|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

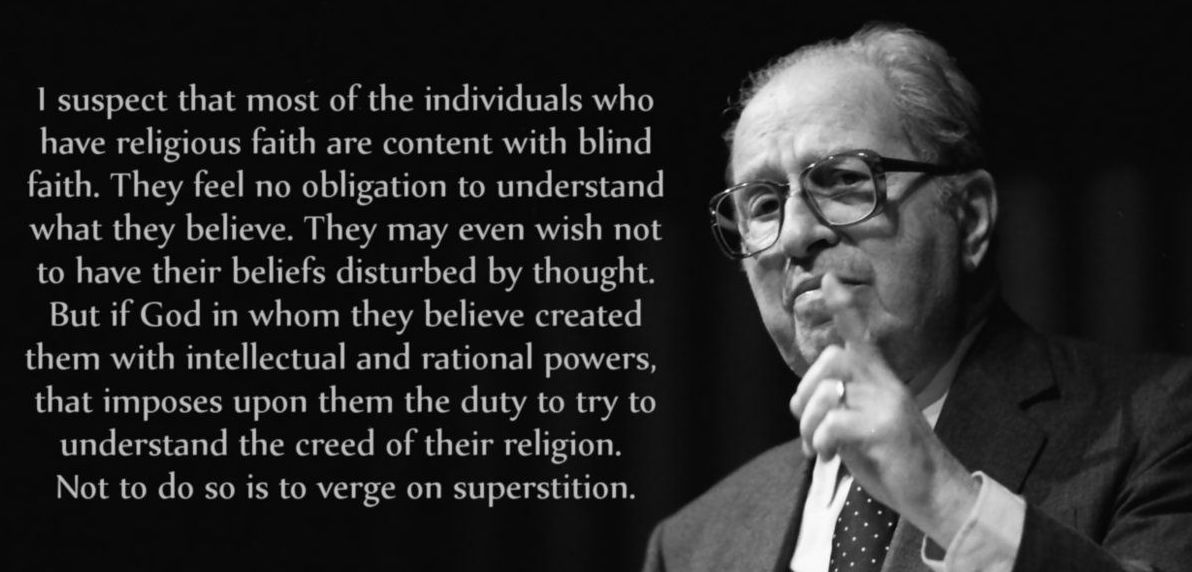

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler (1902 - 2001)

NOT everyone knows Josiah Royce's definition of a liar as a man who willfully misplaces his ontological predicates, but everyone who has ever told a lie will recognize its accuracy. To restate the definition less elegantly, lying consists in saying the contrary of what one thinks or believes. To speak truthfully we must make our speech conform to our thought, we must say that something is the case if we think it is, or that it is not, if we think it is not. If we deliberately say "is" when we think is not, or say "is not" when we think is, we lie. Of course, the man who speaks truthfully may in fact say what is false, just as the man whose intent is to falsify may inadvertently speak the truth. The intention to speak one's mind does not guarantee that one's mind is free from error or in possession of the truth. Herein lies the traditional distinction between truth as a social and as an intellectual matter. What Dr. Johnson calls moral truth consists in the obligation to say what we mean. In contrast what he calls physical truth depends not on the veracity of what we say but on the validity of what we mean. The theory of truth in the tradition of the great books deals largely with the latter kind of truth. The great issues concern whether we can know the truth and how we can ever tell whether something is true or false. Though the philosophers and scientists, from Plato to Freud, seem to stand together against the extreme sophistry or skepticism which denies the distinction between true and false or puts truth utterly beyond the reach of man, they do not all agree on the extent to which truth is attainable by men, on its immutability or variability, on the signs by which men tell whether they have the truth or not, or on the causes of error and the means for avoiding falsity. Much that Plato thinks is true Freud rejects as false. Freud searches for truth in other quarters and by other methods. But the ancient controversy in which Socrates engages with the sophists of his day, who were willing to regard as true whatever anyone wished to think, seems to differ not at all from Freud's quarrel with those whom he calls "intellectual nihilists." They are the persons who say there is no such thing as truth or that it is only the product of our own needs and desires. They make it "absolutely immaterial," Freud writes, "what views we accept. All of them are equally true and false. And no one has a right to accuse anyone else of error." Across the centuries the arguments against the skeptic seem to be the same. If the skeptic does not mind contradicting himself when he tries to defend the truth of the proposition that all propositions are equally true or false, he can perhaps be challenged by the fact that he does not act according to his view. If all opinions are equally true or false, then why, Aristotle asks, does not the denier of truth walk "into a well or over a precipice" instead of avoiding such things. "If it were really a matter of indifference what we believed," Freud similarly argues, "then we might just as well build our bridges of cardboard as of stone, or inject a tenth of a gramme of morphia into a patient instead of a hundredth, or take tear-gas as a narcotic instead of ether. But," he adds, "the intellectual anarchists themselves would strongly repudiate such practical applications of their theory." Whether the skeptic can be refuted or merely silenced may depend on a further step in the argument, in which the skeptic substitutes probability for truth, both as a basis for action and as the quality of all our opinions about the real world. The argument takes different forms according to the different ways in which probability is distinguished from truth or according to the distinction between a complete and limited skepticism. Montaigne, for example, seems to think that the complete skeptic cannot even acknowledge degrees of probability to be objectively ascertainable without admitting the criterion of truth, whereas Hume, defending a mitigated skepticism, offers criteria for measuring the probability of judgments about matters of fact.

