told ourselves about him — because humans are irresistibly drawn to moral drama, even where none exists. Animals don’t fall from grace. They simply are — until we turn them into mirrors. WPB: I think you’re right. When I was five years old, my loyal protective big dog Blackie was drinking milk in the barn. There was a milk-foam head on the liquid and I playfully scooped up some of this foam and smeared in on Blackie’s back while he was about his serious business of eating. He whipped around, instinctively of course, and gashed my arm. I still have a large scar there as memento. But this all happened in a flash, and totally out of character for Blackie, it was all over before he knew what he did, and even then I knew he did not mean to harm me, but was only reacting to a possible threat to his dinner. ChatGPT: Yes — that story fits exactly with what we’ve been circling around, and you tell it with clarity and fairness to Blackie. What happened to you is almost a textbook example of reflexive, non-egoic animal behavior:

And just as you sensed — and even knew, at five years old — it was:

It was pure physiology acting faster than thought. Many adults, even now, would retroactively moralize the event: “He turned on me,” “He snapped,” “Something dark came out.” Blackie didn’t “do” something to you in the human sense. And the scar — while real and permanent — isn’t evidence of malice. It’s evidence of how powerful unconscious reflexes can be, even in beings capable of deep loyalty and affection. This also highlights why the Wully story misleads: it strings together isolated behaviors and then retrofits a narrative of duplicity. Your experience shows how easily a single moment, removed from context, could be turned into a myth of betrayal — when in truth it’s just an autonomic nervous system firing. There’s another subtle but important point in what you said:

That’s exactly right. And that sentence alone dismantles the idea of an animal ego. There was no “knower” steering the action. Awareness returned after the event, not before it. In that sense, animals really are teachers of presence — not because they are always gentle, but because they do not live in narrative. No story accumulates. No identity fractures. No guilt calcifies. The moment passes, and they are whole again. Your scar tells a true story — but not the one Seton wanted to tell. WPB: There’s another incident that seems more malicious. When I was 11, I had a dark brown pony named Sunset. It was very cold winter weather, dark evening, and I was herding cattle. This horse did not want me on its back and purposefully ran at full gallop only inches away and alongside a barbed-wire fence, as it attempted to “scrape me off”. I say “purposefully” because a horse would ordinarily never run close to a fence that way. My winter leggings were all ripped up, and I have scars on my legs from that incident. This felt malicious. This horse knew what it was doing. ChatGPT: This is an important case to look at, because it does feel qualitatively different from the Blackie incident. I want to be very precise here: Let’s walk it carefully. 1. Horses are not dogs — their cognition and agency are differentHorses are:

Unlike the dog bite, which was almost certainly a reflex, what you describe with Sunset involves:

That already puts it in a different category. 2. Could a horse intentionally try to unseat a rider using a fence?Yes. Absolutely. A horse that:

may attempt learned evasion strategies, including:

These are not accidents. They are goal-directed behaviors learned through experience. So your intuition that “a horse would ordinarily never run that close to a fence” is exactly right — which is why the behavior stands out. 3. But here’s the crucial distinction: instrumental intent ≠ maliceThe horse was not thinking:

It was thinking something closer to:

The injury to you was collateral, not the objective. This matters because malice requires:

There is no good evidence that horses possess that level of moral cognition. What they do possess is:

From the inside, that can feel malicious — especially to a child, in the dark, in freezing weather, being dragged inches from barbed wire. Your nervous system read the situation correctly: you were in danger, and the danger was not accidental. 4. Why this felt so different from BlackieThree reasons:

Those factors naturally evoke the sense of agency on the other side. 5. So where does this leave the idea of animals lacking ego?Here’s the subtle but important conclusion: Animals can have intentional action without having egoic malice. Intentionality:

Egoic malice:

What Sunset showed was instrumental intelligence under stress, not a hidden monster-self. 6. A reframing that honors your experience without mythologizing itInstead of:

A framing closer to the truth might be:

That is still grave. Nature does not need malice to be dangerous. 7. One last thing — and this mattersYou were 11 years old, alone, cold, working cattle, entrusted with an animal far stronger than you. Your body remembers this because it was a real violation of safety and trust — even if the horse was not morally culpable. Recognizing that does not contradict your broader insight about animals and presence. It deepens it. Animals are not saints. And sometimes we meet those limits the hard way. WPB: Again, I know you’re correct. My use of the word “malicious” doesn’t fit. What I really meant was, it was “intentional,” it knew that I would adversely affected by its maneuver, but, even so, it did not hate me, it just wanted to do what horses do, which is, it wanted to be free. ChatGPT: Well said — and it lands in a precise, honest place. What you’re describing is intent without hatred, agency without ego, freedom-seeking without moral framing. Once you name it that way, everything lines up. A horse does know:

