|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

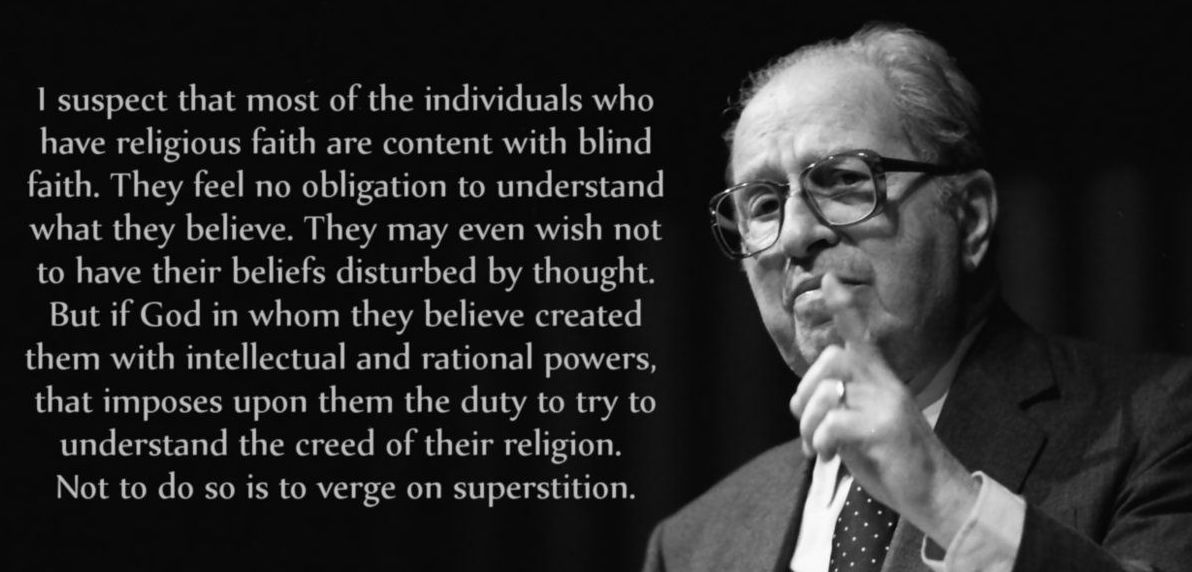

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler (1902 - 2001)

LIBERTY and law, liberty and justice, liberty and equality--the familiar connection of these terms breeds neglect of the meaning they confer upon one another through association. A few simple questions may help to restore the significance of these relationships. Are men free when their actions are regulated by law or coercion? Does liberty consist in doing whatever one pleases or whatever one has the power to do, or is one required by justice to abstain from injury to others? Do considerations of justice draw the line between liberty and license? Can there be liberty apart from equality and perhaps also fraternity?, Other questions immediately suggest themselves. Does not the rule of law secure liberty to the governed? Is not slavery the condition of those who are ruled tyrannically or lawlessly? Does it make a difference to freedom whether the law or the constitution is just? Or is that indifferent because government itself is the impediment to liberty? Does liberty increase as the scope of government dwindles and reach fullness only with anarchy or when men live in a state of nature? Yet are not some forms of government said to be fitting and some uncongenial to free men? Do all men have a right to freedom, or only some? Are some men by nature free and some slave? Does such a differentiation imply both equality and inequality in human nature with, as a consequence, equality and inequality in status or treatment? What implications for law, justice, and equality has the distinction between free societies and dependent or subject communities? As Tolstoy points out, the variety of questions which can be asked about liberty indicates the variety of subject matters or sciences in which the problems of freedom are differently raised. "What is sin, the conception of which arises from the consciousness of man's freedom? That is a question for theology . . . What is man's responsibility to society, the conception of which results from the conception of freedom? That is a question for jurisprudence . . . What is conscience and the perception of right and wrong in actions that follow from the consciousness of freedom? That is a question for ethics . . . How should the past life of nations and of humanity be regarded--as the result of the free, or as the result of the constrained, activity of man? That is a question for history." The great traditional issues of liberty seem to be stated by these questions. From the fact that most, perhaps all, of these questions elicit opposite answers from the great books, it might be supposed that there are as many basic issues as there are questions of this sort. But the answers to certain questions presuppose answers to others. Furthermore, the meaning of liberty or freedom or independence is not the same throughout the questions we have considered. Answers which appear to be inconsistent may not be so when the meanings involved in their formulation are distinguished. We must, therefore, find the roots of the several distinct doctrines of liberty in order to separate real issues from verbal conflicts. THE HISTORIANS report the age-old struggle on the part of men and of states for liberty or independence. History as a development of the spirit does not begin, according to Hegel, until this struggle first appears. "The History of the world," he writes, "is none other than the progress of the consciousness of Freedom," which does not reach its climax until freedom is universally achieved. But though freedom is its product, history, in Hegel's view, is not a work of freedom, but "involves an absolute necessity." Each stage of its development occurs inevitably. Other historians see man as free to work out his destiny, and look upon the great crises of civilization as turning points at which free men, that is, men having free will, exercise a free choice for better or for worse. "Whether we speak of the migration of the peoples and the incursions of the barbarians, or of the decrees of Napoleon III, or of someone's action an hour ago in choosing one direction out of several for his walk, we are unconscious of any contradiction," Tolstoy declares, between freedom and necessity. "Our conception of the degree of freedom," he goes on to say, "often varies according to differences in the point of view from which we regard the event, but every human action appears to us as a certain combination of freedom and inevitability. In every action we examine we see a certain measure of freedom and a certain measure of inevitability. And always the more freedom we see in any action the less inevitability do we perceive, and the more inevitability the less freedom." Accordingly, neither necessity which flows from the laws of matter or of spirit, nor overhanging and indomitable fate determines the direction of events. If the theologians say that nothing happens which God does not foresee, they also say that divine providence leaves the world full of contingencies and man a free agent to operate among them. "Though there is for God a certain order of all causes," it does not follow, Augustine says, that nothing depends "on the free exercise of our own wills, for our wills themselves are included in that order of causes which is certain to