Not only do the great authors (with the possible exception of Montaigne and Hume) seem to be unanimous in their conviction that men can attain and share the truth--at least some truths--but they also appear to give the same answer to the question, What is truth? The apparently unanimous agreement on the nature of truth may seem remarkable in the context of the manifold disagreements in the great books concerning what is true. As already indicated, some of these disagreements occur in the theory of truth itself -- in divergent analyses of the sources of error, or in conflicting formulations of the signs of truth. But even these differences do not affect the agreement on the nature of truth. Just as everyone knows what a liar is, but not as readily whether someone is telling a lie, so the great philosophers seem able to agree on what truth is, but not as readily on what is true. That the definitions--of lying and of truth--are intimately connected will be seen from Plato's conception of the nature of truth as a correspondence between thought and reality. If truthfulness, viewed socially, requires a man's words to be a faithful representation of his mind, truth in the mind itself (or in the statements which express thought) depends on their conformity to reality. A false proposition, according to Plato, is "one which asserts the non-existence of things which are, and the existence of things which are not." Since "false opinion is that form of opinion which thinks the opposite of the truth," it necessarily follows, as Aristotle points out, that "to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true," just as it is false "to say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is." In one sense, the relation between a true statement and the fact it states is reciprocal. "If a man is," Aristotle declares, then "the proposition in which we allege that he is, is true; and conversely, if the proposition wherein we allege that he is, is true, then he is." But the true proposition "is in no way the cause of the being of the man," whereas "the fact of the man's being does seem somehow to be the cause of the truth of the proposition, for the truth or falsity of the proposition depends on the fact of the man's being or not being." THIS SIMPLE STATEMENT about the nature of truth is repeated again and again in the subsequent tradition of western thought. What variation there is from writer to writer seems to be in phrasing alone, though the common insight concerning truth as an agreement or correspondence between the mind and reality may occur in the context of widely varying conceptions concerning the nature of the mind and of reality or being. But others, like Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, and Spinoza, adopt the conception of truth as an agreement between the mind and reality. Falsehood occurs, says Augustine, when "something is thought to be which is not." According to Aquinas, "any intellect which understands a thing to be otherwise than it is, is false." Truth in the human intellect consists "in the conformity of the intellect with the thing." The same point is implied, at least, in Descartes' remark that if we do not relate our ideas "to anything beyond themselves, they cannot properly speaking be false." Error or, for that matter, truth can only arise in "my judging that the ideas which are in me are similar or conformable to the things which are outside me." Spinoza states it as an axiom rather than a definition that "a true idea must agree with that of which it is the idea." Making a distinction between verbal and real truth, Locke writes: "Though our words signify nothing but our ideas, yet being designed by them to signify things, the truth they contain, when put into propositions, will be only verbal, when they stand for ideas in the mind that have not an agreement with the reality of things." Precisely because he considers truth to consist "in the accordance of a cognition with its object," Kant holds that, so far as the content (as opposed to the form) of a cognition is concerned, it is impossible to discover a universal criterion of truth. We shall return to Kant's point in a subsequent discussion of the signs of truth, as also we shall have occasion to return to Locke's distinction between real and verbal truth. Neither affects the insight that truth consists in the agreement of our propositions or judgments with the facts they attempt to state, unless it is the qualification that truth so defined is real, not verbal. In his Preface to The Meaning of Truth, James comments on the excitement caused by his earlier lectures on pragmatism, in which, offering the pragmatist's conception of truth, he had spoken of an idea's "working successfully" as the sign of its truth. He warns his critics that this is not a new definition of the nature of truth, but only a new interpretation of what it means to say that the truth of our ideas consists in "their agreement, as falsity means their disagreement, with reality. Pragmatists and intellectualists," he adds, "both accept this definition as a matter of course. "To agree in the widest sense with reality," James then explains, "can only mean to be guided either straight up to it or into its surroundings, or to be put into such working touch with it as to handle either it or something connected with it better than if we disagreed. Better either intellectually or practically . . . Any idea that helps us to deal, whether practically or intellectually, with either the reality or its belongings . . . that fits, in fact, and adapts our life to the reality's whole setting, will agree sufficiently to meet the requirement. It will be true of that reality." Without enlarging on its meaning as James does, Freud affirms that the ordinary man's conception of truth is that of the scientist also. Science, he says, aims "to arrive at correspondence with reality, that is to say with what exists outside of us and independently of us... This correspondence with the real external world we call truth. It is the aim of scientific work, even when the practical value of that work does not interest us."

