|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Quantum Mechanics

return to "Quantum Mechanics" main-page

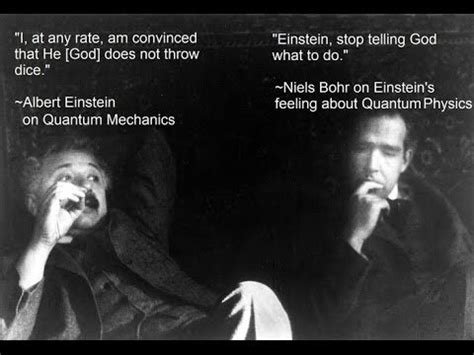

Jim Baggott: ‘The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One,’ wrote Albert Einstein in December 1926. ‘I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’ Einstein was responding to a letter from the German physicist Max Born. The heart of the new theory of quantum mechanics, Born had argued, beats randomly and uncertainly, as though suffering from arrhythmia. Whereas physics before the quantum had always been about doing this and getting that, the new quantum mechanics appeared to say that when we do this, we get that only with a certain probability. And in some circumstances we might get the other. Einstein was having none of it, and his insistence that God does not play dice with the Universe has echoed down the decades, as familiar and yet as elusive in its meaning as E = mc2. What did Einstein mean by it? And how did Einstein conceive of God? Hermann and Pauline Einstein were nonobservant Ashkenazi Jews. Despite his parents’ secularism, the nine-year-old Albert discovered and embraced Judaism with some considerable passion, and for a time he was a dutiful, observant Jew. Following Jewish custom, his parents would invite a poor scholar to share a meal with them each week, and from the impoverished medical student Max Talmud (later Talmey) the young and impressionable Einstein learned about mathematics and science. He consumed all 21 volumes of Aaron Bernstein’s joyful Popular Books on Natural Science (1880). Talmud then steered him in the direction of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781), from which he migrated to the philosophy of David Hume. From Hume, it was a relatively short step to the Austrian physicist Ernst Mach, whose stridently empiricist, seeing-is-believing brand of philosophy demanded a complete rejection of metaphysics, including notions of absolute space and time, and the existence of atoms. But this intellectual journey had mercilessly exposed the conflict between science and scripture. The now 12-year-old Einstein rebelled. He developed a deep aversion to the dogma of organised religion that would last for his lifetime, an aversion that extended to all forms of authoritarianism, including any kind of dogmatic atheism. This youthful, heavy diet of empiricist philosophy would serve Einstein well some 14 years later. Mach’s rejection of absolute space and time helped to shape Einstein’s special theory of relativity (including the iconic equation E = mc2), which he formulated in 1905 while working as a ‘technical expert, third class’ at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. Ten years later, Einstein would complete the transformation of our understanding of space and time with the formulation of his general theory of relativity, in which the force of gravity is replaced by curved spacetime. But as he grew older (and wiser), he came to reject Mach’s aggressive empiricism, and once declared that ‘Mach was as good at mechanics as he was wretched at philosophy.’ Over time, Einstein evolved a much more realist position. He preferred to accept the content of a scientific theory realistically, as a contingently ‘true’ representation of an objective physical reality. And, although he wanted no part of religion, the belief in God that he had carried with him from his brief flirtation with Judaism became the foundation on which he constructed his philosophy. When asked about the basis for his realist stance, he explained: ‘I have no better expression than the term “religious” for this trust in the rational character of reality and in its being accessible, at least to some extent, to human reason.’ But Einstein’s was a God of philosophy, not religion. When asked many years later whether he believed in God, he replied: ‘I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the lawful harmony of all that exists, but not in a God who concerns himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.’ Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz, had conceived of God as identical with nature. For this, he was considered a dangerous heretic, and was excommunicated from the Jewish community in Amsterdam. Einstein’s God is infinitely superior but impersonal and intangible, subtle but not malicious. He is also firmly determinist. As far as Einstein was concerned, God’s ‘lawful harmony’ is established throughout the cosmos by strict adherence to the physical principles of cause and effect. Thus, there is no room in Einstein’s philosophy for free will: ‘Everything is determined, the beginning as well as the end, by forces over which we have no control … we all dance to a mysterious tune, intoned in the distance by an invisible player.’ The special and general theories of relativity provided a radical new way of conceiving of space and time and their active interactions with matter and energy. These theories are entirely consistent with the ‘lawful harmony’ established by Einstein’s God. But the new theory of quantum mechanics, which Einstein had also helped to found in 1905, was telling a different story. Quantum mechanics is about interactions involving matter and radiation, at the scale of atoms and molecules, set against a passive background of space and time. Earlier in 1926, the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger had radically transformed the theory by formulating it in terms of rather obscure ‘wavefunctions’. Schrödinger himself preferred to interpret these realistically, as descriptive of ‘matter waves’. But a consensus was growing, strongly promoted by the Danish physicist Niels Bohr and the German physicist Werner Heisenberg, that the new quantum representation shouldn’t be taken too literally. In essence, Bohr and Heisenberg argued that science had finally caught up with the conceptual problems involved in the description of reality that philosophers had been warning of for centuries. Bohr is quoted as saying: ‘There is no quantum world. There is only an abstract quantum physical description. It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how nature is. Physics concerns what we can say about nature.’ This vaguely positivist statement was echoed by Heisenberg: ‘[W]e have to remember that what we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning.’ Their broadly antirealist ‘Copenhagen interpretation’ – denying that the wavefunction represents the real physical state of a quantum system – quickly became the dominant way of thinking about quantum mechanics. More recent variations of such antirealist interpretations suggest that the wavefunction is simply a way of ‘coding’ our experience, or our subjective beliefs derived from our experience of the physics, allowing us to use what we’ve learned in the past to predict the future. But this was utterly inconsistent with Einstein’s philosophy. Einstein could not accept an interpretation in which the principal object of the representation – the wavefunction – is not ‘real’. He could not accept that his God would allow the ‘lawful harmony’ to unravel so completely at the atomic scale, bringing lawless indeterminism and uncertainty, with effects that can’t be entirely and unambiguously predicted from their causes. The stage was thus set for one of the most remarkable debates in the entire history of science, as Bohr and Einstein went head-to-head on the interpretation of quantum mechanics. It was a clash of two philosophies, two conflicting sets of metaphysical preconceptions about the nature of reality and what we might expect from a scientific representation of this. The debate began in 1927, and although the protagonists are no longer with us, the debate is still very much alive. And unresolved. I don’t think Einstein would have been particularly surprised by this. In February 1954, just 14 months before he died, he wrote in a letter to the American physicist David Bohm: ‘If God created the world, his primary concern was certainly not to make its understanding easy for us.’