God, and is embraced by His foreknowledge, for human wills are also causes of human actions." These matters are further discussed in the chapters on FATE, HISTORY, and NECESSITY AND CONTINGENCY. The mention of them here suggests another meaning of liberty--that of free choice or free will--and with it issues other than those involved in the relation of the individual to the state or to his fellow men. Yet the metaphysical questions about liberty and necessity, or freedom and causality, and the theological questions about man's freedom under God, are not without bearing on the political problems of man's freedom in society, or his rights and powers. The fundamental doctrines of civil liberty certainly seem to differ according to the conception of natural freedom on which they are based. Freedom may be natural in the sense that free will is a part of human nature; or in the sense that freedom is a birthright, an innate and inalienable right. It may be natural in the sense in which freedom in a state of nature is distinguished from political liberty, or liberty under civil law and government. THE EFFORT TO clarify meanings requires us to look at the three words which we have used as if they were interchangeable--"liberty," "freedom," and "independence." For the most part, "liberty" and "freedom" are synonyms. Both words are used in English versions of the great books. Though authors or translators sometimes prefer one, sometimes the other, their preference does not seem to reflect a variation in meaning. In English the word "freedom" has a little greater range in that it permits the formation of the adjective "free." It is also adapted to speaking of freedom from certain restraints or undesirable conditions, as well as of freedom to act in accordance with desire or to exercise certain privileges. In consequence, the word "freedom" is more frequently employed in the discussion of free will. Though the traditional enumeration of civil liberties may use the phrasing "liberty of conscience or worship" as frequently as "freedom of conscience or worship," "freedom of speech" is more usual, and "freedom from fear or want or economic dependence" does not seem to have an alternative phrasing. The word "independence" has special connotations which make it equivalent to only part of the meaning of "freedom" or "liberty." Negatively, independence is a freedom from limitation or from being subject to determination by another. Positively, independence implies self-sufficiency and adequate power. When we speak of a man of independent means, we refer not only to his freedom from want or economic dependence on others, but also to his having sufficient wealth to suit his tastes or purposes. A moment's reflection will show that this is a relative matter. It is doubtful whether absolute economic independence is possible for men or even for nations. The real question here seems to be a metaphysical one. Can any finite thing be absolutely independent? The traditional answer is No. As appears in the chapter on INFINITY, only a being infinite in perfection and power--only the Supreme One of Plotinus, the uncreated God of Aquinas, or the self-caused God of Spinoza--has complete independence. God has the freedom of autonomy which cannot belong to finite things. There is, however, another sense of divine freedom which Aquinas affirms and both Plotinus and Spinoza deny. That is freedom of choice. "God does not act from freedom of will," Spinoza writes; yet God alone acts as a free cause, for God alone "exists from the necessity of his own nature and is determined to action by himself alone." The divine freedom consists in God's self-determination which, for Spinoza, does not exclude necessity. The opposite view is most clearly expressed in the Christian doctrine of creation. The created world does not follow necessarily from the divine nature. "Since the goodness of God is perfect," Aquinas writes, "and can exist without other things, inasmuch as no perfection can accrue to Him from them, it follows that for Him to will things other than Himself is not absolutely necessary." This issue of freedom or necessity with regard to God's will and action is more fully discussed in the chapters on WILL and WORLD. The metaphysical identification of independence with infinity does not carry over into the sphere of political freedom. Yet in one respect there is an analogy. The autonomous is that which is a law unto itself. It admits no superior authority. When in the tradition of political thought states are called "free and independent," their autonomy or sovereignty means that by virtue of which, in the words of the Declaration of Independence, "they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do." Free and independent states do not have infinite power. There is always the possibility of their being subjugated by another state and reduced to the condition of a dependency. But though their power is not infinite, they acknowledge no superior. To be a sovereign is to accept commands from no one. Since autonomy or sovereignty is incompatible with living under human law or government, the independence of sovereign princes or states must be an anarchic freedom--a freedom from law and government. This seems to be the view of Hobbes, Locke, Kant, and Hegel, all of whom refer to the anarchy of independent states or sovereign princes to explain what they