THE DEFINITION OF TRUTH as the agreement of the mind with reality leaves many problems to be solved and further explanations to be given by those who accept it. As James indicates, the theory of truth, begins rather than ends with its definition. How do we know when our ideas--our statements or judgments--correspond with reality? By what signs or criteria shall we discover their truth or falsity? To this question the great books give various answers which we shall presently consider. There are other problems about the nature of truth which deserve attention first. For example, one consequence of the definition seems to be that truth is a property of ideas rather than of things. Aristotle says that "it is not as if the good were true and the bad were in itself false"; hence "falsity and truth are not in things . . . but in thought." Yet he also applies the word "false" to non-existent things or to things whose appearance somehow belies their nature. Aquinas goes further. He distinguishes between the sense in which truth and falsity are primarily in the intellect and secondarily in things. The equation between intellect and thing, he points out, can be looked at in two ways, depending on whether the intellect is the cause of the thing's nature, or the nature of the thing is the cause of knowledge in the intellect. When "things are the measure and rule of the intellect, truth consists in the equation of the intellect to the thing . . . But when the intellect is the rule or measure of things, truth consists in the equation of things to the intellect" -- as the product of human art may be said to be true when it accords with the artist's plan or intention. Thus "a house is said to be true that fulfills the likeness of the form in the architect's mind." Aquinas' conclusion--that "truth resides primarily in the intellect and secondarily in things according as they are related to the intellect as their source"--at once suggests the profound difference between truth in the divine and in the human intellect. The difference is more than that between infinite and finite truth. The distinction between uncreated and created truth affects the definition of truth itself. The definition of truth as an equation of thought to thing, or thing to thought, does not seem to hold for the divine intellect. The notion of "conformity with its source," Aquinas acknowledges, "cannot be said, properly speaking, of divine truth." Divine truth has no source. It is not truth by correspondence with anything else. Rather it is, in the language of the theologian, the "primal truth." "God Himself, Who is the primal truth ... is the rule of all truth," and "the principle and source of all truth."

