|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Kant The Critique of Pure Reason Preface, Second Edition (B) 1787

return to 'critique of pure reason' contents page

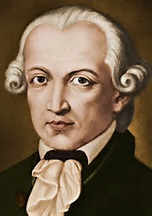

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

auxiliary sources for 'The Critique' VG: Professor Victor Gijsbers, Netherlands, youtube lectures DR: Professor Daniel Robinson, Oxford, youtube lectures RPW: Prof. Robert Paul Wolff, youtube lectures MJT: translation, Mieklejohn PGT: translation, Paul Guyer MMT: translation, Max Muller: "[His] main merit, as he has very justly claimed, is his greater accuracy in rendering passages in which a specially exact appreciation of the niceties of German idiom happens to be important for the sense." NST NST: translation, N.K. Smith PRTC: translation-commentary, P.M. Rudisill NSC: commentary, N.K. Smith SGC: commentary, Sebastian Gardner SP: glossary, Stephen Palmquist LT: glossary, Lucas Thorpe

*********************************************

The Critique of Pure Reason Preface to the second edition Whether or not the treatment of the cognitions belonging to the concern If after many preliminaries and preparations are made, a science gets stuck as soon as it approaches its end, or if in order to reach this end it must often go back and set out on a new path; or likewise if it proves impossible for the different co-workers to achieve unanimity as to the way in which they should pursue their common aim; then we may be sure that such a study is merely groping about, that it is still far from having entered upon the secure course of a science; and it is already a service to reason if we can possibly find that path for it, even if we have to give up as futile much of what was included in the end previously formed without deliberation. That from the earliest times logic has traveled this secure course can What is further remarkable about logic is that until now it has also been unable to take a single step forward, and therefore seems to all appearance to be finished and complete. For if some moderns have thought to enlarge [the science of logic] by interpolating psychological chapters about our different cognitive powers (about imagination, wit), or metaphysical chapters about the origin of cognition or the different kinds of certainty in accordance with the diversity of objects (about idealism, skepticism, etc.), or anthropological chapters about our prejudice (about their causes and remedies), then this proceeds only from their ignorance of the peculiar nature of this science. It is not an improvement but a deformation of the sciences when their boundaries are allowed to run over into one another; the boundaries of logic, however, are determined quite precisely by the fact that logic is the science that exhaustively presents and strictly proves nothing but the formal rules of all thinking (whether this thinking be empirical or a priori, whatever origin or object it may have, and whatever contingent or natural obstacles it may meet with in our minds). MMT: "If some modern philosophers thought to enlarge it, by introducing VG: "formal rules of thinking": Kant is saying that logic is not really a science, just a collection of empty rules of thinking. See his next statments for logic as mere introduction to the sciences. For the advantage that has made it so successful logic has solely its RPW: “Kant says, ‘reason has insight only into that which it produces after a plan of its own.’ That’s a very, very profound and deep idea that Kant just throws into the preface and will become clear only later on in these lectures. Essentially, what Kant is telling us is that what we can understand, either in the world of physical science or in the world of moral principles, is only that which we ourselves put into it. We encounter ourselves when we do physics, we encounter ourselves, our own reason, when we do ethics. That’s a very deep idea, and we’ll come back to it.” VG: Logic [is self-contained, does not deal directly with objects in the world] has to do with itself and its own form, and this is why logic can be certain and true. These are the general rules of thought, and we take them from ourselves, our own minds. NSC: "That logic should have attained the secure method of science is due to its limitation to the mere a priori form of knowledge. For metaphysics this is far more difficult, since it 'has to deal not with itself alone, but also with objects' ... The second edition preface, in thus emphasising the objective aspect of the problem, is led to characterise in a more complete manner the method to be followed in the Critical enquiry. How can the Critique, if it is concerned, as both editions agree in insisting, only with the a priori which originates in human reason, solve the specifically metaphysical problem, viz. that of determining the independently real? How can an idea in us refer to, and constitute knowledge of, an object? The larger part of the preface to the second edition is devoted to the Critical solution of this problem." VG: knowledge of an object, objective knowledge: What is objective knowledge, or knowledge of an object? A popular answer was, we have objective knowledge when, in a sense, we have a copy of that object in the mind; when the mind is the mirror of nature. But how can we know that the mind is actually a good mirror? Kant is going to say that to know does not mirror. When the senses give us images, these do not become "knowledge" unless they are fitted into a larger whole; for example, we may think we see something, like a cow in the room, but we need to compare that perception with everything we know about the world, and we'll likely find that we were mistaken. This is an easy example, but [bearing in mind that in the odd case, there could be a cow in the room, and sometimes we chance upon brand new but anomalous information] we engage in this process of judgment all the time with higher level purported aspects of knowledge. How much more difficult, naturally, must it be for reason to enter upon the secure path of a science if it does not have to do merely with itself, but has to deal with objects too; hence logic as a propadeutic ["preliminary instruction"] constitutes only the outer courtyard, as it were, to the sciences; and when it comes to information, a logic may indeed be presupposed in judging about the latter, but its acquisition must be sought in the sciences properly and objectively so called. MJT: "Hence, logic is properly only a propaedeutic -- forms, as it were, the vestibule [a precursor] of the sciences; and while it is necessary to enable us to form a correct judgement with regard to the various branches of knowledge, still the acquisition of real, substantive knowledge is to be sought only in the sciences properly so called, that is, in the objective sciences." Insofar as there is to be reason in these sciences, something in them MJT: "Now these sciences, if they can be termed rational at all, must Mathematics and physics are the two theoretical cognitions of reason Mathematics has, from the earliest times to which the history of VG: We had to re-understand mathematics as something that we ourselves generate before it could take the path of a secure science. The history of this revolution in the way of thinking - which was far more important than the discovery of the way around the famous Cape [of Good Hope] - and of the lucky one who brought it about, has not been preserved for us. But the legend handed down to us by Diogenes Laertius - who names the reputed inventor of the smallest elements of geometrical demonstrations, even of those that, according to common judgment, stand in no need of proof - proves that the memory of the alteration wrought by the discovery of this new path in its earliest footsteps must have seemed exceedingly important to mathematicians, and was thereby rendered unforgettable. A new light broke upon the first person who demonstrated the isosceles triangle (whether he was called "Thales" or had some other name). For he found that what he had to do was not to trace what he saw in this figure, or even trace its mere concept, and read off, as it were, from the properties of the figure; but rather that he had to produce the latter from what he himself thought into the object and presented (through construction) according to a priori concepts, and that in order to know something securely a priori he had to ascribe to the thing nothing except what followed necessarily from what he himself had put into it in accordance with its concept. NSC: "This method consists, not in being led by nature as in leading-strings, but in interrogating nature in accordance with what reason produces on its own plan. The method of the geometrician does not consist in the study of figures presented to the senses... By that means no new knowledge could ever be attained." MMT: "A new light flashed on the first man who demonstrated the properties of the isosceles triangle... for he found [important] not ... what he saw in the figure, or the mere concept of that figure, and Editor’s note: I believe Kant is saying something similar to what many have heard from an instructor in geometry: the triangle that we draw on the board is but imperfect representation of the true triangle. On the board, or on paper, lines are always imperfect, we cannot produce an absolutely perfect isosceles triangle with human artifice. The true equilateral triangle is an abstract ideal, call it Platonic, or something that we create mentally. We have never seen the true triangle drawn on a board. All this considered, the triangle, in a meaningful way, consists of what we put into the concept, not from what we derive from the image on the board. It took natural science much longer to find the highway of science; When Galileo rolled balls of a weight chosen by himself down an * Here I am not following exactly the thread of the history of the experimental method, whose first beginnings are also not precisely known. a light dawned on all those who study nature. They comprehended that reason has insight only into what it itself produces according to its own design; that it must take the lead with principles for its judgments according to constant laws and compel nature to answer its questions, rather than letting nature guide its movements by keeping reason, as it were, in leading-strings; for otherwise accidental observations, made according to no previously designed plan, can never connect up into a necessary law, which is yet what reason seeks and requires.

NSC: Galileo "determined the principles according to which alone concordant phenomena can be admitted as laws of nature, and then by experiment compelled nature to answer the questions which these principles suggest." Reason, in order to be taught by nature, must approach nature with its principles in one hand, according to which alone the agreement among appearances can count as laws, and, in the other hand, the experiments thought out in accordance with these principles - yet in order to be instructed by nature not like a pupil, who has recited to him whatever the teacher wants to say, but like an appointed judge who compels witnesses to answer the questions he puts to them. Thus even physics owes the advantageous revolution in its way of thinking to the inspiration that what reason would not be able to know of itself and has to learn from nature, it has to seek in the latter (though not merely ascribe to it) in accordance with what reason itself puts into nature. This is how natural science was first brought to the secure course of a science after groping about for so many centuries. VG: While math deals with concepts that we create, such as the triangle, physics has to do with objects in the world. Nevertheless, says Kant, there is something that we put into the empirical sciences. Modern science is more than just going out in nature and observing, but, with the experimental method, we take the reins and, according to reason’s principles, we construct experiments reflecting these principles. Editor’s note: What does it mean for reason to put something into nature? Isn’t nature what it is, inviolably so? Nature is what it is (although quantum mechanics would later posit that we alter nature by observing it), but our interpretations of nature are fluid, and it is these interpretations which come to us as representing what we deem to be the reality of nature. It is like this: When a scientist questions nature with experiments, the posed questions reflect an underlying hypothesis; in other words, the scientist already has an idea of what the answer might be, and received data which does not relate to the hypothesis can easily be ignored: “reason has insight only into what it itself produces according to its own design.” (See the lectures of Prof. Goldman concerning flawed reasoning by scientists, “assuming the conclusion.”) Therefore, in this sense, from the advent of what is called modern science with the experimental method, we put