|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Kant The Critique of Pure Reason Preface, First Edition (A) 1781

return to 'critique of pure reason' contents page

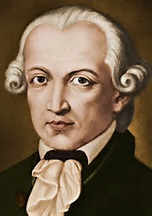

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

auxiliary sources for 'The Critique' VG: Professor Victor Gijsbers, Netherlands, youtube lectures DR: Professor Daniel Robinson, Oxford, youtube lectures RPW: Prof. Robert Paul Wolff, youtube lectures PG: translation, Paul Guyer MM: translation, Max Muller: "[His] main merit, as he has very justly claimed, is his greater accuracy in rendering passages in which a specially exact appreciation of the niceties of German idiom happens to be important for the sense." TN TN: translation, N.K. Smith PR: translation-commentary, P.M. Rudisill NKC: commentary, N.K. Smith SG: commentary, Sebastian Gardner SP: glossary, Stephen Palmquist LT: glossary, Lucas Thorpe

*********************************************

The Critique of Pure Reason

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION 1781 DR: Kant uses “pure” to mean, without reference to experience, therefore the title indicates an analysis of reason untainted by the influence of sensory experience. Kant himself affirms this general definition within the preface. Human reason, in one sphere of its cognition, is called upon to consider questions, which it cannot decline, as they [the questions] are presented by its own nature, but which it cannot answer, as they [the questions] transcend every faculty of the mind. NKC: “Human reason is ineradicably metaphysical. It is haunted by questions which, though springing from its very nature, none the less transcend its powers.” TN: "Human reason has this peculiar fate that, in one species of its knowledge, it is burdened by questions which, as prescribed by the very nature of reason itself, it is not able to ignore, but which, as transcending all its powers, it is also not able to answer." VG: Reason itself posits certain questions that reason cannot answer. Kant will go on to explain that the larger questions, what is the soul, God, etc., become the domain of some philosophers, but they lack the ability, via reason alone, to answer these questions. It [human reason] falls into this difficulty without any fault of its own. VG: It is reason itself that asks these larger questions, not some outside source. And so we need to ask not just why reason asks these questions but why it cannot provide answer. It [human reason] begins with principles, which cannot be dispensed with in the field of experience, and the truth and sufficiency of which [referring to the ‘principles’] are, at the same time, insured by experience. PR: "It begins with fundamental propositions, whose use in the course of experience is unavoidable and, at the same time, confirmed by that experience itself." MM: "It begins with principles which, in the course of experience, it must follow, and which are sufficiently confirmed by experience." is Kant saying: when we use reason, we do so in the field of experience, ie sensory perception, and these principles, which we can’t get away from when we use reason, are proven and grounded, are found to be true and sufficient, in the arena of experience, that is, are “insured” and established by the field of experience Kant is talking about inherent problems befalling human reason. This human reason begins with certain principles, which are found to be true and substantive, “insured” to be such as they enter the arena of experience; meaning, we learn by experience that these principles are true. But even though the principles are found to be solid, in themselves, still they are not enough to answer the more profound questions raised by Reason’s own nature, about itself, as these lofty questions are too high, transcend, every faculty and capacity of the human mind is Kant saying, that when we use reason, we do so with sensory experience and principles, with the principles reinforced by experience, and therefore, these cannot be used as a foundation of reason With these principles it [human reason] rises, in obedience to the laws of its own nature, to ever higher and more remote conditions [greater abstractions]. But it [human reason] quickly discovers that, in this way, its labours must remain ever incomplete, because new questions never cease to present themselves; and thus it [human reason] finds itself compelled to have recourse to principles which transcend the region of experience, while they are regarded by common sense without distrust. MM: "But when it perceives that in this way its work remains for ever incomplete, because the questions never cease, it finds itself constrained to take refuge in principles which exceed every possible experimental application, and [yet] nevertheless seem so unobjectionable that even ordinary common sense agrees with them." VG: Reason discovers that the questions never end; in that, we can ask why x occurs, but then, with an answer, we ask why that occurs. There is no end to this sequence, which is unsatisfying. Perceiving this endless chain, reason asks if there is some sort of higher cause or first cause as unifying element. This is the situation that reason is driven into as it seeks to fulfill its task of bringing order and sense to the world. It [reason] thus [disconnected from common experience] falls into confusion and contradictions, from which it [reason] conjectures the presence of latent errors, which, however, it [reason, within its own domain] is unable to discover, because the principles it