|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

return to "Government" main-page

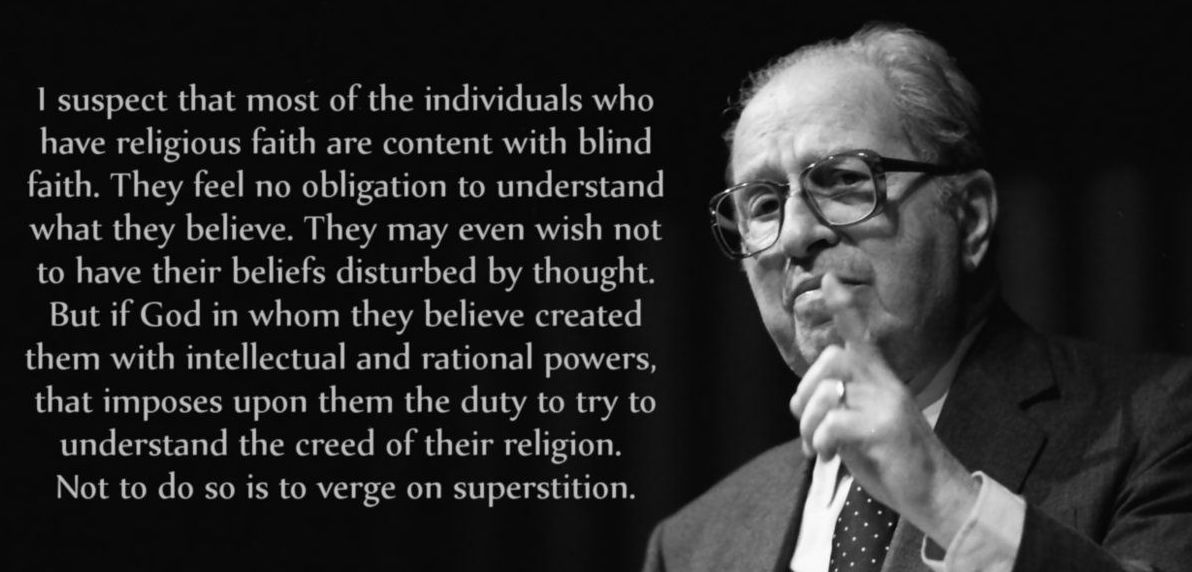

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler (1902 - 2001)

OF all the traditional names for forms of government, "democracy" has the liveliest currency today. Yet like all the others, it has a long history in the literature of political thought and a career of shifting meanings. How radically the various conceptions of democracy differ may be judged from the fact that, in one of its meanings, democracy flourished in the Greek city-states as early as the fifth century B.C.; while in another, democracy only began to exist in recent times or perhaps does not yet exist anywhere in the world. In our minds democracy is inseparably connected with constitutional government. We tend to think of despotism or dictatorship as its only opposites or enemies. That is how the major political issue of our day is understood. But as recently as the 18th century, some of the American constitutionalists prefer a republican form of government to democracy; and at other times, both ancient and modern, oligarchy or aristocracy, rather than monarchy or despotism, is the major alternative. "Democracy" has even stood for the lawless rule of the mob--either itself a kind of tyranny or the immediate precursor of tyranny. Throughout all these shifts in meaning and value, the word "democracy" preserves certain constant political connotations. Democracy exists, according to Montesquieu, "when the body of the people is possessed of the supreme power." As the root meaning of the word indicates, democracy is the "rule of the people." While there may be, and in fact often has been, a difference of opinion with respect to the meaning of "the people," this notion has been traditionally associated with the doctrine of popular sovereignty, which makes the political community as such the origin and basis of political authority. In the development of the democratic tradition, particularly in modern times, this has been accompanied by the elaboration of safeguards for the rights of man to assure that government actually functions for the people, and not merely for one group of them. Although they are essential parts of democracy, neither popular sovereignty nor the safeguarding of natural rights provides the specific characteristic of democracy, since both are compatible with any other just form of government. The specifically democratic element is apparent from the fact that throughout the many shifts of meaning which democracy has undergone, the common thread is the notion of political power in the hands of the many rather than the few or the one. Thus at the very beginning of democratic government, we find Pericles calling Athens a democracy because "its administration favours the many instead of the few." Close to our own day, Mill likewise holds that democracy is "the government of the whole people by the whole people" in which "the majority . . . will outvote and prevail." According as the many exercise legal power as citizens or merely actual power as a mob, democracy is aligned with or against constitutional government. The quantitative meaning of "many" can vary from more than the few to all or something approximating all, and with this variance the same constitution may be at one time regarded as oligarchical or aristocratic, and at another as democratic. The way in which the many who are citizens exercise their power--either directly or through representatives--occasions the 18th century distinction between a democracy and a republic, though this verbal ambiguity can be easily avoided by using the phrases "direct democracy" and "representative democracy," as was sometimes done by the writers of The Federalist and their American contemporaries. These last two points--the extension of the franchise and a system of representation--mark the chief differences between ancient and contemporary institutions of democracy. Today constitutional democracy tends to be representative, and the grant of citizenship under a democratic constitution tends toward universal suffrage. That is why we no longer contrast democracy and republic. That is why even the most democratic Greek constitutions may seem undemocratic--oligarchical or aristocratic--to us. To the extent that democracy, ancient or modern, is conceived as a lawful form of government, it has elements in common with other forms of lawful government which, for one reason or another, may not be democratic. The significance of these common elements--the principle of constitutionality and the status of citizenship--will be assumed here. They are discussed in the chapters on CONSTITUTION and CITIZEN. The general theory of the forms of government is treated in the chapter on GOVERNMENT, and the two forms most closely related to democracy, in the chapters on ARISTOCRACY and OLIGARCHY. THE EVALUATIONS of democracy are even more various than its meanings. It has been denounced as an extreme perversion of government. It has been grouped with other good, or other bad, forms of government, and accorded the faint praise of being called either the most tolerable of bad governments or the least efficient among acceptable forms. It has been held up as the political ideal, the only perfectly just state--that paragon of justice which has always been, whether recognized or not, the goal of political progress. Sometimes the same writer will express divergent views. Plato, for example, in the Statesman, claims that democracy has "a twofold meaning" according as it involves "ruling with law or without law." Finding