something into nature. Metaphysics - a wholly isolated speculative cognition of reason that MJT: “reason thus is supposed to be its own pupil”: [In metaphysics it is supposed that] “reason is the pupil of itself alone.” For in it reason continuously gets stuck, even when it claims a priori insight (as it pretends) into those laws confirmed by the commonest experience. In metaphysics we have to retrace our path countless times, because we find that it does not lead where we want to go, and it is so far from reaching unanimity in the assertions of its adherents that it is rather a battlefield, and indeed one that appears to be especially determined for testing one's powers in mock combat; on this battlefield no combatant has ever gained the least bit of ground, nor has any been able to base any lasting possession on his victory. MJT: “this science [metaphysics] appears to furnish an arena specially adapted for the display of skill or the exercise of strength in mock-contests—a field in which no combatant ever yet succeeded in gaining an inch of ground, in which, at least, no victory was ever yet crowned with permanent possession.” Hence there is no doubt that up to now the procedure of metaphysics has been a mere groping, and what is the worst, a groping among mere concepts. Now why is it that here the secure path of science still could not be Editor’s note: Kant wonders if answers are available at all from metaphysics. But success here must be possible, he thinks, else why should nature have burdened us with such restless questions? VG: This devotion to seeking for truth, suggests to Kant, that there ought to exist a way of satisfaction here; this is a teleological, goal-oriented view. I should think that the examples of mathematics and natural science, Editor’s note: What was the “essential element” that provided for success in the other sciences? Let us attempt to “imitate”, says Kant, this vital item in application to metaphysics. Up to now it has been assumed that all our cognition must conform to VG: In three different ways, for logic, math, and physics, we see Kant suggesting that we put something into an object of knowledge. In these three, we are being active, we are using our understanding, our constructions, our experiments, and this, he intimates, is what is necessary to have knowledge. In metaphysics we do not have this approach which has done well elsewhere, we just have people disagreeing with each other, but let us see if putting something into metaphysics will move us forward. Editor’s note: “a priori cognition of them, which is to establish something about objects before they are given to us": Kant is leaning in the direction of obtaining some information about objects in the world before observation and science, and this would become a form of our putting something into an object of knowledge. VG: When the Sun was seen to be central, the Church immediately recognized this as a displacement of Man (and the Church) from prime importance. Kant, however, by positing that we put something into scientific searchings, places Man at the center of creative investigations. This would be just like the first thoughts of Copernicus, who, when he did not make good progress in the explanation of the celestial motions if he assumed that the entire celestial host revolves around the observer, tried to see if he might not have greater success if he made the observer revolve and left the stars at rest. Now in metaphysics we can try in a similar way regarding the intuition of objects. Editor's note: There is a phrase, the “Copernican turn,” referring to “an inversion of the way we view nature” (Stanford.edu); “indicating a critical turning point that presents an unstable situation and creates uncertainty. As a consequence it is also a decisive turning point at which something new is being held at bay. Something that one needs to face, and address, and keep apace with” (Sverre Raffnsøe). VG: Our efforts to allow objects in the world to shape our cognitions have not produced much, so maybe we should see if the objects might be shaped by our cognitions. This reversal, in principle, is what Copernicus tried with seeing the Sun at the center and not the Earth. “intuition of objects”: These are objects of the world that have been altered by human cognition and sensory experience; as per the reversal inspired by Copernicus. If intuition has to conform to the constitution of the objects, then I do not see how we can know anything of them a priori; but if the object (as an object of the senses) conforms to the constitution of our faculty of intuition, then I can very well represent this possibility to myself. MMT: "We have here the same case as with the first thought of VG: Kant, in the spirit of Copernicus, is suggesting a reversal. If we think that our cognitions, our attempts to get knowledge, have to conform, fit or shape themselves, to objects in the world – which is the general view -- we discover that this method has been a disaster. Well, let’s try the opposite. We have seen in all these other sciences that we put something into the world, so, concerning a better approach to metaphysics, we should entertain the idea that objects might conform to our cognitions; that, we, in a sense, impress something onto the object. Intuitions have to do with how information comes to us, by sensations. VG: Gardner says that this is Kant’s fundamental “problem of reality” with his solution as the Copernican Revolution. Here is the problem: How can we know that our thoughts, our representations of reality, are actually accurate images of reality? How do we know that we are in fact in touch with reality? that, the kind of things we think about are actually the things that exist in reality? To take ourselves seriously here is to presuppose that our cognitive abilities are equal to the task of apprehending the real world. Philosophers prior to Kant dealt with this question by presupposing that reality is something independent of us: Gardner on page 35: The problem is rooted in what we are naturally disposed to think. On the story told by pre-philosophical common sense … there is first of all a set of objects composing a world, into which the subject is then introduced as a further item; when the subject’s eyes are opened and its cognitive functions are in working order, the world floods in and knowledge of the world results. How do we know that this “flooding in” leaves us with accurate representations of reality? How do we know that we’re the right kind