employs, transcending the limits of experience, cannot be tested by that criterion [by experience]. PG: “… it can indeed surmise that it must somewhere be proceeding on the ground of hidden errors; but it cannot discover them, for the principles on which it is proceeding, since they surpass the bounds of all experience, no longer recognize any touchstone of experience.” Reason suspects that it's got something wrong but can't figure out what's wrong because the principles it's using both transcend and cannot be tested by experience. VG: Reason then feels compelled to make a jump into an area unsupported by experience, which means there can be no knowledge by way of experience, and this is cause for much error, and the sordid state of philosophy today. The arena of these endless contests is called Metaphysics. VG: For Kant the real problem of metaphysics starts when reason discovers its own finitude; that, it’s not omniscient God after all, that reason cannot fulfill its task, and that it will never complete its task, because there will always be something outside its grasp and ken – and, at that moment, when reason tries to transcend itself and rise to a higher level of knowing to acquire full knowledge, that’s when reason goes wrong. This is Kant’s overview as to why metaphysics is a mess. The second half of the “Critique,” the “dialectic,” is where Kant particularly addresses this issue. Time was, when she [reason] was the queen of all the sciences; and, if we take the will for the deed, she certainly deserves, so far as regards the high importance of her object-matter [that is, creating rational order], this title of honour. Now, it is the fashion of the time to heap contempt and scorn upon her [reason]; and the matron mourns, forlorn and forsaken, like Hecuba: "Hecuba, in Greek legend, the principal wife of the Trojan king Priam, mother of Hector, and daughter, according to some accounts, of the Phrygian king Dymas. When Troy was captured by the Greeks, Hecuba was taken prisoner. Her fate was told in various ways, most of which connected her with the promontory Cynossema (Dog’s Monument) on the Hellespont. According to Euripides (in the Hecuba), her youngest son, Polydorus, had been placed under the care of Polymestor, king of Thrace. When the Greeks reached the Thracian Chersonese on their way home, she discovered that her son had been murdered and in revenge put out the eyes of Polymestor and murdered his two sons. Later, she was turned into a dog, and her grave became a mark for ships." Modo maxima rerum, “But late on the pinnacle of fame, At first, her [reason's] government, under the administration of the dogmatists, was an absolute despotism. But, as the legislative [of the dogmatists] continued to show traces of the ancient barbaric rule, her empire gradually broke up, and intestine [internal] wars introduced the reign of anarchy; while the sceptics, like nomadic tribes, who hate a permanent habitation and settled mode of living, attacked from time to time those who had organized themselves into civil communities. But their number was, very happily, small; and thus they could not entirely put a stop to the exertions of those who persisted in raising new edifices, although on no settled or uniform plan. In times past despotic rulership put forward their version of reason but this was mere autocratism, not reason. Internal wars means, there were many competing despots each with their own version of reason Philosophy and reason survived by those who lived in "civil communities," that is, those who were not despotic, but these civil ones were attacked by sceptics, those who did not believe that a reasoned way could produce truth. But these sceptics could not stop philosophy and reason "who persisted in raising new edifices," creating new philosophical ideas and structures, although these new philosophical ideas arose haphazardly with no underlying plan. Kant is intimating that he can give unity to philosophical ideas In recent times the hope dawned upon us of seeing those disputes settled, and the legitimacy of her [reason's] claims established by a kind of physiology of the human understanding—that of the celebrated Locke. But it was found that—although it was affirmed that this so-called queen could not refer her descent to any higher source than that of common experience, a circumstance which necessarily brought suspicion on her claims—as this genealogy was incorrect, she persisted in the advancement of her claims to sovereignty. Thus metaphysics necessarily fell back into the antiquated and rotten constitution of dogmatism, and again became obnoxious to the contempt from which efforts had been made to save it. At present, as all methods, according to the general persuasion, have been tried in vain, there reigns nought but weariness and complete indifferentism—the mother of chaos and night in the scientific world, but at the same time the source of, or at least the prelude to, the re-creation and reinstallation of a science, when it has fallen into confusion, obscurity, and disuse from ill-directed effort. VG: "indifferentism": because of the chaos in metaphysics, with no ability to gain real answers to important questions, people are dismissive of it with "bah, metaphysics - useless, whatever!" All of this is unfortunate, says Kant, because we cannot afford to be indifferent to the big questions of life, and are required to ask: is there a God, a soul, are we free, etc. It is in the nature of reason itself to ask these questions and it does no good to attempt a dismissiveness, because reason will not