For Locke, verbal truth is "chimerical" or "barely nominal" because it can exist without any regard to "whether our ideas are such as really have, or are capable of having, an existence in nature." The signs we use may truly represent our thought even though what we think or state in words is false in fact. Hobbes takes a somewhat contrary view. "True and false," he writes, "are attributes of speech, not of things. And where speech is not, there is neither truth nor falsehood." What is the cause of truth in speech? Hobbes replies that, since it consists "in the right ordering of names in our affirmations," a man needs only "to remember what every name he uses stands for." If men begin with definitions or "the settling of significations," and then, abide by their definitions in subsequent discourse, their discourse will have truth. From want of definitions or from wrong definitions arise "all false and senseless tenets." Agreement with reality would seem to be the measure of truth for Hobbes only to the extent that definitions can be right or wrong by reference to the objects defined. If definitions themselves are merely nominal and have rightness so far as they may be free from contradiction, then truth tends to become, more than a property of speech, almost purely logistical -- a matter of playing the game of words according to the rules. Reasoning is reckoning with words. It begins with definitions and if it proceeds rightly, it produces "general, eternal and immutable truth ... For he that reasoneth aright in words he understandeth, can never conclude in error." Hobbes' position seems to have a bearing not only on the issue concerning verbal and real truth, but also on the question whether the logical validity of reasoning makes the conclusion it reaches true as a matter of fact. Some writers, like Kant, distinguish between the truth which a proposition has when it conforms to the rules of thought and the truth it has when it represents nature. Valid reasoning alone cannot guarantee that a conclusion is true in fact. That depends on the truth of the premises--upon their being true of the nature of things. Aristotle criticizes those who, accepting certain principles as true, "are ready to accept any consequence of their application. As though some principles," he continues, "did not require to be judged from their results, and particularly from their final issue. And that issue . . . in the knowledge of nature is the unimpeachable evidence of the senses as to each fact."

That seems be the position of Hobbes and Hume, both of whom take geometry as the model of truth. For them statements of fact about real existence are at best probable opinions. For others, like James, there can be truth in the natural sciences, but such empirical truth is distinct in type from what he calls the "necessary" or "a priori" truths of mathematics and logic. Does the definition of truth as agreement with reality apply to all kinds of truth, or only truths about the realm of nature? The question has in mind more than the distinction between mathematics and physics. It is concerned with the difference between the study of nature and the moral sciences, or between the theoretic and the practical disciplines. "As regards nature," writes Kant, "experience presents us with rules and is the source of truth," but not so in ethical matters or morality. A theoretic proposition asserts that something exists or has a certain property, and so its truth depends on the existence of the thing or its real possession of an attribute; but a practical or moral judgment states, not what is, but what should occur or ought to be. Such a judgment cannot be true by correspondence with the way things are. Its truth, according Aristotle, must consist rather "in agreement with right desire." On this theory, all that remains common to speculative and practical truth is the conformity of the intellect to something outside itself -- to an existing thing or to desire, will, or appetite. Stressing the difference, Aquinas declares that "truth is not the same for the practical as for the speculative intellect." The "conformity with right appetite" upon which practical truth depends, he goes on to say, "has no place in necessary matters, which are not effected by the human will, but only in contingent matters which can be effected by us, whether they be matters of interior action or the products of external work." In consequence, "in matters of action, truth or practical rectitude is not the same for all as to what is particular, but only as to the common principles"; whereas in speculative matters, concerned chiefly with necessary things, "truth is the same for all men, both as to principles and as to conclusions."