of thing for reality to flow into? All the pre-Kantian ideas, called “transcendental realism”, as opposed to Kant’s “transcendental idealism,” all these, says Gardner: reduce on examination to the bare, non-explanatory claim that we represent real things because they affect us and because we have an immanent capacity to represent them. Editor's note: "non-explanatory claim": in other words, it's just an assumption, with no attempt to offer meaning. VG: Things out there, they said, are what they are, independent of our cognitive powers. The rationalists posited there is something in reason to bridge the gap which, they said, is God. And the assumption was, if we have the ability to know God, then we can know the world, as well. The empiricists said that we know by our senses, but we don’t know about the objects that generate the impressions So the idea is, these things out there affect us, and we just are the right kind of entity to process all this “flooding in.” But there’s no further explanation here from the earlier sources. They don’t even try to explain. But Kant does want to answer, and his answer is his own version of the Copernican Revolution. And what is this new way? Gardner, pg 38: Pre-Copernican philosophical systems, according to Kant, set out by assuming a domain of objects which are conceived as having being, and a constitution of their own – a class of real things. In this sense, previous philosophical systems are one and all realist. Yet because I cannot stop with these intuitions, if they are to become cognitions, but must refer them as representations to something as their object and determine this object through them, I can assume either that the concepts through which I bring about this determination also conform to the objects, and then I am once again in the same difficulty about how I could know anything about them a priori, or else I assume that the objects, or what is the same thing, the experience in which alone they can be cognized (as given objects) conforms to those concepts, in which case I immediately see an easier way out of the difficulty, since experience itself is a kind of cognition requiring the understanding, whose rule I have to presuppose in myself before any object is given to me, hence a priori, which rule is expressed in concepts a priori, to which all objects of experience must therefore necessarily conform, and with which they must agree. “because I cannot stop with these intuitions”: Kant cannot stop the discussion here with intuitions because they’re linked to concepts. And are these concepts also subject to the same reversal of orientation? Do our cognitions shape these, as well? As for objects insofar as they are thought merely through reason, and necessarily at that, but that (at least as reason thinks them) cannot be given in experience at all - the attempt to think them (for they must be capable of being thought) will provide a splendid touchstone of what we assume as the altered method of our way of thinking, namely that we can cognize of things a priori only what we ourselves have put into them.* * This method, imitated from the method of those who study nature, thus consists in this: to seek the elements of pure reason in that which admits of being confirmed or refuted through an experiment. Now the propositions of pure reason, especially when they venture beyond all boundaries of possible experience, admit of no test by experiment with their objects (as in natural science): thus to experiment will be feasible only with concepts and principles that we assume a priori by arranging the latter so that the same objects can be considered from two different sides, on the one side as objects of the senses and the understanding for experience, and on the other side as objects that are merely thought at most for isolated reason striving beyond the bounds of experience. If we now find that there is agreement with the principle of pure reason when things are considered from this twofold standpoint, but that an unavoidable conflict of reason with itself arises with a single standpoint, then the experiment decides for the correctness of that distinction. This experiment succeeds as well as we could wish, and it promises to But from this deduction of our faculty of cognizing a priori in the first part of metaphysics, there emerges a very strange result, and one that appears very disadvantageous to the whole purpose with which the second part of metaphysics concerns itself, namely that with this faculty we can never get beyond the boundaries of possible experience, which is nevertheless precisely the most essential occupation of this science. NSC: “The two ‘parts’ of metaphysics. Kant is here drawing the important distinction, which is one result of his new standpoint, between immanent and transcendent metaphysics.” But herein lies just the experiment providing a checkup on the truth of the result of that first assessment of our rational cognition a priori, namely that such cognition reaches appearances only, leaving the thing in itself as something actual for itself but uncognized by us. VG: Kant here introduces his famous distinction between appearances and “the thing in itself"; discussed at length later in the Critique. NSC: “Reason must be regarded as self-legislative in all the domains of our possible knowledge. Objects must be viewed as conforming to human thought, not human thought to the independently real… The method of procedure which it prescribes is, he declares, analogous to that which was followed by Copernicus, and will be found to be as revolutionary in its consequences. From this new standpoint Kant develops phenomenalism on rationalist lines. He professes to prove that though our knowledge is only of appearances, it is conditioned by a priori principles. His “Copernican hypothesis,” so far from destroying positive science, is, he claims, merely a philosophical extension of the method which it has long been practising. Since all science worthy of the name involves a priori elements, it can be accounted for only in terms of the new hypothesis. Only if objects are regarded as conforming to our forms of intuition, and to our modes of conception, can they be anticipated by a priori reasoning. Science can be a priori just because, properly understood, it is not a rival of metaphysics, and does not attempt to define the absolutely real.” “our rational cognition a priori … reaches appearances only”: reason deals with appearances only and not the thing in itself. Editor’s note: the famous dichotomy of appearance and thing in itself was introduced as part of Kant’s Copernican Revolution. There is the surface appearance that the Sun moves around the Earth, but the deeper thing in itself is much different. For that which necessarily drives us to go beyond the boundaries of experience and all appearances is the unconditioned, which reason necessarily and with every right demands in things in themselves for * This experiment of pure reason has much in common with what the chemists sometimes call the experiment of reduction, or more generally the synthetic procedure. The analysis of the metaphysician separated pure a priori knowledge into two very heterogeneous elements, namely those of the things as appearances and the things in themselves. The dialectic once again combines them, in unison with the necessary rational idea of the unconditioned, and finds that the unison will never come about except through that distinction, which is therefore the true one. Editor’s note: With cursory reading, the meaning of Copernican Revolution would seem to be straightforward. But there is great debate here among Kant scholars, even with assertions that it is a misleading analogy. See the following discussion by Norman Kemp. Much of it comes down to this: Copernicus removed Man from the center of the universe, but Kant affirms the central role of Man and human cognition in determining reality. NSC: “The Copernican hypothesis: Kant’s comparison of his new hypothesis to that of Copernicus has generally been misunderstood. The reader very naturally conceives the Copernican revolution in terms of its main ultimate consequence, the reduction of the earth from its proud position of central pre-eminence. But that does not bear the least analogy to the intended consequences of the Critical philosophy. The direct opposite is indeed true. Kant’s hypothesis is inspired by the avowed purpose of neutralising the naturalistic implications of the Copernican astronomy. His aim is nothing less than the firm establishment of what may perhaps be described as a Ptolemaic, anthropocentric metaphysics. Even some of Kant’s best commentators have interpreted the analogy in the above manner… Alexander… also endorses this interpretation in the following terms: “It is very ironical that Kant himself signalised the revolution which he believed himself to be effecting as a Copernican revolution. But there is nothing Copernican in it except that he believed it to be a revolution… For his revolution, so far as it was one, was accurately anti-Copernican.” … Copernicus by his proof of the “hypothesis” (his own term) of the earth’s motion sought only to achieve a more harmonious ordering of the Ptolemaic universe. And as thus merely a simplification of the traditional cosmology, his treatise could fittingly be dedicated to the reigning Pope. The sun upon which our terrestrial life depends was still regarded as uniquely distinct from the fixed stars; and our earth was still located in the central region of a universe that was conceived in the traditional manner as being single and spherical. Giordano Bruno was the first, a generation later, to realise the revolutionary consequences to which the new teaching, consistently developed, must inevitably lead. It was he who first taught what we have now come to regard as an integral part of Copernicus’ revolution, the doctrine of innumerable planetary systems side by side with one another in infinite space. Copernicus’ argument starts from the Aristotelian principle of relative motion. To quote Copernicus’ exact words: “All apprehended change of place is due to movement either of the observed object or of the observer, or to differences in movements that are occurring simultaneously in both. For if the observed object and the observer are moving in the same direction with equal velocity, no motion can be detected. Now it is from the earth that we visually apprehend the revolution of the heavens. If, then, any movement is ascribed to the earth, that motion will generate the appearance of itself in all things which are external to it, though as occurring in the opposite direction, as if everything were passing across the earth. This will be especially true of the daily revolution. For it seems to seize upon the whole world, and indeed upon everything that is around the earth, though not upon the earth itself.... As the heavens, which contain and cover everything, are the common locus of things, it is not at all evident why it should be to the containing rather than to the contained, to the located rather than to the locating, that a motion is to be ascribed.” The apparently objective movements of the fixed stars and of the sun are mere appearances, due to the projection of our own motion into the heavens. “The first and highest of all the spheres is that of the fixed stars, self-containing and all-containing, and consequently immobile, in short the locus of the universe, by relation to which the motion and position of all the other heavenly bodies have to be reckoned.” Now after speculative reason has been denied all advance in this field of the supersensible, what still remains for us is to try whether there are not data in reason's practical data for determining that transcendent rational concept of the unconditioned, in such a way as to reach beyond the boundaries of all possible experience, in accordance with the wishes of metaphysics, cognitions a priori that are possible, but only from a practical standpoint. By such procedures speculative reason has at least made room for such an extension, even if it had to leave it empty; and we remain at liberty, indeed we are called upon by reason to fill it if we can through practical data of reason. * * In the same way, the central laws of the motion of the heavenly bodies established with certainty what Copernicus assumed at the beginning only as a hypothesis, and at the same time they proved the invisible force (of Newtonian attraction) that binds the universe which would have remained forever undiscovered if Copernicus had not ventured, in a manner contradictory to the senses yet true, to seek for the observed movements not in the objects of the heavens but in their observer. In this Preface I propose the transformation in our way of thinking presented in criticismh merely as a hypothesis, analogous to that other hypothesis, only in order to draw our notice to the first attempts at such a transformation, which are always hypothetical, even though in the treatise