it "in every respect weak and unable to do either any great good or any great evil," he concludes that it is "the worst of all lawful governments, and the best of all lawless ones." The rule of the many is least efficient for either good or evil. But in the Republic, he places democracy at only one remove from tyranny. On the ground that "the excessive increase of anything often causes a reaction in the opposite direction," tyranny is said to "arise naturally out of democracy, and the most aggravated form of tyranny and slavery out of the most extreme form of liberty." Similarly, Aristotle, in the Politics, calls democracy "the most tolerable" of the three perverted forms of government, in contrast to oligarchy, which he thinks is only "a little better" than tyranny, "the worst of governments." Yet he also notes that, among existing governments, "there are generally thought to be two principal forms--democracy and oligarchy .... and the rest are only variations of these." His own treatment conforms with this observation. He devotes the central portion of his Politics to the analysis of oligarchy and democracy. In his view they are equal and opposite in their injustice, and to him both seem capable of degenerating into despotism and tyranny. Among the political philosophers of modern times a certain uniformity of treatment seems to prevail in the context of otherwise divergent theories. Writers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, or Machiavelli, Montesquieu, and Kant differ in many and profound respects. But they classify the forms of government in much the same fashion. As Hobbes expresses it, "when the representative is one man, then is the commonwealth a monarchy; when an assembly of all that will come together, then it is a democracy, or popular commonwealth; when an assembly of a part only, then it is called an aristocracy." Though Hobbes favors monarchy and Montesquieu either aristocracy or democracy, these writers do not make the choice among the three traditional forms a significant expression of their own political theories. For them the more important choice is presented by other alternatives: for Hobbes between absolute and limited government; for Montesquieu and Locke, between government by law and despotism; for Rousseau and Kant, between a republic and a monarchy. The authors of The Federalist definitely show their preference for "popular government" as opposed to monarchy, aristocracy, or oligarchy. They usually refer to it as a "republic," by which they mean "a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people, and is administered by persons holding their offices during pleasure, for a limited period, or during good behavior." Alexander Hamilton and others involved in the American constitutional debates, as for example James Wilson, occasionally call this system a "representative democracy," but in The Federalist a republic is sharply differentiated from a democracy. The "great points of difference," however, turn out to be only "the delegation of the government (in a republic) to a small number of citizens elected by the rest," and the "greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country" to which a republic may extend. The difference, as already noted, is best expressed in the words "representative" and "direct" democracy. In Mill's Representative Government we find democracy identified with the ideal state. "The ideally best form of government," he writes, "is that in which the sovereignty, or supreme controlling power in the last resort, is vested in the entire aggregate of the community, every citizen not only having a voice in the exercise of that ultimate sovereignty, but being, at least occasionally, called on to take an actual part in the government, by the personal discharge of some public function, local or general." Though Mill recognizes the infirmities of democracy and though he readily concedes that it may not be the best government for all peoples under all circumstances, his argument for its superiority to all other forms of government remains substantially unqualified. IN MILL'S CONSTRUCTION of the democratic ideal as providing liberty and equality for all, the essential distinction from previous conceptions lies in the meaning of the word all. The republicans of the 18th century, in their doctrines of popular sovereignty and natural rights, understood citizenship in terms of equality of status and conceived liberty in terms of a man's having a voice in his own government. The ancients, seeing that men could be free and equal members of a political community only when they lived as citizens under the rule of law, recognized that the democratic constitution alone bestowed such equality upon all men not born slaves. But generally neither the ancients nor the 18th century republicans understood liberty and equality for all men to require the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of women from political subjection, or the eradication of all constitutional discriminations based on wealth, race, or previous condition of servitude. With Mill, all means every human person without regard to the accidents of birth or fortune. "There ought to be no pariahs in a full-grown and civilized nation," he writes, "no persons disqualified, except through their own default." Under the latter condition, he would withhold the franchise from infants, idiots, or criminals (including the criminally indigent), but with these exceptions he would make suffrage universal. He sums up his argument by claiming that "it is a personal injustice to withhold from any one, unless for the