|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Kant The Critique of Pure Reason glossary

return to 'critique of pure reason' contents page

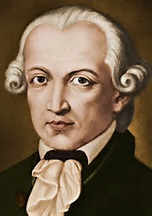

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

"But the Critique is not merely defective in clearness or

a priori Robert Paul Wolff: knowledge is said to be a priori if it is prior to experience, not in the sense of coming before we ever have any experience, but in the sense of logically prior to experience, logically independent of experience; a priori and a posteriori are adverbs, they qualify verbs, in particular, ‘to know'

absolute Howard Caygill: 'Absolute' is the past participle of absolvere, 'to absolve, to acquit, to free from debt'. The term can be used adjectivally or substantively: it either qualifies something as free from any relation, condition or limitation, or designates that which is thus free. The philosophical use of the term is modern, appearing first in Spinoza where it echoes political discussions of 'absolute sovereignty' and theological discussions of God as absolute. Spinoza's use of the term is adjectival, as in 'absolute certainty', 'absolute motion', the 'absolute dominion of the mind over the affects' (see Deleuze, 1988, p. 44). Even God is only adjectivally qualified as absolute, and is defined in Ethics I def. 6 (1677) as 'a being absolutely infinite' (Spinoza, 1985, p. 409; see also pp. 237, 264, 595). Kant too uses the term adjectivally, and usually in opposition to 'relative' and 'comparative'. His earliest recorded use appears in the distinction between absolute and relative position in OPA. In CPR he devotes over two pages to clarifying 'an expression with which we cannot dispense, and which yet, owing to an ambiguity that attaches to it through longstanding misuse, we also cannot with safety employ.' (A 324/B 380). The ambiguity involves two adjectival senses of absolute. The first refers to internal possibility - 'that which is in itself possible', i.e., the bare possibility or 'the least that can be said of an object'; the second indicates 'that something is valid in all respects, without limitation, e.g., absolute despotism, and in this sense the absolutely possible would mean what is in every relation (in all respects) possible - which is the most which can be said of the possibility of a thing.' (A 324/B 381). Kant opts for the second, broader sense of absolute, but warns that it must be used circumspectly. Throughout the critical philosophy Kant criticizes pure reason's illegitimate claims to know the absolute. The cosmological ideas may claim to represent 'absolute completeness' in the composition, division, origination and dependence of appearances (A 415/B 443), but are shown upon critical scrutiny to yield the antinomies. Kant on the whole refrains from giving the absolute any substantive content; he does not use the term to qualify either the thing-in-itself or the categorical imperative. However, he does refer in passing to 'absolute self-activity (freedom)' (A 418/B446), parenthetically suggesting a substantive identification of the absolute with freedom.

immanent Howard Caygill: "immanent principles 'whose application is confined entirely within the limits of possible experience’ [as opposed to the 'transcendent']" Robert Paul Wolff: "lying within experience" rather than "transcendent," which is "beyond the limits of experience"

transcendent Howard Caygill: Kant distinguishes between the transcendent and the transcendental. Transcendent is the term used to describe those principles which 'profess to pass beyond' the limits of experience, as opposed to immanent principles 'whose application is confined entirely within the limits of possible experience’. Transcendent principles 'which recognise no limits' are to be distinguished from the transcendental employment of immanent principles beyond their proper limits. Such principles include the psychological, cosmological and theological ideas discussed in the 'Transcendental Dialectic'.

transcendental Robert Paul Wolff: roughly has the meaning what today we would call epistemological, Kant means "having to do with the grounds and nature of human knowledge"; sometimes Kant forgets his own terminology and mistakenly switches transcendent for transcendental, back and forth, but the context tells us what he means. Howard Caygill: In medieval philosophy the transcendentals denoted the extra-categorical attributes of beings: unity, truth, goodness, beauty (and, in some classifications, thing and something). For Kant, a trace of this usage survives in his use of transcendental as a form of knowledge, not of objects themselves but of the ways in which we are able to know them, namely the conditions of possible experience. Thus he 'entitle[s] transcendental all knowledge which is occupied not so much with objects as with the mode of our knowledge of objects in so far as this mode of knowledge is to be possible a priori'. The system of the concepts which constitute a priori knowledge may be described as transcendental philosophy, for which the critique of pure reason is variously described as a propaedeutic, canon or architectonic. The term transcendental is used ubiquitously to qualify nouns such as logic, aesthetic, unity of apperception, faculties illusion; in each case it signals that the noun it qualifies is being considered in terms of its conditions of possibility. The precise meaning of the term transcendental shifts throughout CPR, but its semantic parameters may be indicated by showing the ways in which Kant distinguishes it from its contraries. The transcendental is distinguished from the empirical, and aligned with the a priori in so far as the a priori involves a reference to the mode of knowledge; it 'signifies such knowledge as concerns the a priori possibility of knowledge, or its a priori employment'. The distinction of transcendental and empirical thus involves the metacritique of knowledge and its a priori sources. Kant regards the psychological account of knowledge as a branch of the empirical, and thus in turn distinguishes it from transcendental knowledge. The transcendental is also distinguished from the metaphysical and the logical. A metaphysical exposition of space, for example, is one which represents what belongs to a concept given a priori, while a transcendental exposition explains a concept 'as a principle from which the possibility of other a priori synthetic knowledge can be understood'. A transcendental distinction of the sensible and the intelligible differs from a logical distinction - which involves 'their form as being either clear or confused' - by its concern with 'origin and content'. Finally, Kant distinguishes between transcendental and transcendent, contrasting the transcendent principles which 'incite us to tear down all those boundary-fences and seize possession of an entirely new domain which recognises no limits of demarcation' from the transcendental 'misemployment' of the categories, which extends their application beyond the limits of possible experience, and 'which is merely an error of the faculty of judgement'. Prof. V. Gijsbers: Kant here, in the Introduction B, defines “transcendental.” It refers not to objects, there is no transcendental object, but when we do transcendental philosophy we are thinking about how we can have knowledge of objects a priori, it’s about how we think, it’s a reflection on our relation to the world, and to knowledge. The word “transcendent” for Kant is much different and means “beyond the bounds of knowledge” or beyond the bounds of experience.” So, transcendent knowledge would be, maybe, knowledge of God, for example. “Transcendent philosophy” would go beyond the bounds of experience. Kant thinks transcendent philosophy is impossible, and that we should not strive for it. Stephen Palmquist: one of Kant's four main perspectives, aiming to establish a kind of knowledge which is both synthetic and a priori. It is a special type of philosophical knowledge, concerned with the necessary conditions for the possibility of experience. However, Kant believes all knowing subjects assume certain transcendental truths, whether or not they are aware of it. Transcendental knowledge defines the boundary between empirical knowledge and speculation about the transcendent realm. 'Every event has a cause' is a typical transcendental statement. (Cf. empirical.)

this page is under construction

|

||

|

|