itself it will be proved not hypothetically but rather apodictically from the constitution of our representations of space and time and from the elementary concepts of the understanding. VG: Kant writes a new preface for the second edition. He attempts to coax us to enter his view by speaking of other fields of study. He talks about logic, math, and science and discusses what needed to happen in order for them to be successful. And then he tells us that, for his metaphysics, there is a commonality with these other studies. At first he implies that he will introduce hypotheses for his metaphysics, along the lines of open investigation with the other sciences, but then takes it all away in the above footnote. What he has to say will be “proved not hypothetically but apodictically”; in other words, “yes, I spoke of hypotheses to invite your interest, but actually I’m not in doubt and will offer you clear convincing evidence that what I say here is the way it is.” Now the concern of this critique of pure speculative reason consists For pure speculative reason has this peculiarity about it, that it can and should measure its own capacity according to the different ways for choosing the objects of its thinking, and also completely enumerate the manifold ways of putting problems before itself, so as to catalog the entire preliminary sketch of a whole system of metaphysics; because, regarding the first point, in a priori cognition nothing can be ascribed to the objects except what the thinking subject takes out of itself, and regarding the second, pure speculative reason is, in respect of principles of cognition, a unity entirely separate and subsisting for itself, in which, as in an organized body, every part exists for the sake of all the others as all the others exist for its sake, and no principle can be taken with certainty in one relation unless it has at the same time been investigated in its thoroughgoing relation to the entire use of pure reason. But then metaphysics also has the rare good fortune, enjoyed by no other rational science that has to do with objects (for logic deals only with the form of thinking in general), which is that if by this critique it has been brought onto the secure course of a science, then it can fully embrace the entire field of cognitions belonging to it and thus can complete its work and lay it down for posterity as a principal framework that can never be enlarged, since it has to do solely with principles and the limitations on their use, which are determined by the principles themselves. Hence as a fundamental science, metaphysics is also bound to achieve this completeness, and we must be able to say of it: nil actum reputans, si quid superesset agendum. "Thinking nothing done if something more is to be done." The correct quotation is: "Caesar in omnia praeceps, nil actum credens, cum quid superesset agendum, instat atrox" (Caesar, headlong in everything, believing nothing done while something more remained to be done, pressed forward fiercely) (Lucan, De bello civili 2:657). But it will be asked: What sort of treasure is it that we intend to leave On a cursory overview of this work, one might believe that one perceives it to be only of negative utility, teaching us never to venture with speculative reason beyond the boundaries of experience; and in fact that is its first usefulness. But this utility soon becomes positive when we become aware that the principles with which speculative reason ventures beyond its boundaries do not in fact result in extending our use of reason, but rather, if one considers them more closely, inevitably result in narrowing it by threatening to extend the boundaries of sensibility, to which these principles really belong, beyond everything, and so even to dislodge the use of pure (practical) reason. Hence a critique that limits the speculative use of reason is, to be sure, to that extent negative, but because it simultaneously removes an obstacle that limits or even threatens to wipe out the practical use of reason, this critique is also in fact of positive and very important utility, as soon as we have convinced ourselves that there is an absolutely necessary practical use of pure reason (the moral use), in which reason unavoidably extends itself beyond the boundaries of sensibility, without needing any assistance from speculative reason, but in which it must also be made secure against any counteraction from the latter, in order not to fall into contradiction with itself. To deny that this service of criticisma is of any positive utility In the analytical part of the critique it is proved that space and time are only forms of sensible intuition, and therefore only conditions of the existence of the things as appearances, further that we have no concepts of the understanding and hence no elements for the cognition of things except insofar as an intuition can be given corresponding to these concepts, consequently that we can have cognition of no object as a thing in itself, but only insofar as it is an object of sensible intuition, i.e. as an appearance; from which follows the limitation of all even possible speculative cognition of reason to mere objects of experience. Yet the reservation must also be well noted, that even if we cannot cognize these same objects as things in themselves, we at least must be able to think them as things in themselves.* * To cognize an object, it is required that I be able to prove its possibility (whether by the testimony of experience from its actuality or a priori through reason). But I can think whatever I like, as long as I do not contradict myself, i.e., as long as my concept is a possible thought, even if I cannot give any assurance whether or not there is a corresponding object somewhere within the sum total of all possibilities. But in order to ascribe objective validity to such a For otherwise there would follow the absurd proposition that there is an appearance without anything that appears. Now if we were to assume that the distinction between things as objects of experience and the very same things as things in themselves, which our critique has made necessary, were not made at all, then the principle of causality, and hence the mechanism of nature in determining causality, would be valid of all things in general as efficient causes. I would not be able to say of one and the same thing, e.g., the human soul, that its will is free and yet that it is simultaneously subject to natural necessity, i.e., that it is not