|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

|||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Quantum Mechanics

return to "Quantum Mechanics" main-page

website: https://seatofthesoul.com

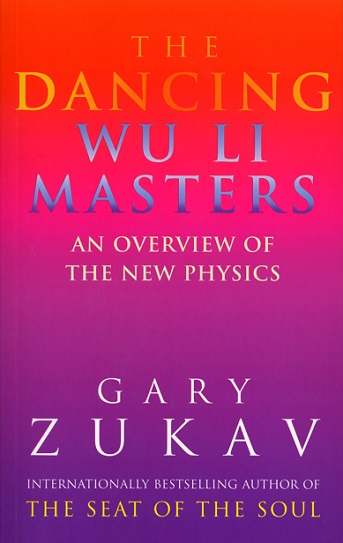

Editor’s note: “Wu Li” is the Chinese word for physics; literally, “patterns of organic energy”

Excerpts from Gary Zukav's book: There is another fundamental difference between the old physics and the new physics. The old physics assumes that there is an external world which exists apart from us. It further assumes that we can observe, measure, and speculate about the external world without changing it. According to the old physics, the external world is indifferent to us and to our needs. Galileo’s historical stature stems from his tireless (and successful) efforts to quantify (measure) the phenomena of the external world. There is great power inherent in the process of quantification. For example, once a relationship is discovered, like the rate of acceleration of a falling object, it matters not who drops the object, what object is dropped, or where the dropping takes place. The results are always the same. An experimenter in Italy gets the same results as a Russian experimenter who repeats the experiment a century later. The results are the same whether the experiment is done by a skeptic, a believer, or a curious bystander. Facts like these convinced philosophers that the physical universe goes unheedingly on its way, doing what it must, without regard for its inhabitants. For example, if we simultaneously drop two people from the same height, it is a verifiable (repeatable) fact that they both will hit the ground at the same time, regardless of their weights. We can measure their fall, acceleration, and impact the same way that we measure the fall, acceleration, and impact of stones. In fact, the results will be the same as if they were stones. "But there is a difference between people and stones,'' you might say. “Stones have no opinions or emotions. People have both. One of these dropped people, for example, might be frightened by his experience and the other might be angry. Don't their feelings have any importance in this scheme?" No. The feelings of our subjects matter not in the least. When we take them up the tower again (struggling this time) and drop them off again, they fall with the same acceleration and duration that they did the first time, even though now, of course, they are both fighting mad. The Great Machine is impersonal [it seemed]. In fact, it was precisely this impersonality that inspired scientists to strive for “absolute objectivity." The concept of scientific objectivity rests upon the assumption of an external world which is "out there" as opposed to an "I" which is “in here" … According to this view, Nature, in all her diversity, is “out there.” The task of the scientist is to observe the “out there" as objectively as possible. To observe something “objectively” means to see it as it would appear to an observer who has no prejudices about what he observes. The problem that went unnoticed for three centuries is that a person who carries such an attitude certainly is prejudiced. His prejudice is to be "objective," that is, to be without a preformed opinion. In fact, it is impossible to be without an opinion. An opinion is a point of view. The point of view that we can be without a point of view is a point of view. The decision itself to study one segment of reality instead of another is a subjective expression of the researcher who makes it. It affects his perceptions of reality, if nothing else. Since reality is what we are studying, the matter gets very sticky here. The new physics, quantum mechanics, tells us clearly that it is not possible to observe reality without changing it. If we observe a certain particle collision experiment, not only do we have no way of proving that the result would have been the same if we had not been watching it, all that we know indicates that it would not have been the same, because the result that we got was affected by the fact that we were looking for it. Some experiments show that light is wave-like. Other experiments show equally well that light is particle-like. If we want to demonstrate that light is a particle-like phenomenon or that light is a wave-like phenomenon, we only need to select the appropriate experiment. According to quantum mechanics there is no such thing as objectivity. We cannot eliminate ourselves from the picture. We are a part of nature, and when we study nature there is no way around the fact that nature is studying itself. Physics has become a branch of psychology, or perhaps the other way round. Carl Jung the Swiss psychologist, wrote “The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate, that is to say, when the individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner contradictions, the world must perforce act out the conflict and be torn into opposite halves.” Jung's friend, Nobel Prize-winning physicist, Wolfgang Pauli, put it this way: “From an inner center the psyche seems to move outward, in the sense of an extraversion into the physical world.” If these men are correct, then [quantum] physics is the study of the structure of consciousness.

|

|||

|

|