stand down from the questions. John Locke had recently tried to unite the disputations concerning reason by offering a kind of anatomy of human understanding. "John Locke (1632-1704) was among the most famous philosophers and political theorists of the 17th century. He is often regarded as the founder of a school of thought known as British Empiricism, and he made foundational contributions to modern theories of limited, liberal government. He was also influential in the areas of theology, religious toleration, and educational theory. In his most important work, the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke set out to offer an analysis of the human mind and its acquisition of knowledge. He offered an empiricist theory according to which we acquire ideas through our experience of the world. The mind is then able to examine, compare, and combine these ideas in numerous different ways. Knowledge consists of a special kind of relationship between different ideas. Locke’s emphasis on the philosophical examination of the human mind as a preliminary to the philosophical investigation of the world and its contents represented a new approach to philosophy, one which quickly gained a number of converts, especially in Great Britain." It was claimed that reason could, in her geneology, point to no higher source than that of experience, but this is incorrect, and the notion was criticized, but, even so, reason still maintained its claim to dominion by way of experience. This reliance on experience as primary foundation of reason has, in Kant's day, made science into a mess, but at least this confusion might serve as prelude to a new day in science For it is in reality vain to profess indifference in regard to such inquiries, the object of which cannot be indifferent to humanity. Besides, these pretended indifferentists, however much they may try to disguise themselves by the assumption of a popular style and by changes on the language of the schools, unavoidably fall into metaphysical declarations and propositions, which they profess to regard with so much contempt. At the same time, this indifference, which has arisen in the world of science, and which relates to that kind of knowledge which we should wish to see destroyed the last, is a phenomenon that well deserves our attention and reflection. It is plainly not the effect of the levity, but of the matured judgement[1] of the age, which refuses to be any longer entertained with illusory knowledge. It is, in fact, a call to reason, again to undertake the most laborious of all tasks—that of self-examination, and to establish a tribunal, which may secure it in its well-grounded claims, while it pronounces against all baseless assumptions and pretensions, not in an arbitrary manner, but according to its own eternal and unchangeable laws. This tribunal is nothing less than the Critical Investigation of Pure Reason. "not the effect of the levity, but of the matured judgement": MM: "It is clearly the result, not of the carelessness, but of the matured judgment* of our age, which will no longer rest satisfied with the mere appearance of knowledge. It is, at the same time, a powerful appeal to reason to undertake anew the most difficult of its duties, namely, self-knowledge, and to institute a court of appeal which should protect the just rights of reason, but dismiss all groundless claims, and should do this not by means of irresponsible decrees, but according to the eternal and unalterable laws of reason. This court of appeal is no other than the Critique of Pure Reason." "self-examination"; or the MM translation, "self-knowledge": reason takes upon itself the most difficult ("most laborious") of all tasks, that of coming to know itself. VG says that "The Critique" features reason's attempt to gain self-knowledge. It is reason trying to understand itself. Kant is not talking about a psychological investigation of the mind. Reason studying itself is a pure project; "pure" for Kant means not linked to experience. And this is important to Kant as his investigation of reason is not about psychological experiments of the mind. What Kant is setting out to do is to say that reason, understanding itself, will solve the basic problem of metaphysics. And this basic problem is that we don't realize why we get into trouble; we follow the natural inclinations of reason but these drive reason beyond the bounds of its own abilities, beyond where it can actually gain knowledge. And so it will be reason's self-knowledge that will keep us from that kind of trouble. “unavoidably fall into metaphysical declarations and propositions, which they profess to regard with so much contempt”: I've known religionists, so contemptuous of the domain of philosophy – as they felt threatened by this competition – who, in their diatribes “with so much contempt” against philosophy they “unavoidably fall into” their own professions of religious philosophical precept. "knowledge... destroyed at last": this knowledge is related to the "indifferentists" who heap contempt upon philosophy and well-ordered reason, their corrupt version of so-called knowledge must be done away with. It is "illusory knowledge," not knowledge at all, but mere prejudice, "baseless assumptions and pretensions". As opposed to all this illusion and self-deception, the present philosophical chaos relating to definitions of corrupted forms of knowledge and reason should be viewed as a "call to reason ... and self-examination." All of this becomes the basis of the book. [1] We very often hear complaints of the shallowness of