from https://www.stmarys.ac.uk/news/2014/09/physics-beyond-god-play-dice-einstein-mean/ Albert Einstein is one of the greatest and certainly best known physicists. If you ask anyone to name a physicist the most common answer you will receive is “Einstein”. Einstein is also famous for his quotations. Among the many Einstein’s quotations one is particularly popular among the general public: “God does not play dice”. But what did Einstein mean by this? The quotation says, “Quantum theory yields much, but it hardly brings us close to the Old One’s secrets. I, in any case, am convinced He does not play dice with the universe.” It was addressed by Einstein to Max Born (one of the fathers of Quantum Mechanics) in a letter that he wrote to Born in 1926. The “Old one” and “He” Einstein refers to is God. The fame of this quotation stems from two sources: 1) Einstein’s disagreement with the fundamental concept of Quantum Mechanics that at the quantum (i.e. atomic) level nature and the universe are totally random, namely events happen by mere chance; 2) Einstein’s views about religion and God. At first sight these two sources seem to be completely uncorrelated, not to say opposite, and many scientists and members of the general public will agree with this, but some other scientists and perhaps a portion of the general public will probably see a correlation between these two realms: science and religion. Let us look at these two sources individually. Quantum Physics; we keep hearing these two words every now and again but what Quantum Physics is and how does it enter in the equation of our daily lives? Quantum Physics is one of the pillars of modern physics and underpins most of the modern technology that makes our lives comfortable and enjoyable. For example, Quantum Physics is at the heart of transistors, little devices that make our mobile phones, laptops, tablets etc. work... But if Quantum Physics is such a useful theory why did Einstein disagree with it? After all, Quantum Physics cannot predict events precisely (like the statistical theories that can be used to predict which number will come out when we throw dice). Quantum Physics is based on the notorious 'Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle', which states that one cannot simultaneously measure the position and the momentum... Nothing can be certain according to Quantum Physics. We can only predict how probable an event is to happen (like how many probabilities are there for six to come out when we throw dice). It was this uncertainty that Einstein disagreed with. In his opinion, every event and the physical properties of each individual particle can, and must be measured with high precision. Quantum physics does not allow for that; it tells you how probable it is for a system of particles to behave in a certain way but it will never tell you how each individual particle belonging to that system will behave. Einstein could not accept this level of randomness and uncertainty in nature and the universe and he expressed his opinion in the sentence “God does not play dice”. Here we come to the second source: Einstein’s view about religion. Much has been written and speculated about this point. Some people are convinced that Einstein was an atheist and others believe that Einstein was religious but not in the orthodox way. Einstein wrote a lot about science and religion, so why don’t we ask him? Einstein was Jewish by birth and after a period of deep religiosity in his youth he did not practice Judaism. However, Einstein was not an atheist as he said himself in an interview in 1929. Einstein had his personal views about religion and he believed in what he called “cosmic religion” where God’s presence was evident in the order and rationality of nature and the universe in all its aspects and expressions. Chaos and randomness are, therefore, not part of nature (“God does not play dice”). According to Einstein, “cosmic religious feeling is the strongest and noblest motive for scientific research”. In his opinion, the goal of a scientist should be to try to begin to understand the universe. Einstein had a deep feeling of awe in front of nature and the universe and he believed that “strenuous intellectual work and the study of God’s Nature are the angels that will lead me through all the troubles of this life with consolation, strength, and uncompromising rigor” (letter to Pauline Winteler, 1897).

|

||

|

|