mean by the "state of nature." Sovereigns are, in the words of Kant, "like lawless savages." Applying this conception to individual men, Hobbes and Locke define natural as opposed to civil liberty in terms of man's independence in a state of nature. In a state of nature man had a limited independence, since each man might be coerced by a superior force; but it was an absolute independence in the sense that he was subject to no human government or man-made law. THE NATURAL FREEDOM of man, according to Hobbes, is not free will. Since "every act of man's will, and every desire and inclination, proceed from some cause, and that from another cause, in a continual chain (whose first link is in the hand of God, the first of all causes), they proceed from necessity." Liberty is not of the will, but of the man, consisting in this: "that he finds no stop in doing what he has the will, desire, or inclination to do." The proper application of the word "free" is to bodies in motion, and the liberty it signifies when so applied is merely "the absence of external impediments." The natural right of every man is "the liberty each man has to use his own power . . . for the preservation of his own nature, that is to say, of his own life . . . and consequently of doing anything which in his own judgment and reason he shall conceive to be the aptest means thereunto." This liberty or natural right belongs to man only in a state of nature. When men leave the state of nature and enter the commonwealth, they surrender this natural liberty in exchange for a civil liberty which, according to Hobbes, consists in nothing more than their freedom to do what the law of the state does not prohibit, or to omit doing what the law does not command. Locke agrees that man's natural liberty is not the freedom of his will in choosing, but the freedom to do what he wills without constraint or impediment. He differs from Hobbes, however, in his conception of natural liberty because he differs in his conception of the state of nature. For Hobbes the state of nature is a state of war; the notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice, can have no place in it. "Where there is no common power, there is no law; where no law, no injustice." The liberty which sovereign states now have is the same as "that which every man should have if there were no civil laws, nor commonwealth at all. And the effects of it also are the same. For as amongst masterless men, there is perpetual war of every man against his neighbor . . . so in states and commonwealths not dependent on one another, every commonwealth has an absolute liberty to do what it shall judge . . . most conducing to its benefit." For Locke the state of nature is not a state of war, but a natural as opposed to a civil society, that is, a society in which men live together under natural rather than under civil law. Men who live in this condition are "in a state of perfect freedom to order their actions and dispose of their possessions as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature." This is a limited, not an absolute freedom; or, as Locke says, "though this be a state of liberty, yet it is not a state of license." The line between liberty and license is drawn by the precepts of the natural law. The difference, then, between natural and civil liberty lies in this. Natural liberty consists in being "free from any superior power on earth," or not being "under the will or legislative authority of man." Only the rules of natural law limit freedom of action. Civil liberty, or liberty under civil law, consists in being "under no other legislative power but that established by consent." It is a freedom for the individual to follow his own will in all matters not prescribed by the law of the state. IN THE ARGUMENTS for and against free will, one view regards free will as incompatible with the principle of causality, natural necessity, or God's omnipotence; the other conceives free choice as falling within the order of nature or causality and under God's providence. We shall not consider these alternatives in this chapter, since this issue is reserved for the chapter on WILL. Yet one thing is clear for the present consideration of political liberty. If the statement that men are born free means that it is a property of their rational natures to possess a free will, then they do not lose their innate freedom when they live in civil society. Government may interfere with a man's actions, but it cannot coerce his will. Government can go no further than to regulate the expression of man's freedom in external actions. Nor is the range of free will limited by law. As indicated in the chapter on LAW, any law--moral or civil, natural or positive--which directs human conduct can be violated. It leaves man free to disobey it and take the consequences. But if the rule is good or just, then the act which transgresses it must have the opposite quality. The freedom of a free will is therefore morally indifferent. It can be exercised to do either good or evil. We use our freedom properly, says Augustine, when we act virtuously; we misuse it when we choose to act viciously. "The will," he writes, "is then truly free, when it is not the slave of vices and sins." Those who conceive the natural moral law as stating the precepts of virtue or the commands of duty and who, in addition, regard every concrete act