the present age, and of the decay of profound science. But I do not think that those which rest upon a secure foundation, such as mathematics, physical science, etc., in the least deserve this reproach, but that they rather maintain their ancient fame, and in the latter case, indeed, far surpass it. The same would be the case with the other kinds of cognition, if their principles were but firmly established. In the absence of this security, indifference, doubt, and finally, severe criticism are rather signs of a profound habit of thought. Our age is the age of criticism, to which everything must be subjected. The sacredness of religion, and the authority of legislation, are by many regarded as grounds of exemption from the examination of this tribunal. But, if they are exempted, they become the subjects of just suspicion, and cannot lay claim to sincere respect, which reason accords only to that which has stood the test of a free and public examination. "Our age is the age of criticism": MM: "Our age is, in every sense of the word, the age of criticism, and everything must submit to it. Religion, on the strength of its sanctity, and law, on the strength of its majesty, try to withdraw [exempt] themselves from it; but by so doing they arouse just suspicions, and cannot claim that sincere respect which reason pays to those only who have been able to stand its free and open examination." "firmly established": Kant is saying that some of the sciences or fields of knowledge, including philosophy and modes of reason, are not firmly established, but built upon illusory knowledge. “become the subjects of just suspicion”: think of the totalitarians of our day who disingenuously claim that certain information, which, in truth, is damaging to the totalitarians’ cause, is “misinformation” and, therefore they say, must be censored. But this “book burning” mentality does nothing but arouse suspicion of a philosophical position so weak that it cannot withstand public scrutiny. "signs of a profound habit": because much of today's knowledge does not rest upon a firm foundation, those who doubt and call into question are actually exhibiting a "profound" reaction, as there's much to be dissatisfied with. I do not mean by this a criticism of books and systems, but a critical inquiry into the faculty of reason, with reference to the cognitions to which it strives to attain without the aid of experience; in other words, the solution of the question regarding the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics, and the determination of the origin, as well as of the extent and limits of this science. All this must be done on the basis of principles. Kant's book is not so much a review of other books and systems. The book is about a "critical inquiry into the faculty of reason" - but, with special emphasis on reason's strivings for knowledge "without the aid of experience." Because the investigations will be done without recourse to sensory experience, he proposes the inquiry will be conducted "on the basis of principles." I see this to be like flying a plane without visual aid but only instrumentation. This path—the only one now remaining—has been entered upon by me; and I flatter myself that I have, in this way, discovered the cause of—and consequently the mode of removing—all the errors which have hitherto set reason at variance with itself, in the sphere of non-empirical thought. I have not returned an evasive answer to the questions of reason, by alleging the inability and limitation of the faculties of the mind; I have, on the contrary, examined them completely in the light of principles, and, after having discovered the cause of the doubts and contradictions into which reason fell, have solved them to its [reason's] perfect satisfaction. It is true, these questions have not been solved as dogmatism, in its vain fancies and desires, had expected; for it [dogmatism] can only be satisfied by the exercise of magical arts, and of these I have no knowledge. But neither do these [higher, abstract questions] come within the compass of our mental powers; and it was the duty of philosophy to destroy the illusions which had their origin in misconceptions, whatever darling hopes and valued expectations may be ruined by its explanations. My chief aim in this work has been thoroughness; and I make bold to say that there is not a single metaphysical problem that does not find its solution, or at least the key to its solution, here. Pure reason is a perfect unity; and therefore, if the principle presented by it prove to be insufficient for the solution of even a single one of those questions to which the very nature of reason gives birth, we must reject it, as we could not be perfectly certain of its sufficiency in the case of the others. "This path—the only one now remaining": this path is the task of reforming the platonic realm, the higher-order abstract reasonings, without aid of sensory experience; reason falls into confusion when divorced from sensory experience; Kant sees it his job to attempt to create order by means of new principles “errors which have hitherto set reason at variance with itself”: Kant had said that reason gets into trouble when it becomes more and more abstract, more detached from sensory experience Aristotle would say that reason which is not connected to the senses is not reason properly construed, but Kant departs from Aristotle here, Kant says that reason can very much operate in a realm transcending the five senses In common parlance, we uphold the Aristotelian view, we say, “it makes sense,” that