prevention of greater evils, the ordinary privilege of having his voice reckoned in the disposal of affairs in which he has the same interest as other people," and whoever "has no vote, and no prospect of obtaining it, will either be a permanent malcontent, or will feel as one whom the general affairs of society do not concern." But it should be added that for Mill the franchise is not merely a privilege or even a right; "it is," he says, "strictly a matter of duty." How the voter uses the ballot "has no more to do with his personal wishes than the verdict of a juryman .... He is bound to give it according to his best and most conscientious opinion of the public good. Whoever has any other idea of it is unfit to have the suffrage." The notion of universal suffrage raises at once the question of the economic conditions prerequisite to the perfection of political democracy. Can men exercise the political freedom of citizenship without freedom from economic dependence on the will of other men? Kant also argues that suffrage "presupposes the independence or self-sufficiency of the individual citizen." Because apprentices, servants, minors, women, and the like do not maintain themselves, each "according to his own industry, but as it is arranged by others," he claims that they are "mere subsidiaries of the Commonwealth and not active independent members of it," being "of necessity commanded and protected by others." For this reason, he concludes, they are "passive," not "active," citizens and can be rightfully deprived of the franchise. For political democracy to be realized in practice, more may be required than the abolition of poll taxes and other discriminations based on wealth: In the opinion of Karl Marx, the "battle for democracy" will not be won, nor even the "first step" taken towards it, until "the working class raises the proletariat to the position of ruling class." Quite apart from the merits of the revolutionary political philosophy which Marx erects, his views, and those of other social reformers of the 19th century, have made it a central issue that democracy be conceived in social and economic terms as well as political. Otherwise; they insist, what is called "democracy" will permit, and may even try to condone, social inequalities and economic injustices which vitiate political liberty. THERE IS ONE other condition of equality which the status of citizenship demands. This is equality of educational opportunity. According to Mill, it is "almost a self-evident axiom that the State should require and compel the education, up to a certain standard, of every human being who is born its citizen." All men may not be endowed with the same native abilities or talents, but all born with enough intelligence to become citizens deserve the sort of education which fits them for the life of political freedom. Quantitatively, this means a system of education as universal as the franchise; and as much for every individual as he can take, both in youth and adult life. Qualitatively, this means liberal education rather than vocational training, though in contemporary controversy this point is still disputed. The way in which it recognizes and discharges its educational responsibility tests the sincerity of modern democracy. No other form of government has a comparable burden, for no other calls all men to citizenship. In such a government, Montesquieu declares, "the whole power of education is required." Whereas despotism may be preserved by fear and a monarchy by a system of honor, a democracy depends on civic virtue. For where "government is intrusted to private citizens," it requires "love of the laws and of the country," and this, according to Montesquieu, is generally "conducive to purity of morals." Universal schooling by itself is not sufficient for this purpose. Democracy also needs what Mill calls the "school of public spirit." It is only by participating in the functions of government that men can become competent as citizens. By engaging in civic activities, a man "is made to feel himself one of the public, and whatever is for their benefit to be for his benefit." The "moral part of the instruction afforded by the participation of the private citizen, if even rarely, in public functions," results, according to Mill, in a man's being able "to weigh interests not his own; to be guided, in case of conflicting claims, by another rule than his private partialities; to apply, at every turn, principles and maxims which have for their reason of existence the common good." If national affairs cannot afford an opportunity for every citizen to take an active part in government, then that must be achieved through local government, and it is for this reason that Mill advocates the revitalization of the latter. THERE ARE OTHER problems peculiar to modern democracy. Because of the size of the territory and population of the national state, democratic government has necessarily become representative. Representation, according to The Federalist, becomes almost indispensable when the people is too large and too dispersed for assembly or for continuous, as well as direct, participation in national affairs. The pure democracy which the Federalists attribute to the Greek city-states may still be appropriate for local government of the town-meeting variety, but for the operations of federal or national government, the Federalists think the republican institutions of Rome a better model to follow. The Federalists have another reason for espousing representative government. The "mortal disease" of popular government, in their view, is the "violence of faction" which