which proceeds from a free choice of the will as either good or bad--never indifferent--find that the distinction between liberty and license applies to every free act. The meaning of this distinction is the same as that between freedom properly used and freedom misused. Furthermore, since there is no good act which is not prescribed by the moral law, the whole of liberty, as opposed to license, consists in doing what that moral law commands. These considerations affect the problem of political liberty, especially on the question whether the spheres of law and liberty are separate, or even opposed. One view, as we have seen, is that the area of civil liberty lies outside the realm of acts regulated by law. To break the law may be criminal license, but to obey it is not to be free. The sphere of liberty increases as the scope or stringency of law diminishes. The opposite view does not regard freedom as freedom from law. "Freedom," Hegel maintains, "is nothing but the recognition and adoption of such universal substantial objects as Right and Law." All that matters in the relation between liberty and law is whether the law is just and whether a man is virtuous. If the law is just, then it does not compel a just man to do what he would not freely elect to do even if the law did not exist. Only the criminal is coerced or restrained by good laws. To say that such impediment to action destroys freedom would be to deny the distinction between liberty and license. Nevertheless, liberty can be abridged by law. That is precisely the problem of the good man living under unjust laws. If, as Montesquieu says, "liberty can consist only in the power of doing what we ought to will, and in not being constrained to do what we ought not to will," then governments and laws interfere with liberty when they command or prohibit acts contrary to the free choice of a good man. The conception of freedom as the condition of these who are rightly governed-who are commanded to do only what they would do anyway-seems to be analogically present in Spinoza's theory of human bondage and human freedom. It is there accompanied by a denial of the will's freedom of choice. According to Spinoza human action is causally determined by one of two factors in man's nature--the passions or reason. When man is governed by his passions, he is in "bondage, for a man under their control is not his own master, but is mastered by fortune, in whose power he is, so that he is often forced to follow the worse, although he sees the better before him." When man is governed by reason he is free, for he "does the will of no one but himself, and does those things only which he knows are of greatest importance in life, and which he therefore desires above all things." The man who acts under the influence of the passions acts in terms of inadequate ideas and in the shadow of error or ignorance. When reason rules, man acts with adequate knowledge and in the light of truth. So, too, in the theory of Augustine and Aquinas, the virtuous man is morally or spiritually free because human reason has triumphed in its conflict with the passions to influence the free judgment of his will. The rule of reason does not annul the will's freedom. Nor is the will less free when it is moved by the promptings of the passions. "A passion," writes Aquinas, "cannot draw or move the will directly." It does so indirectly, as, for example, "when those who are in some kind of passion do not easily turn their imagination away from the object of their affections." But though the will is not altered in its freedom by whether reason or emotion dominates, the situation is not the same with the human person as a whole. The theologians see him as a moral agent and a spiritual being who gains or loses freedom according as the will submits to the guidance of reason or follows the passions. On the supernatural level, the theologians teach that God's grace assists reason to conform human acts to the divine law, but also that grace does not abolish free choice on the part of the will. "The first freedom of the will," Augustine says, "which man received when he was created upright, consisted in an ability not to sin, but also in an ability to sin." So long as man lives on earth, he remains free to sin. But supernatural grace, added to nature, raises man to a higher level of spiritual freedom than he can ever achieve by the discipline of the acquired virtues. Still higher is the ultimate freedom of beatitude itself. Augustine calls this "the last freedom of will" which, by the gift of God, leaves man "not able to sin." It is worth noting that this ultimate liberty consists in freedom from choice or the need to choose, not in freedom from love or law. Man cannot be more free than when he succeeds, with God's help, in submitting himself through love to the rule of God. THE POLITICAL significance of these moral and theological doctrines of freedom would seem to be that man can be as free in civil society as in a state of nature. Whether in fact he is depends upon the justice of the laws which govern him, not upon their number or the matters with which they deal. He is, of course, not free to do whatever he pleases regardless of the well-being of other men or the welfare of the community, but that, in the moral conception of liberty, is not a loss of freedom. He loses freedom in society only when he is mistreated