free, without falling into an obvious contradiction; because in both propositions I would have taken the soul in just the same meaning, namely as a thing in general (as a thing in itself), and without prior critique, I could not have taken it otherwise. But if the Critique has not erred in teaching that the object should be taken in a twofold meaning, namely as appearance or as thing in itself; if its deduction of the pure concepts of the understanding is correct, and hence the principle of causality applies only to things taken in the first sense, namely insofar as they are objects of experience, while things in the second meaning are not subject to it; then just the same will is thought of in the appearance (in visible actions) as necessarily subject to the law of nature and to this extent not free, while yet on the other hand it is thought of as belonging to a thing in itself as not subject to that law, and hence free, without any contradiction hereby occurring. Now although I can not cognize my soul, considered from the latter side, through any speculative reason (still less through empirical observation), and hence I cannot cognize freedom as a property of any being to which I ascribe effects in the world of sense, because then I would have to cognize such an existence as determined, and yet not as determined in time (which is impossible, since I cannot support my concept with any intuition), nevertheless, I can think freedom to myself, i.e., the representation of it at least contains no contradiction in itself, so long as our critical distinction prevails between the two ways of representing (sensible and intellectual), along with the limitation of the pure concepts of the understanding arising from it, and hence that of the principles flowing from them. cognize vs think: Kant says that he cannot know (with certainty) that he is free, but he can think of himself as free. And this freedom, according to his view, is enough to create morality. Now suppose that morality necessarily presupposes freedom (in But then, since for morality I need nothing more than that freedom should not contradict itself, that it should at least be thinkable that it should place no hindrance in the way of the mechanism of nature in the same action (taken in another relation), without it being necessary for me to have any further insight into it: the doctrine of morality asserts its and the doctrine of nature its own, which, however, would not have occurred if criticism had not first taught us of our unavoidable ignorance Thus I cannot even assume God, freedom and immortality for the sake of the necessary practical use of my reason unless I simultaneously deprive speculative reason of its pretension to extravagant insights; because in order to attain to such insights, speculative reason would have to help itself to principles that in fact reach only to objects of possible experience, and which, if they were to be applied to what cannot be an object of experience, then they would always actually transform it into an appearance, and thus declare all practical extension of pure reason to be impossible. Thus I had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith; and the dogmatism of metaphysics, i.e., the prejudice that without criticism reason can make progress in metaphysics, is the true source of all unbelief conflicting with morality, which unbelief is always very dogmatic. RPW: “a faith in the existence of God which is not supported by any rational theology, by any rational metaphysics.” VG: knowledge vs faith: “the most famous statement in the B preface.” Kant has asserted that he cannot cognize or know with certainty that he is free or that there is a God, but he makes room for the possibility of the higher order. Thus even if it cannot be all that difficult to leave to posterity For there has always been some metaphysics or other to be met with in the world, and there will always continue to be one, and with it a dialectic of pure reason, because dialectic is natural to reason. Hence it is the first and most important occupation of philosophy to deprive dialectic once and for all of all disadvantageous influence, by blocking off the source of the errors. With this important alteration in the field of the sciences, and with If that has never happened, and if it can never be expected to happen, owing to the unsuitability of the common human understanding for such subtle speculation; if rather the conviction that reaches the public, insofar as it rests on rational grounds, had to be effected by something The alteration thus concerns only the arrogant claims of the schools, which would gladly let themselves be taken for the sole experts and guardians of such truths (as they can rightly be taken in many "What he knows no more than I, he alone wants to seem to know." The correct quotation is "Quod mecum ignorat, solus volt scire videri" (What is unknown to me, that alone he wants to seem to know) (Horace, Epistles 2 .1 .87) Yet care is taken for a more equitable claim on the part of the speculative philosopher. He remains the exclusive trustee of Through criticism alone can we sever the very root of materialism, fatalism, atheism, of freethinking unbelief, of enthusiasm and superstition, which can become generally injurious, and finally also of idealism and skepticism, which are more dangerous to the schools and can hardly be transmitted to the public. If governments find it good to concern themselves with the affairs of scholars, then it would accord better with their wise solicitude both for the sciences and for humanity if they favored the freedom of such a critique, by which alone the treatments of reason can be put on a firm footing, instead of supporting the ridiculous despotism of the schools, which raise a loud cry of public danger whenever someone tears apart their cobwebs, of which the public has never taken any notice, and hence the loss of which it can also never feel. Criticism is not opposed to the dogmatic procedure of reason in its Dogmatism is therefore the dogmatic procedure of pure reason, LT: Dogmatism: “The word ‘dogmatism’ comes from the Greek ‘dogma’ which means belief or opinion, and in traditional Christian theology the dogmata are the articles of faith that are considered to be those beliefs that are essential to hold if one is to be a Christian. Used in this sense, the word ‘dogmatic’ did not originally have a negative connotation. Kant, however, uses the word ‘dogmatic’ in a negative sense to imply a belief that is held