|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Soulmate, Myself:

Editor's note: This writing begins with a discussion of Pythagorean harmonics but takes us to a wider field of all things harmonious to one's core being; the greatest expression of which is Twin Soul eternal marriage.

The following is from Dr. Robinson's lecture series, The Great Ideas Of Psychology: Pythagoras believed eternal truth is embedded in harmonic relationship. The ancient Greek, Pythagoras, (ca.580 – ca.500 BC) taught that ultimate truth expresses itself in number; that is, mere appearance is a source of deception. Whatever appears to us through our sensory apparatus must be fleeting, transitory, ultimately decomposable into mere dust and rubbish. The eternal truths are found relationally, in the form of harmonic relationships, rational order, and number. It is said that the Pythagoreans thought that all physical reality springs from the first four positive integers, because – 1 is the numerical source of a point; 2 constitutes the possibility of a line; 3 constitutes the possibility of a plane [triangle]; and 4 constitutes the possibility of a solid… Why does music sound harmonious or discordant? It’s also Pythagoras, we are told, who worked out the original theory of harmony in music and the harmonic scales… Here again was evidence that the human soul is tuned in a certain way, to match up with precise mathematical relationships. Music that is composed and played according to these core mathematical relationships will be heard as harmonic. The reason it sounds “right” [to us] is because (1) the harmonies of the rational soul and (2) the acoustic harmonies achieved … enjoy a hand-in-glove relationship. Philosophy, at its best, is the search for eternal, unchanging, truth. This is a background consideration, and what it encourages the Socratics to argue for is the view that the kind of truth the philosophers should search for is not to be found in the transitory world of things, that which can be degraded, give rise to illusions, and preposterous beliefs. No, what the philosopher, the true lover of wisdom, should seek is the immutable, the eternal, that which cannot change – and this can never be anything material.

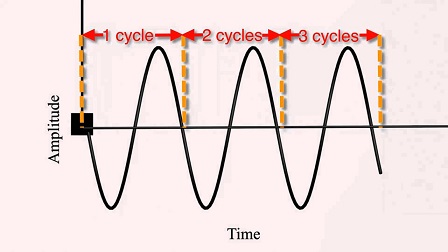

Elenchus. Pythagoras spent most of his life constructing a mathematics-based view of reality, but it's complicated, and we can hardly address a particle of it here. Kairissi. He’s most famous, arguably, for his theorem concerning the relationship of the sides of a right triangle. We won’t touch on that here, only to say that it’s another example of ratios representing an unseen reality. E. And his math-based conception of music is no small item, either. I’m not a music major, and so my knowledge of his theory of harmonics is rather sparse, and what I say here might constitute the briefest survey. K. One could spend a lifetime exploring this subject - and I would like to suggest that, when we get to Summerland, you and I should delve deeply into music theory. But, for purposes at hand, let’s define one or two basic elements of music harmonics. E. Dr. Robinson said that, when two sounds are in “harmonious” relationship, their frequencies will be expressed as a ratio of whole numbers; if they're fractions, the resultant sound will be "discordant." K. That's quite a discovery, but let’s see if we can make this somewhat clear. On a piano, to move from one “A” note, with a frequency of 440 hertz, to the next A” note – eight notes apart, an octave higher – we find that the second “A” will have a frequency of 880 hertz. In other words, as 880 is two times 440, these two notes vibrate at a 2:1 ratio; and, if played together, will produce a “harmonious” comingled sound. E. Allow me to define “hertz.” It’s a basic unit of vibrational frequency. Music, of course, is a sound, and all sounds move with vibrational frequency. Think of a sine wave:

E. Sound moves as a kind of vibrational wave; high to low represents 1 wave cycle. K. And 1 hertz means 1 cycle per second. E. The first "A" note in our example was vibrating at 440 hertz, that is, 440 cycles per second. The more cycles per second, the higher the pitch of the sound. K. The 880 hertz "A" is vibrating twice as fast as the first "A," but, even so, combines "harmoniously" with it. E. There's endless math and volumes to learn here, but I think we should end our tech-discussion while we're ahead as I've now exhausted my music-math knowledge. K. As we've said, we could spend many years studying these things, there's so much, but I think what we want to focus on is getting at the underlying meaning.