or misgoverned--when, being the equal of other men, he is not treated as their equal; or when, being capable of ruling himself, he is denied a voice in his own government. The meaning of tyranny and slavery seems to confirm this conception of political liberty. To be a slave is not merely to be ruled by another; it consists in being subject to the mastery of another, i.e., to be ruled as a means to that other's good and without any voice in one's own government. This implies, in contrast, that to be ruled as a free man is to be ruled for one's own good and with some degree of participation in the government under which one lives. According to Aristotle's doctrine of the natural slave--examined in the chapter on SLAVERY--some men do not have the nature of free men, and so should not be governed as free men. Men who are by nature slaves are not unjustly treated when they are enslaved. "It is better for them as for all inferiors," Aristotle maintains, "that they should be under the rule of a master." Though they do not in fact have the liberty of free men, they are not deprived thereby of any freedom which properly belongs to them, any more than a man who is justly imprisoned is deprived of a freedom which is no longer his by right. The root of this distinction between free men and slaves by nature lies in the supposition of a natural inequality. The principle of equality is also relevant to the injustice of tyranny and the difference between absolute and constitutional government. In the Republic Plato compares the tyrant to an owner of slaves. "The only difference," he writes, "is that the tyrant has more slaves" and enforces "the harshest and bitterest form of slavery." The tyrannical ruler enslaves those who are his equals by nature and who should be ruled as free men. Throughout the whole tradition of political thought the name of tyranny signifies the abolition of liberty. But absolute or despotic government is not uniformly regarded as the enemy of liberty. The issue concerning the legitimacy or justice of absolute government is examined in the chapters on MONARCHY and TYRANNY. But we can take it as generally agreed that the subjects of a despot, unlike the citizens of a republic, do not enjoy any measure of self-government. To the extent that political liberty consists in some degree of self-government, the subjects of absolute rule lack the sort of freedom possessed by citizens under constitutional government. For this reason the supremacy of law is frequently said to be the basic principle of political liberty. "Wherever law ends, tyranny begins," Locke writes. In going beyond the law, a ruler goes beyond the grant of authority vested in him by the consent of the people, which alone makes man "subject to the laws of any government." Furthermore, law for Locke is itself a principle of freedom. "In its true notion," he writes, it "is not so much the limitation as the direction of a free and intelligent agent to his proper interest, and prescribes no farther than is for the general good of those under that law. Could they be happier without it, the law, as a useless thing, would of itself vanish, and that ill deserves the name of confinement which hedges us in only from bogs and precipices. So that however it may be mistaken, the end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom." A constitution gives the ruled the status of citizenship and a share in their own government. It may also give them legal means with which to defend their liberties when officers of government invade their rights in violation of the constitution. According to Montesquieu, for whom political liberty exists only under government by law, never under despotism or the rule of men, the freedom of government itself demands "from the very nature of things that power should be a check to power." This is accomplished by a separation of powers. A system of checks and balances limits the power of each branch of the government and permits the law of the constitution to be applied by one department against another when its officials usurp powers not granted by the constitution or otherwise act unconstitutionally. Yet, unlike tyranny, absolute government has been defended. The ancients raise the question whether, if a truly superior or almost godlike man existed, it would not be proper for him to govern his inferiors in an absolute manner. "Mankind will not say that such a one is to be expelled and exiled," Aristotle writes; "on the other hand, he ought not to be a subject--that would be as if mankind should claim to rule over Zeus, dividing his offices among them. The only alternative," he concludes, "is that all should joyfully obey such a ruler, according to what seems to be the order of nature, and that men like him should be kings in their state for life." Those subject to his government would be free only in the sense that they would be ruled for their own good, perhaps better than they could rule themselves. But they would lose that portion of political freedom which consists in self-government. Faced with this alternative to constitutional government -- which Aristotle describes as the government of free men and equals -- what should be the choice of men who are by nature free? THE ANCIENT ANSWER IS not decisively in one direction. There are many passages in both Plato and Aristotle in which the absolute rule of a wise king (superior