with insufficient justification, and he regarded rationalist metaphysics, which claimed to provide us with theoretical insight into how things are in themselves, as dogmatic in this negative sense. Kant positioned his own critical philosophy as occupying a middle ground between dogmatism and skepticism.” ... carried out systematically in accordance with the strictest re- Those who reject his kind of teaching and simultaneously the procedure of the critique of pure reason can have nothing else in mind except to throw off the fetters of science altogether, and to transform work Concerning this second edition, I have wanted, as is only proper, I hope this system will henceforth maintain itself in this unalterability. It is not self-conceit that justifies my trust in this, but rather merely the evidence drawn from the experiment showing that the result My revisions of the mode of presentation* * The only thing I can really call a supplement, and that only in the way of proof, is what I have said at [B] 273 in the form of a new refutation of psychological idealism, and a strict proof (the only possible one, I believe) of the objective reality of outer intuition. No matter how innocent idealism may be held to be as regards the essential ends of metaphysics (though in fact it is not so inno- If I could combine a determination of my existence through intellectual intuition simultaneously with the intellectual consciousness of my existence, in the representation I am, which accompanies all my judgments and actions of my understanding, then no consciousness of a relation to something outside me would necessarily belong to this. But now that intellectual consciousness does to be sure precede, but the inner intuition, in which alone my existence can be determined, is sensible, and is bound to a condition of time; however, this determination, and hence inner experience itself, depends on something permanent, which is not in me, and consequently must be outside me, and I must consider myself in relation to it; thus for an experience in general to be possible, the reality of outer sense is necessarily bound up with extend only to this point (namely, only to the end of the first chapter of the Transcendental Dialectic) and no further, because time was too short, and also in respect of the rest of the book no misunderstanding on the part of expert and impartial examiners has come my way, whom I have not been able to name with the praise due to them; but the attention I have paid to their reminders will be evident to them in the appropriate passages. This improvement, however, is bound up with a small loss for the reader, which could not be guarded against without making the book too voluminous: namely, various things that are not essentially required for the completeness of the whole had to be omitted or treated in an abbreviated fashion, despite the fact that some readers may not like doing without them, since they could still be useful in another respect; only in this way could I make room for what I hope is a more comprehensible presentation, which fundamentally alters absolutely nothing in regard to the propositions or even their grounds of proof, but which departs so far from the previous edition in the method of presentation that it could not be managed through interpolations. This small loss, which in any case can be compensated for, if anyone likes, by comparing the first and second editions, is, as I hope, more than compensated for by greater comprehensibility. In various public writings (partly in the reviews of some books, partly in special treatises) I have perceived with gratitude and enjoyment that the spirit of well-groundedness has not died out in Germany, but has only been drowned out for a short time by the fashionable noise of a freedom of thought that fancies itself ingenious, and I see that the thorny paths of criticism, leading to a science of pure reason that is scholastically rigorous but as such the only lasting and hence the most necessary science, has not hindered courageous and clear minds from mastering them. To these deserving men, who combine well-groundedness of insight so fortunately with the talent for a lucid presentation (something I am conscious of not having myself), I leave it to complete my treatment, which is perhaps defective here and there in this latter regard. For in this case the danger is not that I will be refuted, but that I will not be understood. For my own part, from now on I cannot let myself become involved in controversies, although I shall attend carefully to all hints, whether they come from friends or from opponents, so that I may utilize them, in accordance with this propaedeutic, in the future execution of the system. Since during these labors I have come to be rather advanced in age (this month I will attain my sixty-fourth year), I must proceed frugally with my time if I am to carry out my plan of providing the metaphysics both of nature and of morals, as confirmation of the correctness of the critique both of theoretical and practical reason; and I must await the illumination of those obscurities that are hardly to be avoided at the beginning of this work, as well as the defense of the whole, from those deserving men who have made it their own. Any philosophical treatise may find itself under pressure in particular passages (for it cannot be as fully armored as a mathematical treatise), while the whole structure of the system, considered as a unity, proceeds without the least danger; when a system is new, few have the adroitness of mind to gain an overview of it, and because all innovation is an inconvenience to them, still fewer have the desire to do so. Also, in any piece of writing apparent contradictions can be ferreted out if individual passages are torn out of their context and compared with each other, especially in a piece of informal discourse that in the eyes of those who rely on the judgment of others cast a disadvantageous light On that piece of writing but that can be very easily resolved by someone who has mastered the idea of the whole. Meanwhile, if a theory is really durable, then in time the effect of action and reaction, which at first seemed to threaten it with great danger, will serve only to polish away its rough spots, and if men of impartiality, insight, and true popularity make it their business to do this, then in a short time they will produce even the required elegance. Konigsberg, in the month of April, I787

the page is under construction

|

||

|

|