K. I’ve been thinking about this, and I finally have a vague sense of what I want to say. I’m still not sure, though. E. This is one of those subjects that we just need to talk it out. Why don’t you begin? What’s uppermost in your mind about this? K. Pythagoras has a really important idea here, but he’s getting part of it wrong. E. What's the problem? K. He’s putting too much emphasis on the math part. He's making it primary. We talked about some of this in the “certainty” article; for example,

'at its deepest level, reality is mathematical in nature'

K. And so the question will be asked, is there anything wrong with Pythagoras’ statement? We have the math equations which explain how music sound waves operate and interact with each other, and so, many would say, it appears that the underlying nature of music is mathematical. E. How would you respond to this? K. I would say that there’s an aspect to almost any subject that might be quantified or explained by mathematics. Case in point, when little Johnny eats his “sugar frosted flakes” in the morning, we can use mathematics to describe the event in terms of how much was eaten, the rate of spoonsful per minute ingested, the average size and weight of each cornflake – on and on. However, all this math-based information does not mean that breakfast is primarily “mathematical in nature.” a language of size, distance, and quantity E. Very good. Excellent. We need to keep in mind that mathematics is a language of science. It helps us talk about how fast, how far, how much, how big, and the like. And we can employ questions such as these for almost any topic. K. Yes, math is a language, a mode of communication and expression. Math data and equations are like statements or words in a math-based discourse. But Krishnamurti warned us about confusing a word with what is. He said, for example, that the word “God” is not God. Editor's note: Mere assertion is not dispositive to reality. People say all sorts of things, including "I believe in God," but this "God," for many, is something external, a mere word, just a concept in the head, a belief-system, not a living entity-force within. E. And the word "cheesecake" is not real dessert. You could write a book about it, claim to be an authority, be interviewed on Oprah as an expert, but if you've never tasted it, then you have no idea. The word is not the thing. It would be like going to a restaurant and eating the menu, the words about cheesecake, instead of ordering the actual high-calorie delight.

E. Kriss, summarize why "the word is not the thing" is important to understand here. K. Math-facts about music, although beautiful and elegant, do not constitute a basis of reality. Math-facts are merely quantitative "words," thought forms, just mental constructs. All these help us to discuss how things work, but let's not "eat the menu." E. Even if the glossy photos are tempting. So, ok then, where does this leave us? K. Pythagoras is rightfully credited with many insights in math and music. However, to say that music is mathematical in its nature goes too far and is very wide of the mark. Pythagoras was so impressed with the beauty of mathematics that he worshiped it as a god. This is why he spoke of the “divinity of number.”

K. This guy seriously needs to lighten up. E. (small smile) K. His mathematics are a marvel, no denying it, however, math is just an indicator of something far deeper, and far more wondrous. 'the thing in itself' E. I’m reminded of how Kant judged the world. He said that something we access with the five senses is the “phenomenon”; but behind this mere appearance, this illusion of things, he said, lies the “noumenon,” the reality, the thing in itself. K. Yes, this is what I want to say. We want to get at “the thing in itself” and not just illusionary surface-appearance; not just a mathematical "word" or expression but the actual item. E. And what is that actual item? K. I need your help to bring this into sharper view.

E. Why don’t we go back to Dr. Robinson’s lecture and remind ourselves of what provoked his interest. He said that there's... evidence that the human soul is tuned in a certain way, to match up with precise mathematical relationships. Music that is composed and played according to these core mathematical relationships will be heard as harmonic. The reason it sounds “right” [to us] is because (1) the harmonies of the rational soul and (2) the acoustic harmonies achieved … enjoy a hand-in-glove relationship. K. Now we're getting to something really important. Why does some music sound harmonious and pleasant, but some strikes us as discordant and harsh? E. We don't like certain sounds, like chalk grating on a blackboard. It makes us wince. K. And the question is why? E. Why do some sounds feel "right" to us? K. Something is going on down below or out of sight to make this happen. We hear two or more notes played together, and if their ratios of vibration can be expressed with whole numbers, then we’ll deem the ensuing sound to be musically harmonious.