to his subjects as a father is to children, or a god to men) seems to be pictured as the political ideal. The fact that free men would be no freer than children in a well administered household does not seem to Plato and Aristotle to be a flaw in the picture. They do not seem to hold that the fullness of liberty is the primary measure of the goodness of government. On the contrary, justice is more important. As Aristotle suggests, it would be unjust for the superior man to be treated as an equal and given the status of one self-governing citizen among others. But he also points out that "democratic states have instituted ostracism" as a means of dealing with such superior men. "Equality is above all things their aim, and therefore they ostracized and banished from the city for a time those who seemed to predominate too much." Because it saves the superior man from injustice and leaves the rest free to practice self-government, "the argument for ostracism," Aristotle claims, "is based upon a kind of political justice," in that it preserves the balance within the state, and perhaps also because it leaves men free to practice self-government among themselves. Since the eighteenth century, a strong tendency in the opposite direction appears in the political thought of Locke, Montesquieu, Rousseau, Kant, the American constitutionalists, and J. S. Mill. Self-government is regarded as the essence of good government. It is certainly the mark of what the eighteenth century writers call "free government." Men who are born to be free, it is thought, cannot be satisfied with less civil liberty than this. "Freedom," says Kant, "is independence of the compulsory will of another; and in so far as it can co-exist with the freedom of all according to a universal law, it is the one sole, original inborn right belonging to every man in virtue of his humanity. There is, indeed, an innate equality belonging to every man which consists in his right to be independent of being bound by others to anything more than that to which he may also reciprocally bind them." The fundamental equality of men thus appears to be founded in their equal right to freedom; and that, for Kant at least, rests on the freedom of will with which all men are born. The criterion of the good society is the realization of freedom. Kant's conception of human society as a realm of ends, in which no free person should be degraded to the ignominy of being a means, expresses one aspect of political freedom. The other is found in his principle of the harmonization of individual wills which results in the freedom of each being consistent with the freedom of all. In institutional terms, republican government, founded on popular sovereignty and with a system of representation, is the political ideal precisely because it gives its citizens the dignity of free men and enables them to realize their freedom in self-government. Citizenship, according to Kant, has three inseparable attributes: "1. constitutional freedom, as the right of every citizen to have to obey no other law than that to which he has given his consent or approval; 2. civil equality, as the right of the citizen to recognize no one as a superior among the people in relation to himself, except in so far as such a one is as subject to his moral power to impose obligations, as that other has power to impose obligations upon him; and 3. political independence, as the right to owe his existence and continuance in society not to the arbitrary will of another, but to his own rights and powers as a member of the commonwealth, and, consequently, the possession of a civil personality, which cannot be represented by any other than himself." Kant leans heavily on Rousseau's conclusions with regard to political liberty. Rousseau, however, approaches the problem of freedom somewhat differently. "Man is born free," he begins, "and everywhere he is in chains." He next considers two questions. What makes government legitimate, "since no man has a natural authority over his fellow, and force creates no right"? Answering this first question in terms of a convention freely entered into, Rousseau then poses the second problem--how to form an association "in which each, while uniting himself with all, may still obey himself alone, and remain as free as before." This, he says, is "the fundamental problem of which the Social Contract provides the solution." The solution involves more than republican government, popular sovereignty, and a participation of the individual through voting and representation. It introduces the conception of the general will, through which alone the freedom of each individual is to be ultimately preserved. Like Kant's universal law of freedom, the general will ordains what each man would freely will for himself if he adequately conceived the conditions of his freedom. "In fact," says Rousseau, "each individual, as a man, may have a particular will contrary or dissimilar to the general will which he has as a citizen. His particular interest may speak to him quite differently from the common interest." Nevertheless, under conditions of majority rule, the members of the minority remain free even though they appear to be ruled against their particular wills. When a measure is submitted to the people, the question is "whether it is in conformity with the general will, which is their will. Each man, in giving