|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Kant The Critique of Pure Reason Professor Victor Gijsbers: The Problem of Knowledge:

return to 'critique of pure reason' contents page

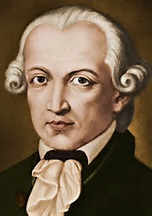

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

A rough transcript of Professor Victor Gijsbers' lecture:

Let’s start with the following question: What is objective knowledge? – it is knowledge about an object. Now, here is a standard answer to this question: We have objective knowledge when, in a sense, we have a copy of that object in our mind, when our mind is the mirror of nature. The major epistemological question facing modern philosophy is, how can we know if the mind is a good mirror, and not a clouded and distorted mirror? So, if to know is to mirror, then it’s hard to see how the problem of reality can be solved. And now here is Kant who is telling us that to know is definitely not to mirror. And it is pretty easy to see why he would want to say that. Even a good mirror does not have knowledge. So, why doesn’t a mirror have knowledge? We could say, it’s not conscious, it doesn’t think, - yes, these are the right answers, but why are they the right answers? Why would these be necessary preconditions of knowledge if to know is merely to mirror? Now, even if we were to add the element of consciousness to a mirror, even then it would seem that this is not enough, that, just to have a copy or a picture of reality in your mind is not sufficient to have knowledge. The Empiricists, such as Hume, fall into this error, when they say that to believe something is just to have a vivid picture of it in your mind and this would be knowledge for them. But this is not really what knowledge is. In order to know something we have to take up what is given in sense perception, in experience, and then we have to compare it and put it into a whole, where it has to fit, and if it doesn’t fit then we have to make a negative judgment about it and discard it. In other words, when we take in sense perceptions, these do not become knowledge unless these enter a process that has to do with fitting the perceptions into a larger whole. Here’s an example. Suppose that I glance at the side of the room and I see a cow! a real cow in my study! But then I glance again, but now I see nothing, no cow. I run to the door, to the corridor, but I see no cow. And so I come to the judgment that there was no cow, even though I thought I saw a cow. The right judgment is that I didn’t see a cow. How do I know that this is the right judgment? I know this by comparing my perception of the cow in my study with my entire existing knowledge base concerning where cows are likely to be, the nature of cows, whether they can suddenly disappear, etc. We enter this process of “fitting in” perceptions all the time, every day. We are active in this process. We’re not taking in every perception and ranking it as valid or equal with all others but, instead, we sift and sort and discard, and we do this all the time. Once we see how this works in our minds, we understand that knowledge is way more than simply being a mirror of what’s out there, a copy of reality. And when we understand this, we can begin to understand Kant. There is a statement in “Introduction B” to look at now: For where would experience itself get its certainty if all rules in accordance with which it proceeds were themselves in turn always empirical, thus contingent? And if you have the idea that knowledge is just a mirror of objects out there, then this statement is very mysterious, indeed. For, why would we need “rules” for experience, and why does Kant say that experience “proceeds” in accordance with these rules? But what he says here does make sense if we do something with the sense perceptions that come to us. Kant says we need a priori principles of cognition [principles in place even before we have sense perceptions] – why? Experience could never achieve “certainty” if there were no underlying rules in place before the process even begins; that is, if these rules were merely “contingent,” sometimes applying and sometimes not. We need rules to process experience, whether to accept the perceptions as valid or only a dream. Now, one of the key words for Kant, that we’re going to see quite a lot, having to do with understanding our perceptions, is “spontaneity.” What does this mean? Well, at very least it means that it is active. It is doing something. It is determining itself. It is not just passive. Kant has “spontaneity” on the one hand and “receptivity” on the other. Sense impression is receptivity, we get this from the outside – but then we do something with these impressions, and this speaks to “spontaneity.” And with all this, it’s not just random, not just a process – but an activity. A process is something that happens in time, maybe according to certain laws, working like a mechanism. This is what Hume is giving us. And Kant thinks that Hume has not really grasped the spontaneity of the mind. Kant has good reason to use the word “rule.” A rule is something you have to apply, you have to reason with the rule as basis. The rule has an implicit goal. This is the central difference between process and activity. If something is just happening, like a ball rolling down a plane, that’s a process. If I am making this video, that’s a goal, that’s an activity. I want to teach certain things. The mind’s knowledge acquisition, human cognition, too, is an activity, is pointed toward a goal, it’s teleological. And it’s goal is a unified grasp of reality. It is an activity of unification. We are given all these things [rules for the mind] and we use them to do something with sense perceptions, we’re going to unify them, we’re going to fit them, compare them, we’re going to try to generalize, to expand, expand, expand our knowledge, to fill up the gaps of understanding. Knowledge is an activity that seeks for a goal of total understanding the world and life. Knowledge, we could say, has a kind of life, it is a living activity, always moving, from one place to another – from relative ignorance to relative knowledge. It sees itself, knows itself, as always growing toward more knowledge. And therefore, human cognition is always self-conscious of its finitude, of the fact that it doesn’t know everything, that there are these gaps in understanding, and it’s always pushing at these limits to make itself more and better – even though it has no assurance of every arriving at that goal. This is the basic picture of knowledge which, I think, Kant is working with. This pursuit of knowledge has both internal and external factors; both spontaneity and receptivity. But we ourselves, as subject, become the great unifier of the objects, of all the sense impressions coming to us. We have to understand the world in terms of this pursuit of knowledge. In summary, to know is not to mirror, to know is to unify, and the subject is the unifier, the object is to be unified. We start our endeavor here by talking about the activity of knowing – that’s where we have to start. We don’t start with an idea of reality as independent from us. And so, this solves the problem of reality. There are standards of correctness. We have to get things right. This is not a bad subjectivism where you can believe whatever you like and call it truth. There are standards of correctness, and these are internal to the knowledge acquisition endeavor. To be right is not to have mirrored, in our minds, a reality that is independent of us, but – to be right is to have achieved successful unification. Why did philosophers before Kant fall into the notion that knowledge needs to be a kind of mirroring process? When we look at the object of knowledge, it is, sort of, this thing which has to be fitted into a picture of the world. And so, when we start thinking about the problem of reality, the relation between human knowledge and the world, what we tend to do is, we take human knowledge as our object – there’s the object of the world – one object – but then there’s human knowledge – which can be seen as another object, an object of our thinking – and now we try to fit both of them into the web of our knowledge, and by doing so we are, sort of, taking up the subject as an object – we’re trying to understand the subject in the kind of terms that we usually try to understand objects, and so knowledge is going to appear as something like a picture, rather than as something like a goal-directed activity. And so, we needed Kant to make this error, and its resolution, as the real starting point of philosophy and drawing out its consequences. And that would be the Copernican Revolution.

|

||

|

|