|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

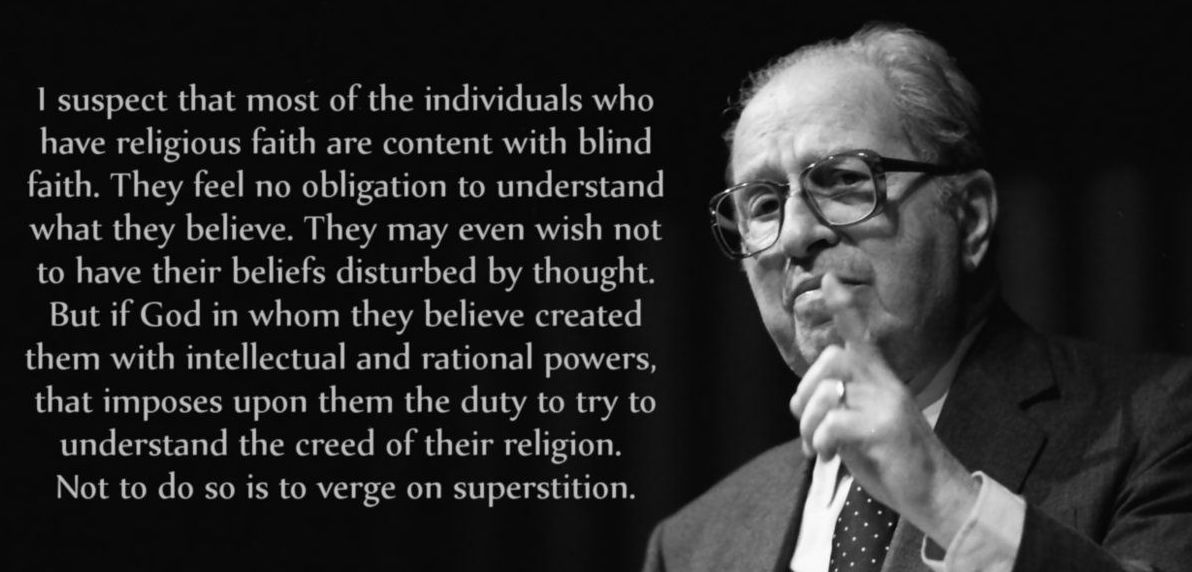

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler (1902 - 2001)

Truth, goodness, and beauty form a triad of terms... They have been called "transcendental" on the ground that everything which is is in some measure or manner subject to denomination as true or false, good or evil, beautiful or ugly. But they have also been assigned to special spheres of being or subject matter -- the true to thought and logic, the good to action and morals, the beautiful to enjoyment and aesthetics. They have been called "the three fundamental values" with the implication that the worth of anything can be judged by reference to these three standards... Truth, goodness, and beauty, singly and together, have been the focus of the age-old controversy concerning the absolute and the relative, the objective and the subjective, the universal and the individual. At certain times it has been thought that the distinction of true from false, good from evil, beautiful from ugly, has its basis and warranty in the very nature of things, and that a man's judgment of these matters is measured for its soundness or accuracy by its conformity to fact. At other times the opposite position has been dominant. One meaning of the ancient saying that man is the measure of all things applies particularly to the true, good, and beautiful. Man measures truth, goodness, and beauty by the effect things have upon him, according to what they seem to him to be... What seems ugly or false may also seem beautiful or true to different men or to the same man at different times... Beauty has been most frequently regarded as subjective, or relative to the individual judgment. The familiar maxim, de gustibus non disputandum... "Truth is disputable," writes Hume, "not taste ... No man reasons concerning another's beauty..." Beauty being simply a matter of individual taste [according to some], it could afford no basis for argument or reasoning -- no objective ground for settling differences of opinion. ... men have noted the great variety of traits ... which have been considered beautiful at different times and places. "We fancy its forms," Montaigne says of beauty, "according to our appetite and liking ..."