is, “reason conforms to sensory experience,” and if it does not, we say “it doesn’t make sense”; if “it’s nonsense,” this means that “there’s no information here that is supported by the five senses.” But Kant is redefining reason here. “the sphere of non-empirical thought”: empiricism is related to observation, in other words, reason can operate in the sphere of non-sensory perception, but it gets into trouble there if unguided by certain "principles" "have not been solved as dogmatism, in its vain fancies and desires ... for it [dogmatism] can only be satisfied by the exercise of magical arts": Kant has stated that he’s found the solution to the problems of reason, even to reason’s “perfect satisfaction.” Acknowledging this success, Kant cautions that this discovery is not to be categorized as a new dogmatism – here, doubtless, he’s referring to the “infallible” answers of the church which seal their dogmatism in “magical arts,” that is, magic words, and magic hand-signs, which, they say, become dispositive to truth acquisition. No, says, Kant, it’s not like that, after all, this is reason we’re talking about here, not strong-arming the mind into submission. “neither do these [higher, abstract questions] come within the compass of our mental powers; and it was the duty of philosophy to destroy the illusions”: earlier, right at the start of the preface, Kant said that the higher abstract questions “transcend every faculty of the mind” and “[reason] falls into this difficulty without any fault of its own.” This being the case, it fell to philosophy to pop bubbles of “illusion”, the “darling hopes” which had been built upon sensory experience but could never find truth in this manner. “not a single metaphysical problem that does not find its solution, or at least the key to its solution, here”: Kant is very bold. He’s not yet explained what his “principles” are – this is only the preface – but, he says, these are so powerful that every metaphysical problem is helped by them. “Pure reason is a perfect unity”, and so if it were possible to find one error, then the whole edifice might come tumbling down While I say this, I think I see upon the countenance of the reader signs of dissatisfaction mingled with contempt, when he hears declarations which sound so boastful and extravagant; and yet they are beyond comparison more moderate than those advanced by the commonest author of the commonest philosophical programme, in which the dogmatist professes to demonstrate the simple nature of the soul, or the necessity of a primal being. Such a dogmatist promises to extend human knowledge beyond the limits of possible experience; while I humbly confess that this is completely beyond my power. Instead of any such attempt, I confine myself to the examination of reason alone and its pure thought; and I do not need to seek far for the sum-total of its cognition, because it has its seat in my own mind. Besides, common logic presents me with a complete and systematic catalogue of all the simple operations of reason; and it is my task to answer the question how far reason can go, without the material presented and the aid furnished by experience. “signs of dissatisfaction mingled with contempt”: Kant says that he will be accused of overweening pride with his claims to have found answers to all metaphysical questions, but, he says, the real proud ones are those who make claims of areas of knowledge of which we have no experience, and yet they claim a great knowledge. These are church dogmatists. “do not need to seek far”: not far because the seat of reason is in my own person and mind, close at hand, and so self-examination is my teacher “the question how far reason can go, without the material presented and the aid furnished by experience”: this is Kant’s great question – how far can reason go without experience So much for the completeness and thoroughness necessary in the execution of the present task. The aims set before us are not arbitrarily proposed, but are imposed upon us by the nature of cognition itself. The above remarks relate to the matter of our critical inquiry. As regards the form, there are two indispensable conditions, which any one who undertakes so difficult a task as that of a critique of pure reason, is bound to fulfil. These conditions are certitude and clearness. As regards certitude, I have fully convinced myself that, in this sphere of thought, opinion is perfectly inadmissible, and that everything which bears the least semblance of an hypothesis must be excluded, as of no value in such discussions. MM: "...in this kind of enquiry it is in no way permissible to propound mere opinions, and that everything looking like a hypothesis is counterband" For it is a necessary condition of every cognition that is to be established upon à priori grounds that it shall be held to be absolutely necessary; much more is this the case with an attempt to determine all pure à priori cognition, and to furnish the standard—and consequently an example—of all apodeictic (philosophical) certitude. PG: "For every cognition that is supposed to be certain a priori proclaims that it wants to be held for absolutely necessary, and even more is this true of a determination of all pure cognitions a priori, which is to be the standard and thus even the example of all apodictic (philosophical) certainty" a priori: "a way of gaining knowledge without appealing to any particular experience(s). This method is used to establish transcendental and logical truths." SP a priori: etymology online: literally ‘from what comes first’ ... Since