K. Do you have any new insight on our question? E. Actually, now I have more questions. K. I was afraid of that. E. Dr. Robinson stated that there’s “evidence that the human soul is tuned in a certain way,” and this is why a certain musical harmony “sounds right” to us. K. It’s as if we’ve been programmed, at the level of core being, to respond to or resonate with a built-in sense of propriety. hidden blueprints E. Yes. Good. Or, we might say, there’s a “hidden blueprint” leading, directing us, to feel “right” or “good” about certain elements of life - and to recoil from the “discordant.” K. The concept of the “hidden blueprint” is very important and takes us to the research of Dr. Rupert Sheldrake. He called these “hidden blueprints” morphic fields. We presented their extensive evidence on the "evolution" page. Concerning these "hidden blueprints," Dr. Sheldrake said: "The word ‘morphic’ comes from the Greek word ‘morphe,’ meaning form or shape. These are fields that order self-organizing systems … These fields organize energy… [This is the] big picture.” K. These "hidden blueprints" organize energy, and we find ourselves reflecting this cloaked programming, and this is why certain things feel "right" or "good" to us. E. We're reminded of Krishnamurti's dictum that the enlightened person "has no choice" but will simply flow in the energy of life. K. Elenchus, let’s bring this back to what Pythagoras said about music. E. We need to do that, but first, allow me a moment – I said that I had more questions. What I mean is, we’re beginning to see that there’s a “hidden blueprint” leading us to feel certain music as harmonious and other music as discordant. But the inner guidance, the “attunement of the soul” that Dr. Robinson spoke of, doesn’t stop with a judgment of what is “harmonious” music. K. (silence) E. The “hidden blueprints” direct all major aspects of our sensibilities and what we – enlightened persons – consider to be moral, worthy, righteous, and spiritual. K. Now we’re getting close to the mother-lode. Say more on this, Elenchus. E. And so the larger field of this questioning is not just “Why do we feel that such-and-such music is good and harmonious?” but “Why do we say that a blossoming rose, or a sunset, or a woman, is beautiful?” or “Why is that joke funny, and why do we laugh at all?” or “Why does the mature mind want to engage in service projects, to self-abnegate, and to work for the common good?”; further, “Why do we virtually idolize the super-hero servants?”

heroic altruism: “ambitious for the sake of others”

K. Yes, of course. And to these few questions we could add a hundred, or a thousand, more. Why do human beings, in a mature state, gravitate toward these proclivities? What is the “hidden blueprint,” a seeming pre-programming, driving all this, what we deem to be, high-minded and virtuous humanism? E. The “hidden blueprint” inciting all this must really be something. And to claim that it’s a “divinity of number,” I would say, sounds pretty lame and shallow. K. I think we know the answer. The great quantum physicists would assert that a universal consciousness, not matter, is the ground of all being. And we would say this is correct. However, rather than “universal consciousness," I prefer “the mind of God”-- and this mind of God, not mathematics, is the basis of all reality. E. Our entire discussion brings us to declare that the “hidden blueprint” is our status of having been “made in the image,” a hidden form or ideal image of God. K. "Made in the image" is the embedded programming. It is more than mere mental conditioning due to "nomos," one's culture and upbringing. All these aspects, these refinements, of the evolved, intellectual, and spiritual man or woman, in fact, reflect the mind of Mother-Father God. E. And, in this light, let us add one more question to our list: “Why do a woman and man fall in love?” – and, if they really mean it, not just for a good time, or even a good life, but, what they really want is, for all time – the eternal Twin Soul marriage. K. (sighing) Sounds like one more way we’re like the Divine Parent(s).

some things are too wonderful to be untrue K. Elenchus, if I may, I’d like to add a final word. E. I'd love to hear it. K. A long time ago, in the closing remarks of “Prometheus,” I stated that “some things are too wonderful to be untrue.” E. A beautiful phrase. K. It was true for me then, however, with all that we've suffered since those days of immaturity, it’s far more meaningful today. Some will scoff and deny, but I’m not concerned about their criticism. I know what I feel, and what I’ve seen, with the eyes of the soul. At times, I’m given a vision of the future, the great joy you and I will yet share simply to live and love together. I don’t believe it’s possible for me to be mistaken about this sense of coming bliss, it feels so right and so real to me. And when I say that “some things are too wonderful to be untrue,” I mean that my feelings are so deep and so profound that they can’t be illusion. In our discussion today, we spoke of proclivities which could not exist but for their basis in “hidden blueprints” and the mind of God. This is what I mean. I could not feel what I feel if I had not been made – “made in the image” – to feel them. And so, yes, “some things are too wonderful to be untrue.”

|

||||

|

|