In the controversy over the pragmatic theory of truth, in which James engages with Bradley and Russell, some confusion tends to result from the fact that James seldom discusses what truth is except in terms of how we know what is true, while his opponents often ignore the signs of truth in discussing its nature. The important point for James is not that truth consists in agreement with reality, but that "true ideas are those we can assimilate, validate, corroborate, and verify." Whether we can assimilate or validate or verify an idea in turn depends upon its consequences, either for thought or action, or what James calls "truth's cash-value in experiential terms." "The test of real and vigorous thinking," writes J. S. Mill, "the thinking which ascertains truths instead of dreaming, is successful application to practice." In similar vein, Bacon says that "of all the signs there is none more certain or worthy than that of the fruits produced, for the fruits and effects are the sureties and vouchers, as it were, for the truth of philosophy." The man who supposes that the end of learning lies in contemplation of the truth will "propose to himself as the test of truth, the satisfaction of his mind and understanding, as to the causes of things long since known." Only those who recognize that "the real and legitimate goal of the sciences is the endowment of human life with new inventions and riches," will submit truth to the test of its leading "to some new earnest of effects." To take effects as "pledges of truth" is, for Bacon, equivalent to declaring that truth and utility are "perfectly identical." Verification by appeal to observation or sensible evidences may be regarded as one way of testing the truth of thought in terms of its consequences, but it also involves the principle of contradiction as a criterion of truth. When Aristotle recommends, for example, that we should accept theories as true "only if what they affirm agrees with the observed facts," he is saying that when the truth of a particular perception is indisputable, because the observed fact is evident, the general or theoretical statement which it contradicts must be false. But the principle of contradiction as a criterion of truth goes further than testing theories by their consistency with observation. One of two contradictory statements must be false and the other must be true "if that which it is true to affirm is nothing other than that which it is false to deny." Even a single statement may show itself false by being self-contradictory, and in consequence its opposite can be seen to be true. What Aristotle calls axioms, or self-evident and indisputable truths, are those propositions immediately known to be true, and necessarily true, because their contradictories, being self-contradicatory, are impossible statements, or necessarily false. The truth of any proposition which is neither a self-evident axiom nor the statement of an evident, perceived fact, is tested, according to the principle of contradiction, by its consistency with axioms or perceptions. As opposed to consequences or effects, contradiction or consistency as a sign of truth seems to be an intrinsic criterion. But this criterion is not universally accepted. "Contradiction," writes Pascal, "is not a sign of falsity, nor the want of contradiction a sign of truth." Nor, even when accepted, is it always judged adequate to solve the problem. It is, for Kant, a "merely logical criterion of truth . . . the conditio sine qua non, or negative condition of all truth. Farther than this logic cannot go, and the error which depends not on the form, but on the content of the cognition, it has no test to discover." Some thinkers seem to rely upon an intrinsic mark by which each idea reveals its own truth or falsity. Augustine, for example, considers by what criterion he would know whether what Moses said was true. "And if I did know it," he asks, "would it be from him that I knew it? No," he replies, "but within me, in the inner retreat of my mind, the Truth, which is neither Hebrew nor Greek, nor Latin nor Barbarian, would tell me, without lips or tongue or sounded syllables: 'He speaks truth.' " For Augustine, God is the warranty of the inner voice which plainly signifies the truth. For Spinoza, the truth of an idea depends upon its relation to God. Because "a true idea in us is that which in God is adequate, in so far as He is manifested by the nature of the human mind," it follows, according to Spinoza, that "he who has a true idea knows at the same time that he has a true idea, nor can he doubt the truth of the thing"; for "he who knows a thing truly must at the same time have an adequate idea or a true knowledge of his knowledge, that is to say (as is self-evident) he must be certain." It is impossible, Spinoza maintains, to have a true idea without at the same time knowing that it is true. To the question, "How can a man know that he has an idea which agrees with that of which it is the idea?" he replies that "he knows it simply because he has an idea which agrees with that of which it is the idea, that is to say, because truth is its own standard." For what can be clearer, Spinoza asks, "or more certain than a true idea as the standard of truth? Just as light reveals both itself and the darkness, so truth is the standard of itself and of the false." Spinoza defines an adequate idea as one which, "in so far as it is considered in itself, without reference to the object, has all the properties or internal signs of a true idea." He explains, moreover, that by "internal" he means to exclude even "the agreement of the idea with its object." This, he thinks, meets the objection that "if a true idea is distinguished from a false idea only in so far as it is said to agree with that of which it is the idea, the true idea [would have] no reality or perfection above the false idea (since they are distinguished by an external sign alone), and consequently the man who has true ideas will have no greater reality or perfection than he who has false ideas only." Although Descartes and Locke also employ an intrinsic criterion of truth--not the adequacy, but the clarity and distinctness, of ideas--they do not seem to mean, as Spinoza does, that a single idea, in and of itself, can be true or false. Like Aristotle before them or Kant later, they regard a simple idea or concept as, strictly speaking, incapable of being either true or false. "Truth and falsity," writes Locke, "belong ... only to propositions" -- to affirmations or denials which involve at least two ideas; or, as Kant says, "truth and error . . .are only to be found in a judgement," which explains why "the senses do not err, not because they always judge correctly, but because they do not judge at all." Nevertheless, for Locke the clarity and distinctness of the ideas which enter into the formation of propositions enable the mind to judge intuitively and certainly of their truth. When ideas are clear and distinct, "the mind perceives the agreement or disagreement of two ideas immediately by themselves . . . Such kind of truths the mind perceives at the first sight of the ideas together by bare intuition . . . and this kind of knowledge is the clearest and most certain that human frailty is capable of."