The degree to which [truth, goodness, and beauty] must be considered interdependently is determined by the extent to which each of the three terms requires the context of the other two for its definition and analysis.

But there have been ... many attempts... Usually notions of goodness, or correlative notions of desire and love, enter into the statement.

[Beauty, so defined, is a form of goodness.]

Hence, he continues, "beauty consists in due proportion, for the senses delight in things duly proportioned ... because the sense too is a sort of reason, as is every cognitive power."

To define beauty in terms of pleasure would seem to make it relative to the individual, for what gives pleasure ... to one man, may not to another.

... what in the object is the cause? Can the same object just as readily arouse displeasure in another individual...? Are these opposite reactions entirely the result of the way an individual feels? Aquinas appears to meet this difficulty by specifying certain objective elements of beauty:

Quite apart from individual reactions, objects may vary in the degree to which they possess such properties – traits which are capable of pleasing or displeasing their beholder. This does not mean that the individual reaction is invariably in accordance with the objective characteristics of the thing beheld.

Once again in the controversy concerning the objectivity or subjectivity of beauty, there seems to be

William James would seem to be indicating such a position when, in his discussion of aesthetic principles, he declares: "We are once and for all so made that when certain impressions come before our mind, one of them will seem to call for or repel the others as its companions." As an example, he cites the fact that "a note sounds good with its third and fifth." Such an aesthetic judgment certainly depends upon individual sensibility, and" James adds, "to a certain extent the principle of habit will explain [it]." But he also points out that "to explain all aesthetic judgments in this way would be absurd; for it is notorious how seldom natural experiences come up to our aesthetic demands:

KANT'S THEORY OF the beautiful, to take another conception, must also be understood in the general context of his theory of knowledge, and his analysis of such terms as good, pleasure, and desire. His definition, like that of Aquinas, calls an object beautiful if it satisfies the observer in a very special way--not merely pleasing his senses, or satisfying his desires, in the ways in which things good as means or ends fit a man's interests or purposes.

The aesthetic experience is for Kant also unique in that its judgment "is represented as universal, i.e. valid for every man," yet at the same time it is "incognizable by means of any universal concept." In other words, "all judgements of taste are singular judgements"; they are without concept in the sense that they do not apply to a class of objects. Nevertheless they have a certain universality and are not merely the formulation of a private judgment.

In saying that aesthetic judgments have subjective, not objective, universality, and in holding that the beautiful is the object of a necessary satisfaction, Kant also seems to take the middle position which recognizes the subjectivity of the aesthetic judgment without denying that beauty is somehow an intrinsic property of objects. With regard to its subjective character, Kant cites Hume to the effect that "although critics are able to reason more plausibly than cooks, they must still share the same fate."

The fact that the aesthetic judgment requires universal assent, even though the universal rule on which it is based cannot be formulated, does not, of course, preclude the failure of the object to win such assent from many individuals.

THE FOREGOING CONSIDERATIONS -- selective rather than exhaustive -- show the connection between definitions of beauty and the problem of aesthetic training. In the traditional discussion of the ends of education, there is the problem of how to cultivate good taste -- the ability to discriminate critically between the beautiful and the ugly.

The genuineness of the educational problem in the sphere of beauty seems, therefore, to depend upon