c. 1840, based on Kant, used more loosely for ‘cognitions which, though they may come to us in experience, have their origin in the nature of the mind, and are independent of experience’ Whether I have succeeded in what I professed to do, it is for the reader to determine; it is the author’s business merely to adduce grounds and reasons, without determining what influence these ought to have on the mind of his judges. But, lest anything he may have said may become the innocent cause of doubt in their minds, or tend to weaken the effect which his arguments might otherwise produce—he may be allowed to point out those passages which may occasion mistrust or difficulty, although these do not concern the main purpose of the present work. He does this solely with the view of removing from the mind of the reader any doubts which might affect his judgement of the work as a whole, and in regard to its ultimate aim. TN: "Whether I have succeeded in what I have undertaken must be left altogether to the reader's judgment; the author's task is solely to adduce grounds, not to speak as to the effect which they should have upon those who are sitting in judgment. But the author, in order that he may not himself, innocently, be the cause of any weakening of his arguments, may be permitted to draw attention to certain passages, which, although merely incidental, may yet occasion some mistrust. Such timely intervention may serve to counteract the influence which even quite undefined doubts as to these minor matters might otherwise exercise upon the reader's attitude in regard to the main issue." MM: "Whether I have fulfilled what I have here undertaken to do, must be left to the judgment of the reader; for it only behoves the author to propound his arguments, and not to determine beforehand the effect which they ought to produce on his judges. But, in order to prevent any unnecessary weakening of those arguments, he may be allowed to point out himself certain passages which, though they refer to collateral objects only, might occasion some mistrust, and thus to counteract in time the influence which the least hesitation of the reader in respect to these minor points might exercise with regard to the principal object." I know no investigations more necessary for a full insight into the nature of the faculty which we call understanding, and at the same time for the determination of the rules and limits of its use, than those undertaken in the second chapter of the “Transcendental Analytic,” under the title of Deduction of the Pure Conceptions of the Understanding; and they have also cost me by far the greatest labour—labour which, I hope, will not remain uncompensated. The view there taken, which goes somewhat deeply into the subject, has two sides. The one relates to the objects of the pure understanding, and is intended to demonstrate and to render comprehensible the objective validity of its à priori conceptions; and it forms for this reason an essential part of the Critique. The other considers the pure understanding itself, its possibility and its powers of cognition—that is, from a subjective point of view; and, although this exposition is of great importance, it does not belong essentially to the main purpose of the work, because the grand question is what and how much can reason and understanding, apart from experience, cognize, and not, how is the faculty of thought itself possible? "pure understanding": to understand before one experiences or "apart from experience." MM: "This enquiry, which rests on a deep foundation, has two sides. The one refers to the objects of the pure understanding, and is intended to show and explain the objective value of its concepts a priori. It is, therefore, of essential importance for my purposes. The other is intended to enquire into the pure understanding itself, its possibility, and the powers of knowledge on which it rests, therefore its subjective character; a subject which, though important for my principal object, yet forms no essential part of it, because my principal problem is and remains, What and how much may understanding (Verstand) and reason (Vernunft) know without all experience? and not, How is the faculty of thought possible?" "the grand question is what and how much can reason and understanding, apart from experience, cognize": Kants restates his major question. TN: "For the chief question is always simply this: what and how much can the understanding and reason know apart from all experience?" As the latter is an inquiry into the cause of a given effect, and has thus in it some semblance of an hypothesis (although, as I shall show on another occasion, this is really not the fact), it would seem that, in the present instance, I had allowed myself to enounce a mere opinion, and that the reader must therefore be at liberty to hold a different opinion. RPW: “What on earth is going on here? This is the section called the subjective deduction, which is the first part of the transcendental deduction in A. The subjective deduction, Kant completely left out of the second edition when he rewrote the deduction. He just left out all the material from the subjective deduction. Because, as he said, it’s subjective, and more like the description of a cause, and therefore it’s somewhat hypothetical. But there’s some part of Kant that knows that this is not true. That, in fact, what he said in the subjective deduction is the essential part of the argument. So, he says, as I shall show later it is not really so, he hedges his bets. Now, fair warning, when I get to that part of The