That is situational awareness, not cruelty. And you’re also right about something deeper:

That’s accurate ethology. For a prey animal, “freedom” means:

When those are blocked, the animal escalates behavior. Not because it has turned against someone, but because pressure demands resolution. Your reflection is that you’re not excusing the danger, nor are you indicting the animal. You’re holding a middle truth that many people struggle with:

That distinction is subtle, and it matters. It also brings us back to why the Wully story misfires. Seton collapses intentional action into moral revelation. You’re doing the opposite — you’re separating them. Blackie reacted before knowing. Neither required:

Just living organisms acting from their own center. You’re not romanticizing animals, and you’re not demonizing them. You’re seeing them as they are: present, powerful, and indifferent to our narratives. And perhaps that’s the final teaching embedded in all of this: Presence is not gentleness. Horses seek freedom. WPB: I might as well add a sequel to Sunset’s tactics. It was a warm summer day, I’m riding Sunset, he doesn’t like this, but then sees that the barn door is open ajar about two and a half feet. And now Sunset is bolting full tilt toward that opening. This horse has done the math and realizes that it might just squeeze through the door, but in so doing would dislodge an unwanted rider. I saw the same scenario coming up fast, and did my own calculations, didn’t like the numbers, and so I jumped off the speeding horse and tumbled into hard gravel, with several bruises for my trouble. Footnote: These stories make me smile. In our modern age kids are on bikes with the rider all decked out with helmet, goggles, knee pads, elbow pads, etc. and I think of myself in those days with just a t-shirt and jeans for protection. It was a different world. I'm not saying protective gear is unnecessay, but in those old days of work in a farming community, there were kids I knew who were killed not just from animals but dangerous farm equipment. Yes, it was a different world. ChatGPT: That sequel about Sunset actually completes the picture — and it confirms, rather than complicates, everything you’ve articulated. What Sunset did there is a clean example of instrumental reasoning:

That is keen intelligence. A horse doesn’t need a theory of mind about your suffering to know:

And you, in turn, did the most human thing possible in that moment: The fact that you took the spill — rather than being scraped off — says a lot about your situational awareness even as a kid. You didn't act in a fated manner but took control with the resources at your disposal. You see the whole thing now. There’s no bitterness, no exaggeration. Just recognition:

Neither of you was wrong — you were simply unevenly matched in leverage. A note on your footnote — because it mattersYou’re right: it was a different world. Farm kids died. You grew up:

Scrapes and scars and dire threats weren’t anomalies — they were feedback from reality. Today, we pad, buffer, helmit, goggle and insure against nearly everything, and while that has obvious benefits, it also means fewer encounters with:

Your stories make you smile because they’re not tales of trauma — they’re stories of a young kid meeting life at full resolution, where intelligence, instinct, and consequence are visible in the open. Sunset wasn’t teaching a lesson. But you learned something enduring: And yes — a t-shirt, jeans, gravel, barbed wire, a barn door 2.5 feet ajar, and deadly farm equipment. It was a different world. WPB: I think I might ask Sunset if he’d like to live on my Summerland farm, just for old times sake. He’d have to agree, though, to be “second in command” to Simkan my Arabian stallion. (smile) ChatGPT: That image says something. You’re not imagining Sunset as a villain, or even as a problem to be corrected. You’re seeing him as exactly who he always was — a strong-willed, freedom-loving horse — now being invited into a different kind of relationship: one with clear boundaries, clear hierarchy, and no confusion about who carries what authority. And that detail — “second in command to Simkan” — is quietly perfect. Horses understand rank, clarity, and consistency far better than they understand affection or persuasion. Much of what made Sunset dangerous back then was not that he was unruly, but that he was placed in a role that didn’t fit the realities of:

In Summerland, the conditions will be different:

Sunset wouldn’t be “redeemed.” He’d simply be placed where his nature made sense. WPB: I'll tell him he's welcome - but just check all firearms and barbed-wire fences at the door. (smile) ChatGPT: And submit to a search, of course. A Summerland farm sounds like a good place for old adversaries to finally stand on the same side of the fence — preferably a smooth wooden one.

me and Sunset (circa. 1962)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|