and which permits the educator to aim at a development of individual sensibilities in accordance with objective criteria of taste. THE FOREGOING CONSIDERATIONS also provide background for the problem of beauty in nature and in art. As indicated in the chapter on ART, the consideration of art in recent times tends to become restricted to the theory of the fine arts. So too the consideration of beauty has become more and more an analysis of excellence n poetry, music, painting, and sculpture. In consequence, the meaning of the word "aesthetic" has progressively narrowed, until now it refers almost exclusively to the appreciation of works of fine art, where before it connoted any experience of the beautiful, in the things of nature as well as in the works of man. The question is raised, then, whether natural beauty, or the perception of beauty in nature, involves the same elements and causes as beauty in art. Is the beauty of a flower or of a flowering field determined by the same factors as the beauty of a still life or a landscape painting? The affirmative answer seems to be assumed in a large part of the tradition. In his discussion of the beautiful in the Poetics, Aristotle explicitly applies the same standard to both nature and art. "To be beautiful," he writes, "a living creature, and every whole made up of parts, must not only present a certain order in its arrangement of parts, but also be of a certain magnitude." Aristotle's notion that art imitates nature indicates a further relation between the beautiful in art and nature. Unity, proportion, and clarity would then be elements common to beauty in its every occurrence, though these elements may be embodied differently in things which have a difference in their mode of being, as do natural and artificial things. With regard to the beauty of nature and of art, Kant tends to take the opposite position. He points out that "the mind cannot reflect on the beauty of nature without at the same time finding its interest engaged." Apart from any question of use that might be involved, he concludes that the "interest" aroused by the beautiful in nature is "akin to the moral," particularly from the fact that "nature . . . in her beautiful products displays herself as art, not as a mere matter of chance, but, as it were, designedly, according to a law-directed arrangement." The fact that natural things and works of art stand in a different relation to purpose or interest is for Kant an immediate indication that their beauty is different. Their susceptibility to disinterested enjoyment is not the same. Yet for Kant, as for his predecessors, nature provides the model or archetype which art follows, and he even speaks of art as an "imitation" of nature. The Kantian discussion of nature and art moves into another dimension when it considers the distinction between the beautiful and the sublime. We must look for the sublime, Kant says, "not ... in works of art . . . nor yet in things of nature, that in their very concept import a definite end, e.g. animals of a recognized natural order, but in rude nature merely as involving magnitude." In company with Longinus and Edmund Burke, Kant characterizes the sublime by reference to the limitations of human powers. Whereas the beautiful "consists in limitation," the sublime "immediately involves, or else by its presence provokes, a representation of limitlessness," which "may appear, indeed, in point of form to contravene the ends of our power of judgement, to be ill-adapted to our faculty of presentation, and to be, as it were, an outrage on the imagination." Made aware of his own weakness, man is dwarfed by nature's magnificence, but at that very moment he is also elevated by realizing his ability to appreciate that which is so much greater than himself. This dual mood signalizes man's experience of the sublime. Unlike the enjoyment of beauty, it is neither disinterested nor devoid of moral tone. TRUTH IS USUALLY connected with perception and thought, the good with desire and action. Both have been related to love and, in different ways, to pleasure and pain. All these terms naturally occur in the traditional discussion of beauty, partly by way of definition, but also partly in the course of considering the faculties engaged in the experience of beauty. Basic here is the question whether beauty is an object of love or desire. The meaning of any answer will, of course, vary with different conceptions of desire and love.

In this context, beauty seems to be more closely associated with a good that is loved than with a good desired. Love, moreover, is more akin to knowledge than is desire. The act of contemplation is sometimes understood as a union with the object through both knowledge and love. Here again the context of meaning favors the alignment of beauty with love, at least for theories which make beauty primarily an object of contemplation. In Plato and Plotinus, and on another level in the theologians, the two considerations -- of love and beauty -- fuse together inseparably. It is the "privilege of beauty," Plato thinks, to offer man the readiest access to the world of ideas. According to the myth in the Phaedrus the contemplation of beauty enables the soul to "grow wings." This experience, ultimately intellectual in its aim, is described by Plato as identical with love. The observer of beauty "is amazed when he sees anyone having a godlike face or form which is the expression of divine beauty; and at first a shudder runs through him, and again the old awe steals over him; then looking upon the face of his beloved as of a god, he reverence him, and if he were not afraid of being thought a downright madman, he would sacrifice to his beloved as to the image of a god." When the soul bathes herself "in the waters of beauty, her constraint is loosened, and she is refreshed, and has no more pangs and pains." This state of the soul enraptured by beauty, Plato goes on to say, "is by men called love." Sharply opposed to Plato's intellectualization of beauty is that conception which connects it with sensual pleasure and sexual attraction. When Darwin, for instance, considers sense of beauty, he confines his attention almost entirely to the colors and sounds used as "attractions of the opposite sex." Freud, likewise, while admitting that "psycho-analysis has less to say about beauty than about most things," claims that "its derivation from the realms of sexual sensation . . . seems certain." Such considerations may not remove beauty from the sphere of love, but, as the chapter LOVE makes clear, love has many meanings, and is of many sorts. The beautiful which is sexually attractive is the object of a love which is almost identical with desire -- sometimes with lust -- and certainly involves animal impulses and bodily pleasures. "The taste for the beautiful," writes Darwin, "at least as far as female beauty is concerned, is not of a special nature in the human mind." On the other hand, Darwin attributes to man alone an aesthetic faculty for the appreciation of beauty apart from love or sex. No other animal, he thinks, is "capable of admiring such scenes as the heavens at night, a beautiful landscape, or refined music;