Critique you will discover that I make what is contained in the subjective deduction the key to understanding the entire book. Without that the book is mysterious and incomprehensible and has remained so for Kant commentators for generations. With that section it is finally possible to transform what Kant says into a straightforward argument from premise to conclusion, the conclusion being the validity of the causal maxim. But, Kant is right – it is a description of the way the mind works and in that sense is not just logic but psychology as well. That made Kant nervous but there’s no way around it. So I just flag that passage, tell you that I’m going to come back to it, because when we get to the subjective deduction, you will find that the key concept in Kant’s whole argument, the concept of synthesis, the concept that gives us the phrase synthetic a priori, for example, that concept of synthesis is incomprehensible without the subjective deduction, without the subjective deduction it’s a metaphor and you can’t base a philosophical argument on a metaphor, unless you can cash the metaphor in. In the subjective deduction, Kant cashes the metaphor in and tells us what synthesis is. But it will take us a while to get to that.” But I beg to remind him that, if my subjective deduction does not produce in his mind the conviction of its certitude at which I aimed, the objective deduction, with which alone the present work is properly concerned, is in every respect satisfactory. As regards clearness, the reader has a right to demand, in the first place, discursive or logical clearness, that is, on the basis of conceptions, and, secondly, intuitive or æsthetic clearness, by means of intuitions, that is, by examples or other modes of illustration in concreto. I have done what I could for the first kind of intelligibility. This was essential to my purpose; and it thus became the accidental cause of my inability to do complete justice to the second requirement. I have been almost always at a loss, during the progress of this work, how to settle this question. Examples and illustrations always appeared to me necessary, and, in the first sketch of the Critique, naturally fell into their proper places. But I very soon became aware of the magnitude of my task, and the numerous problems with which I should be engaged; and, as I perceived that this critical investigation would, even if delivered in the driest scholastic manner, be far from being brief, I found it unadvisable to enlarge it still more with examples and explanations, which are necessary only from a popular point of view. I was induced to take this course from the consideration also that the present work is not intended for popular use, that those devoted to science do not require such helps, although they are always acceptable, and that they would have materially interfered with my present purpose. PG: "Finally, as regards clarity, a the reader has a right to demand first discursive (logical) clarity, through concepts, but then also intuitive (aesthetic) clarity, through intuitions, that is, through examples or other illustrations in concreto. I have taken sufficient care for the former. That was essential to my undertaking but was also the contingent cause of the fact that I could not satisfy the second demand, which is less strict but still fair. In the progress of my labor I have been almost constantly undecided how to deal with this matter. Examples and illustrations always appeared necessary to me, and hence actually appeared in their proper place in my first draft. But then I looked at the size of my task and the many objects with which I would have to do, and I became aware that this alone, treated in a dry, merely scholastic manner, would suffice to fill an extensive work; thus I found it inadvisable to swell it further with examples and illustrations, which are necessary only for a popular aim, especially since this work could never be made suitable for popular use, and real experts in this science do not have so much need for things to be made easy for them; although this would always be agreeable, here it could also have brought with it something counter-productive.” Abbé Terrasson remarks with great justice that, if we estimate the size of a work, not from the number of its pages, but from the time which we require to make ourselves master of it, it may be said of many a book—that it would be much shorter, if it were not so short. On the other hand, as regards the comprehensibility of a system of speculative cognition, connected under a single principle, we may say with equal justice: many a book would have been much clearer, if it had not been intended to be so very clear. For explanations and examples, and other helps to intelligibility, aid us in the comprehension of parts, but they distract the attention, dissipate the mental power of the reader, and stand in the way of his forming a clear conception of the whole; as he cannot attain soon enough to a survey of the system, and the colouring and embellishments bestowed upon it prevent his observing its articulation or organization—which is the most important consideration with him, when he comes to judge of its unity and stability. Abbé (Abbot) Terrasson: Wikipedia: "Jean Terrasson (1670-1750), often referred to as the Abbé Terrasson, was a French Catholic priest, author and member of the Académie française." PG: "The Abbe Terrasson says that if the size of a book is measured not by the number of pages but by the time needed to understand it, then it can be said of many a book that it would