decides measures "not according to the rules of justice and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority." Believing the spirit of faction to be rooted in the nature of man in society, the American statesmen seek to cure its evil not by "removing its causes," but by "controlling its effects." The principle of representation, Madison claims, "promises the cure." Representation, by delegating government to a small number of citizens elected by the rest, is said "to refine and enlarge the public views by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country." From this it appears that representation provides a way of combining popular government with the aristocratic principle of government by the best men. The assumption that representation would normally secure the advantages of aristocratic government is not unmixed with oligarchical prejudices. If, as the Federalists frankly suppose, the best men are also likely to be men of breeding and property, representative government would safeguard the interests of the gentry, as well as the safety of the republic, against the demos--in Hamilton's words, "that great beast." Their concern with the evil of factions seems to be colored by the fear of the dominant faction in any democracy--the always more numerous poor. THE LEAVENING OF popular government by representative institutions in the formation of modern democracies raises the whole problem of the nature and function of representatives. To what extent does representation merely provide an instrument which the people employs to express its will in the process of self-government? To what extent is it a device whereby the great mass of the people select their betters to decide for them what is beyond their competence to decide for themselves? According to the way these questions are answered, the conception of the representative's function--especially in legislative matters--will vary from that of serving as the mere messenger of his constituents to that of acting independently, exercising his own judgment, and representing his constituents not in the sense of doing their bidding, but only in the sense that he has been chosen by them to decide what is to be done for the common good. At one extreme, the representative seems to be reduced to the ignominious role of a mouthpiece, a convenience required by the exigencies of time and space. Far from being a leader, or one of the best men, he need not even be a better man than his constituents. At the other extreme, it is not clear why the completely independent representative need even be popularly elected. In Edmund Burke's theory of virtual representation, occasioned by his argument against the extension of the franchise, even those who do not vote are adequately represented by men who have the welfare of the state at heart. They, no less than voting constituents, can expect the representative to consider what is for their interest, and to oppose their wishes if he thinks their local or special interest is inimical to the general welfare. Between these two extremes, Mill tries to find a middle course, in order to achieve the "two great requisites of government: responsibility to those for whose benefit political power ought to be, and always professes to be, employed; and jointly therewith to obtain, in the greatest measure possible, for the function of government the benefits of superior intellect, trained by long meditation and practical discipline to that special task." Accordingly, Mill would preserve some measure of independent judgment for the representative and make him both responsive and responsible to his constituents, yet without directing or restraining him by the checks of initiative, referendum, and recall. Mill's discussion of representation leaves few crucial questions unasked, though it may not provide clearly satisfactory answers to all of them. It goes beyond the nature and function of the representative to the problem of securing representation for minorities by the now familiar method of proportional voting. It is concerned with the details of electoral procedure--the nomination of candidates, public and secret balloting, plural voting--as well as the more general question of the differences among the executive, judicial, and legislative departments of government with respect to representation, especially the difference of representatives in the upper and lower houses of a bicameral legislature. Like the writers of The Federalist, Mill seeks a leaven for the democratic mass in the leadership of men of talent or training. He would qualify the common sense of the many by the expertness or wisdom of the few. The justice peculiar to the democratic constitution, Aristotle thinks, "arises out of the notion that those who are equal in any respect are equal in all respects; because men are equally free, they claim to be absolutely equal." It does not seem to him inconsistent with democratic justice that slaves, women, and resident aliens should be excluded from citizenship and public office. In the extreme form of Greek democracy, the qualifications for public office are no different from the qualifications for citizenship. Since they are equally eligible for almost every governmental post, the citizens can be chosen by lot rather than elected by vote. Rousseau agrees with Montesquieu's opinion of the Greek practice, that "election by lot is democratic in nature." He thinks it "would have few disadvantages in a real democracy, but," he adds, "I have already said that a real democracy is only an ideal." The justice peculiar to the oligarchical constitution is, according