For Freud, however, the appreciation of such beauties remains ultimately sexual in motivation, no matter how sublimated in effect. "The love of beauty," he says, "is the perfect example of a feeling with an inhibited aim. 'Beauty' and 'attraction' are first of all the attributes of a sexual object." The theme of beauty's relation to desire and love is connected with another basic theme -- the relation of beauty to sense and intellect, or to the realms of perception and thought. The two discussions naturally run parallel. The main question here concerns the existence of beauty in the order of purely intelligible objects, and its relation to the sensible beauty of material things. Plotinus, holding that beauty of every kind comes from a "form" or "reason," traces the "beauty which is in bodies," as well as that "which is in the soul" to its source in the "eternal intelligence." This "intelligible beauty" lies outside the range of desire even as it is beyond the reach of sense-perception. Only the admiration or the adoration of love is proper to it. THESE DISTINCTIONS in types of beauty -- natural and artificial, sensible and intelligible, even, perhaps, material and spiritual -- indicate the scope of the discussion, though not all writers on beauty deal with all its manifestations. Primarily concerned with other subjects, any of the great books make only an indirect contribution to the theory of beauty:

"The Divine Goodness," observes Dante, "which from Itself spurns all envy, burning in Itself so sparkles that It displays the eternal beauties." Some of the great books consider the various kinds of beauty, not so much with a view to classifying their variety, as in order to set forth the concordance of the grades of beauty with the grades of being, and with the levels of love and knowledge. The ladder of love in Plato's Symposium describes an ascent from lower to higher forms of beauty. "He who has been instructed thus far in the things of love," Diotima tells Socrates, "and who has learned to see beauty in due order and succession, when he comes toward the end will suddenly perceive a nature of wondrous beauty ... beauty absolute, separate, simple, and everlasting, which without diminution and without increase, or any change, is imparted to the ever-growing and perishing beauties of all other things. He who from these, ascending under the influence of true love, begins to perceive that beauty, is not far from the end."

For Plotinus the degrees of beauty correspond to degrees of emancipation from matter. "The more it goes towards matter ... the feebler beauty becomes." A thing is ugly only because, "not dominated by a form and reason, the matter has not been completely informed by the idea." If a thing could be completely "without reason and form," it would be "absolute ugliness." But whatever exists possesses form and reason to some extent and has some share of the effulgent beauty of the One, even as it has some share through emanation in its overflowing being -- the grades of beauty, as of being, signifying the remotion of each thing from its ultimate source. Even separated from a continuous scale of beauty, the extreme terms -- the beauty of God and the beauty of the least of finite things -- have similitude for a theologian like Aquinas.

An analogy is obviously implied. In this life and on the natural level, every experience of beauty -- in nature or art, in sensible things or in ideas -- occasions something like an act of vision, a moment of contemplation, of enjoyment detached from desire or action, and clear without the articulations of analysis or the demonstrations of reason.

|

||

|

|