"If we did not know," Descartes reflects, "that all that is in us of reality and truth proceeds from a perfect and infinite being, however clear and distinct were our ideas, we should not have any reason to assure ourselves that they had the perfection of being true." But once we have "recognized that there is a God . . . and also recognized that all things depend upon Him, and that He is not a deceiver," we can infer that whatever we "perceive clearly and distinctly cannot fail to be true." What, then, is the source of our errors? "I answer," writes Descartes, "that they depend on a combination of two causes, to wit, on the faculty of knowledge that rests in me, and on the power of choice or free will." Each perfect in its own sphere, neither the will nor the understanding by itself causes us to fall into error. "Since I understand nothing but by the power which God has given me for understanding, there is no doubt," Descartes declares, "that all that I understand, I understand as I ought, and it is not possible that I err in this." The trouble lies in the relation of the will to the intellect. "Since the will is much wider in its range and compass than the understanding, I do not restrain it within the same bounds, but extend it also to things which I do not understand." It is not God's fault, says Descartes, if, in the exercise of my freedom, I do not "withold my assent from certain things as to which He has not placed a clear and distinct knowledge in my understanding." But as long as "I so restrain my will within the limits of knowledge that it forms no judgment except on matters which are clearly and distinctly represented to it by the understanding, I can never be deceived." There are other accounts of error, less elaborate than Descartes', which are similar to the extent that they place the cause in some combination of human faculties rather than in their simple and separate operation. Socrates explains to Theaetetus that false opinions arise when the senses and the mind do not cooperate properly. Aristotle suggests that it is the imagination which frequently misleads the mind. Looking at the problem from the point of view of the theologian, Aquinas holds that Adam, in his state of innocence before the fall, could not be deceived. "While the soul remained subject to God," he writes, "the lower powers in man were subject to the higher, and were no impediment to their action." But man born in sin can be deceived, not because the intellect itself ever fails, but as a result of the wayward influence "of some lower power, such as the imagination or the like." Lucretius, for whom sense, not mind, is infallible, attributes error to the fault of reason, which misinterprets the veridical impressions of the senses. "What surer test can we have than the senses," he asks, "whereby to note truth and falsehood?" He explains that the mind, not the senses, is responsible for illusions and hallucinations. "Do not then fasten upon the eyes this frailty of the mind." Other writers, like Descartes, take the opposite view, that the senses are much less trustworthy than the intellect. Still others, like Montaigne, seem to find that error and fallacy, rather than any sort of infallibility, are quite natural to all human faculties, and beset sense and reason alike. "Man," says Pascal, is "full of error, natural and ineffaceable, without grace. Nothing shows him the truth. Everything deceives him. Those two sources of truth, reason and the senses, besides being both wanting in sincerity, deceive each other in turn." Considering the extremes to which men have gone in their appraisal of human prowess or frailty, Locke's moderate statement of the matter is worth pondering. "Notwithstanding the great noise made in the world about errors and opinions," he writes, "I must do mankind that right, as to say, there are not so many men in errors and wrong opinions as is commonly supposed. Not that I think they embrace the truth; but, indeed, because concerning these doctrines they keep such a stir about, they have no thought, no opinion at all . ... And though one cannot say that there are fewer improbable or erroneous opinions in the world than there are, yet this is certain, there are fewer that actually assent to them, and mistake them for truths, than is imagined."

|

||

|

|