to Aristotle, "based on the notion that those who are unequal in one respect are in all respects unequal; being unequal, that is, in property, they suppose themselves to be unequal absolutely." The oligarchical constitution consequently does not grant citizenship or open public office to all the freeborn, but in varying degrees sets a substantial property qualification for both. Though he admits that the opposite claims of the oligarch and the democrat "have a kind of justice," Aristotle also points out the injustice of each. The democratic constitution, he thinks, does injustice to the rich by treating them as equal with the poor simply because both are freeborn, while the oligarchical constitution does injustice to the poor by failing to treat all free men, regardless of wealth, as equals. "Tried by an absolute standard," Aristotle goes on to say, "they are faulty, and, therefore, both parties, whenever their share in the government does not accord with their preconceived ideas, stir up a revolution." Plato, Thucydides, and Plutarch, as well as Aristotle, observe that this unstable situation permits demagogue or dynast to encourage lawless rule by the mob or by a coterie of the rich. Either paves the way to tyranny. To stabilize the state and to remove injustice, Aristotle proposes a mixed constitution which, by a number of different methods, "attempts to unite the freedom of the poor and the wealth of the rich." In this way he hopes to satisfy the two requirements of good government. "One is the actual obedience of citizens to the laws, the other is the goodness of the laws which they obey." By participating in the making of laws, all free men, the poor included, would be more inclined to obey them. But since the rich are also given a special function, there is, according to Aristotle, the possibility of also getting good laws passed, since "birth and education are commonly the accompaniments of wealth." To Aristotle the mixed constitution is perfectly just, and with an aristocratic aspect added to the blend, it approaches the ideal polity. Relative to certain circumstances it has "a greater right than any other form of government, except the true and ideal, to the name of the government of the best." Yet the true and the ideal, or what he sometimes calls the "divine form of government," seems to be monarchy for Aristotle, or rule by the one superior man; and in his own sketch of the best constitution at the end of the Politics--the best practicable, if not the ideal--Aristotle clearly opposes admitting all the laboring classes to citizenship. AS INDICATED IN the chapter on CONSTITUTION, Aristotle's mixed constitution should be distinguished from the mediaeval mixed regime, which was a combination of constitutional with non-constitutional or absolute government, rather than a mixture of different constitutional principles. The mixed regime--or "royal and political government"--seems to have come into being not as an attempt to reconcile conflicting principles of justice, but as the inevitable product of a decaying feudalism and a rising nationalism. Yet Aquinas claims that a mixed regime was established by divine law for the people of Israel; for it was "partly kingdom, since there is one at the head of all; partly aristocracy, in so far as a number of persons are set in authority; partly democracy, i.e., government by the people, in so far as the rulers can be chosen from the people, and the people have the right to choose their rulers." In such a system, the monarchical principle is blended with aristocratic and democratic elements to whatever extent the nobles and the commons play a part in the government. But neither group functions politically as citizens do under purely constitutional government. The question of constitutional justice can, however, be carried over from ancient to modern times. Modern democracy answers it differently, granting equality to all men on the basis of their being born human. It recognizes in wealth or breeding no basis for special political preferment or privilege. By these standards, the mixed constitution and even the most extreme form of Greek democracy must be regarded as oligarchical in character by a writer like Mill. Yet Mill, no less than Aristotle, would agree with Montesquieu's theory that the rightness of any form of government must be considered with reference to the "humor and disposition of the people in whose favor it is established." The constitution and laws, Montesquieu writes, "should be adapted in such a manner to the people for whom they are framed that it would be a great chance if those of one nation suit another." Mill makes the same point somewhat differently when he says, "the ideally best form of government . . .does not mean one which is practicable or eligible in all states of civilization." But although he is willing to consider the forms of government in relation to the historic conditions of a people, not simply by absolute standards, Mill differs sharply from Montesquieu and Aristotle in one very important respect. For him, as we have seen, representative democracy founded on universal suffrage is, absolutely speaking, the only truly just government--the only one perfectly suited to the nature of man. Peoples whose accidental circumstances temporarily justify less just or even unjust forms of government, such as oligarchy or despotism, must not be forever condemned to subjection or disfranchisement, but should rather be raised by education, experience, and economic reforms to a condition in which the ideal polity becomes appropriate for them. THE BASIC PROBLEMS of