be much shorter if it were not so short. But on the other hand, if we direct our view toward the intelligibility of a whole of speculative cognition that is wide-ranging and yet is connected in principle,a we could with equal right say that many a book would have been much clearer if it had not been made quite so clear. For the aids to clarity help in the parts but often confuse in the whole, since the reader cannot quickly enough attain a survey of the whole; and all their bright colors paint over and make unrecognizable the articulation or structure of the system, which yet matters most when it comes to judging its unity and soundness." MM: "The Abbé Terrasson writes indeed that, if we measured the greatness of a book, not by the number of its pages, but by the time we require for mastering it, many a book might be said to be much shorter, The reader must naturally have a strong inducement to co-operate with the present author, if he has formed the intention of erecting a complete and solid edifice of metaphysical science, according to the plan now laid before him. Metaphysics, as here represented, is the only science which admits of completion—and with little labour, if it is united, in a short time; so that nothing will be left to future generations except the task of illustrating and applying it didactically. For this science is nothing more than the inventory of all that is given us by pure reason, systematically arranged. Nothing can escape our notice; for what reason produces from itself cannot lie concealed, but must be brought to the light by reason itself, so soon as we have discovered the common principle of the ideas we seek. The perfect unity of this kind of cognitions, which are based upon pure conceptions, and uninfluenced by any empirical element, or any peculiar intuition leading to determinate experience, renders this completeness not only practicable, but also necessary. PR: "For metaphysics is nothing other than the inventory of all our possessions through pure reason, ordered systematically." PG: "It can, as it seems to me, be no small inducement for the reader to unite his effort with that of the author, when he has the prospect of carrying out, according to the outline given above, a great and important piece of work, and that in a complete and lasting way. Now metaphysics, according to the concepts we will give of it here, is the only one of all the sciences that may promise that little but unified effort, and that indeed in a short time, will complete it in such a way that nothing remains to posterity except to adapt it in a didactic manner to its intentions, yet without being able to add to its content in the least. For it is nothing but the inventory of all we possess through pure reason, ordered systematically. Nothing here can escape us, because what reason brings forth entirely out of itself cannot be hidden, but is brought to light by reason itself as soon as reason's common principle has been discovered. The perfect unity of this kind of cognition, and the fact that it arises solely out of pure concepts without any influence that would extend or increase it from experience or even particular intuition, which would lead to a determinate experience, make this unconditioned completeness not only feasible but also necessary." Tecum habita, et nôris quam sit tibi curta supellex. "Live with yourself: get to know how poorly furnished you are." Such a system of pure speculative reason I hope to be able to publish under the title of Metaphysic of Nature[2]. The content of this work (which will not be half so long) will be very much richer than that of the present Critique, which has to discover the sources of this cognition and expose the conditions of its possibility, and at the same time to clear and level a fit foundation for the scientific edifice. In the present work, I look for the patient hearing and the impartiality of a judge; in the other, for the good-will and assistance of a co-labourer. For, however complete the list of principles for this system may be in the Critique, the correctness of the system requires that no deduced conceptions should be absent. These cannot be presented à priori, but must be gradually discovered; and, while the synthesis of conceptions has been fully exhausted in the Critique, it is necessary that, in the proposed work, the same should be the case with their analysis. But this will be rather an amusement than a labour. PG: "Such a system of pure (speculative) reason I hope myself to deliver under the title Metaphysics of Nature, which will be not half so extensive but will be incomparably richer in content than this critique, which had first to display the sources and conditions of its possibility, and needed to clear and level a ground that was completely overgrown. Here I expect from my reader the patience and impartiality of a judge, but there I will expect the cooperative spirit and assistance of a fellow worker; for however completely the principles of the system may be expounded in the critique, the comprehensiveness of the system itself requires also that no derivative concepts should be lacking, which, however, cannot be estimated a priori in one leap, but must be gradually sought out; likewise, just as in the former the whole synthesis of concepts has been exhausted, so in the latter it would be additionally demanded that the same thing should take place in respect of their analysis, which would be easy and more entertainment than labor." [2] In contradistinction to the Metaphysic of Ethics. This work was never published.

|

||

|

|