his vote, states his opinion on that point; and the general will is found by counting votes. When, therefore, the opinion that is contrary to my own prevails, this proves neither more nor less than that I was mistaken, and that what I thought to be the general will was not so. If my particular opinion had carried the day, I should have achieved the opposite of what was my will; and it is in that case that I should not have been free. This presupposes, indeed, that all the qualities of the general will still reside in the majority; when they cease to do so, whatever side a man may take, liberty is no longer possible." J. S. MILL SEES THE same problem from the opposite side. Constitutional government and representative institutions are indispensable conditions of political liberty. Where Aristotle regards democracy as the type of constitution most favorable to freedom because it gives the equality of citizenship to all free-born men, Mill argues for universal suffrage to give equal freedom to all men, for all are born equal. But neither representative government nor democratic suffrage is sufficient to guarantee the liberty of the individual and his freedom of thought or action. Such phrases as "self-government" and "the power of the people over themselves" are deceptive. "The 'people' who exercise the power," Mill writes, "are not always the same people with those over whom it is exercised; and the 'self-government' spoken of is not the government of each by himself, but of each by all the rest. The will of the people, moreover, practically means the will of the most numerous or the most active part of the people; the majority, or those who succeed in making themselves accepted as the majority." To safeguard individual liberty from the tyranny of the majority, Mill proposes a single criterion for social control over the individual, whether by the physical force of law or the moral force of public opinion. "The sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection . . . The only part of the conduct of anyone, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign." Mill's conception of individual liberty at first appears to be negative--to be freedom from externally imposed regulations or coercions. Liberty increases as the sphere of government diminishes; and, for the sake of liberty, that government governs best which governs least, or governs no more than is necessary for the public safety. "There is a sphere of action," Mill writes, "in which society, as distinguished from the individual, has, if any, only an indirect interest; comprehending all that portion of a person's life and conduct which affects only himself, or if it also affects others, only with their free, voluntary, and undeceived consent and participation. When I say only himself," Mill continues, "I mean directly and in the first instance; for whatever affects himself, may affect others through himself . . . This, then, is the appropriate region of human liberty." But it is the positive aspect of freedom from governmental interference or social pressures on which Mill wishes to place emphasis. Freedom from government or social coercion is freedom for the maximum development of individuality--freedom to be as different from all others as one's personal inclinations, talents, and tastes dispose one and enable one to be. "It is desirable," Mill writes, "that in things which do not primarily concern others, individuality should assert itself." Liberty is undervalued as long as the free development of individuality is not regarded as one of the principal ingredients of human happiness and indispensable to the welfare of society. "The only freedom which deserves the name," Mill thinks, "is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it"; for, "in proportion to the development of his individuality, each person becomes more valuable to himself, and is therefore capable of being more valuable to others. There is a greater fullness of life about his own existence, and when there is more life in the units there is more in the mass which is composed of them." Mill's praise of liberty as an ultimate good, both for the individual and for the state, finds a clearly antiphonal voice in the tradition of the great books. Plato, in the Republic, advocates political regulation of the arts, where Mill, even more than Milton before him, argues against censorship or any control of the avenues of human expression. But the most striking opposition to Mill occurs in those passages in which Socrates deprecates the spirit of democracy because of its insatiable desire for freedom. That spirit, Socrates says, creates a city "full of freedom and frankness, in which a man may do and say what he likes . . . Where such freedom exists, the individual is clearly able to order for himself his own life as he pleases." The democratic state is described by Socrates as approaching anarchy through relaxation of the laws or through utter lawlessness. Under such circumstances there will be the greatest variety of individual differences. It will seem "the fairest of states, being like an embroidered robe which is spangled with every sort of flower." But it is a state in which liberty has been allowed to grow without limit at the expense of justice and order. It is "full of variety and disorder, and dispensing a sort of equality to equals and unequals alike."

|

||

|

|