democratic government--seen from the point of view of those who either attack or defend it--remain constant despite the altered conception of democracy in various epochs. At all times, there is the question of leadership and the need for obtaining the political services of the best men without infringing on the political prerogatives of all men. The difference between the many and the few, between the equality of men as free or human and their individual inequality in virtue or talent, must always be given political recognition, if not by superiority in status, then by allocation of the technically difficult problems of statecraft to the expert or specially competent, with only certain broad general policies left to the determination of a majority vote. Jefferson and Mill alike hope that popular government may abolish privileged classes without losing the benefits of leadership by peculiarly gifted individuals. The realization of that hope, Jefferson writes Adams, depends on leaving "to the citizens the free election and separation of the aristoi from the pseudo-aristoi, of the wheat from the chaff." At all times there is the danger of tyranny by the majority and, under the threat of revolution, the rise of a demagogue who uses mob rule to establish a dictatorship. Hobbes phrases this peculiar susceptibility of democracy to the mischief of demagogues by saying of popular assemblies that they "are as subject to evil counsel, and to be seduced by orators, as a monarch by flatterers," with the result that democracy tends to degenerate into government by the most powerful orator. In his oration at the end of the first year of the Peloponnesian war, Pericles praises the democracy of Athens and at the same time celebrates the might of her empire. "It is only the Athenians," he says, "who, fearless of consequences, confer their benefits not from calculations of expediency, but in the confidence of liberality." But four years later, after the revolt of Mitylene, Cleon speaks in a different vein. Thucydides describes him as being "at that time by far the most powerful with the commons." He tells his fellow citizens of democratic Athens that he has "often before now been convinced that a democracy is incapable of empire," but "never more so than by your present change of mind in the matter of Mitylene." He urges them to return to their earlier decision to punish the Mitylenians, for, he says, if they reverse that decision they will be "giving way to the three failings most fatal to empire -pity, sentiment, and indulgence." Diodotus, who in this debate recommends a policy of leniency, does not do so in the "confidence of liberality" which Pericles had said was the attitude of a democratic state toward its dependencies. "The question is not of justice," Diodotus declares, "but how to make the Mitylenians useful to Athens .... We must not," he continues, "sit as strict judges of the offenders to our own prejudice, but rather see how by moderate chastisements we may be enabled to benefit in the future by the revenueproducing powers of our dependencies .... It is far more useful for the preservation of our empire," he concludes, "voluntarily to put up with injustice, than to put to death, however justly, those whom it is our interest to keep alive." Twelve years later, Alcibiades, no democrat himself, urges the Athenians to undertake the Sicilian expedition by saying, "we cannot fix the exact point at which our empire shall stop; we have reached a position in which we must not be content with retaining but must scheme to extend it, for, if we cease to rule others, we are in danger of being ruled ourselves." In the diplomatic skirmishes which precede the invasion of Sicily, Hermocrates of Syracuse tries to unite the Sicilian cities so that they may escape "disgraceful submission to an Athenian master." The Athenian ambassador, Euphemus, finds himself compelled to speak at first of "our empire and of the good right we have to it"; but he soon finds himself frankly confessing that "for tyrants and imperial cities nothing is unreasonable if expedient." The denouement of the Peloponnesian war, and especially of the Syracusan expedition, is the collapse of democracy, not through the loss of empire but as a result of the moral sacrifices involved in trying to maintain or increase it. Tacitus, commenting on the decay of republican institutions with the extension of Rome's conquests, underlines the same theme. It is still the same theme when the problems of British imperialism appear in Mill's discussion of how a democracy should govern its colonies or dependencies. The incompatibility of empire with democracy is one side of the picture of the democratic state in external affairs. The other side is the tension between democratic institutions and military power or policy--in the form of standing armies and warlike maneuvers. The inefficiency traditionally attributed to democracy under peaceful conditions does not, from all the evidences of history, seem to render democracy weak or pusillanimous in the face of aggression. The deeper peril for democracy seems to lie in the effect of war upon its institutions and on the morality of its people. As Hamilton writes in The Federalist: "The violent destruction of life and property incident to war, the continual effort and alarm attendant on a state of continual danger, will compel nations the most attached to liberty to resort for repose and security to institutions which have a tendency to destroy their civil and political rights. To be more safe, they at length become willing to run the risk of being less free."

|

||

|

|